Just like the advent of social media, the Eurovision Song Contest is meant to be about sharing experiences and bringing people together. Both outlets give people a voice and a chance to interact within communities that previously were unavailable. The displayed diversity of people and the glimpse into other cultures aim to bring about a greater understanding and empathy for each other.

However, somewhere along the line, that message was lost and forgotten. Rotterdam’s Eurovision Song Contest has been punctuated by stories of hate. Whilst discrimination and messages of hate have always played some small part in the Contest lead-up, it perhaps has never been as more acknowledged and prominently displayed as an issue as this year.

Wiggling the Middle Finger

Beyond the impact of Covid creating a socially isolated world where we have become more insular and ever more present online, this year’s Contest is also set to a cultural backdrop of the Black Lives Matter movement, human rights violations by political parties, disputes over borders, disparity of wealth, and a worldwide increase in violence against women. A few of these themes are echoed by lyrics and presentations of this year, but the one song that truly shines a light on the overarching issue of hate is that of entrant Jendrik.

Despite the 3-minute clip being a sensory overload of colour and glitter, with the jangly performance delivered by a seemingly Red-Bull fuelled young German armed with a bejeweled ukelele, the messages ring loud and clear on ‘I Don’t Feel Hate’. Here we see our actors representing various aspects of society that are regularly targeted – the LGBQTI community, the overweight, women, as well as differing nationalities, religions, abilities, and socio-economic classes. The storyline makes pointed statements of how discrimination is enacted, whilst the lyrics encourage people to recognize and not spread hate further. The release of the song however – in a sad yet predictable way – sparked the very opposite reaction.

Many people reacted harshly to Germany’s new entry which was selected by an internal panel of judges. Jendrik was trolled by keyboard warriors, called a ‘f*ggot’, became the recipient of direct messages featuring an overzealous analysis on his entry, and the target of a widespread meme declaring ‘Sorry Germany, nul points’.

Did you know? pic.twitter.com/k9EaB619fz

— Jendrik (@Jendrikkkk) April 10, 2021

Whilst initially he would respond on his social media with reference back to his lyrics that he ‘wouldn’t wiggle the middle finger back to you’, the experiences culminated in Jendrik launching a week of coverage that further addressed the themes introduced to us in his film clip. Each day focused on a form of hate where he asked people to share their own experiences, interviewed victims but also featured key service providers in the field of mental health and social support. Yes, it may have been part of a well-planned media campaign, but it also served as a much-needed spotlight on the issue of hate.

Mixed & Missed Messaging

In an ideal world, the coverage Jendrik provided on the themes would have forced the Eurovision media and community it was largely aimed at to at least consider a modification of behaviours. But we also understand that there has been, not helped by the instant nature of social media, a normalisation to publish one’s thoughts and value given to opinion over fact, coupled now with younger generations who are actively driven to share their feelings.

One story that played out early on in the 2021 season is that of North Macedonian entry Vasil Garvanliev. On the release of his film clip for ‘Here I Stand’, he was wrongfully perceived by the public as insulting Macedonian identity due to a piece of art featured that was wrongly interpreted as the Bulgarian Flag, thus promoting Bulgarian nationalism and his ethnic origins as a dual citizen.

It quickly escalated with the local broadcaster examining whether his participation should continue. The fan community started to post online in support of his case to remain as the chosen entry. Fortunately, he was given the green light by the broadcaster, but his clip has been modified to remove the offending image, and locally he remains a controversial choice as he openly revealed his sexuality in the media. He continues to be subject to cyberbullying, and once again, it has been fandom that led the way in lifting his spirits and supporting him – something which he has openly acknowledged on his social media accounts.

But as the community rallied around Vasil, at the same time, many of the same community lashed out at Norwegian entry Tix after decisively winning the national selection process Melodi Grand-Prix over fandom-favourites Keiino.

The name and stage identity of Tix was spawned directly from childhood playground taunts suffered due to his Tourettes Syndrome, and this storyline of bullying has been prominent within his Eurovision media campaign with the release of a documentary and also central in the film clip for his entry ‘Fallen Angel’. But even despite coming through that trauma earlier in his life, he still found the criticism following his win an overwhelming experience, leading him to remove himself from the social media storm and setting his accounts on private or no comment.

Another artist who is not afraid to shy away from speaking freely on dealing with bullying is Russian entry, Manizha. Over the course of her career, she has been targeted for her beliefs – working on social projects regarding domestic violence and the LGBQTI community.

Her inclusion in this year’s hastily organised three-act national final courted much criticism; then winning with ‘Russian Woman’, a feminist warcry attacking stereotypes. Following her selection, she received death threats both on the lyrics but also her heritage as a Tajikistan refugee living in Russia. Nevertheless, she continues to call the behaviours out openly in media and remains faithful to her aim to shine a light on women’s empowerment on the international stage.

The perception of what is viewed as ‘acceptable’ and ‘belongs’ on the Eurovision stage remains the biggest reason for targeting artists at Eurovision. Following Sweden’s first rehearsal on the Ahoy stage, the contest’s official channels saw an influx of racist comments questioning Tusse’s right to participate in the contest for Sweden. Broadcaster SVT and the Head of Delegation Lotta Furebäck issued a statement to press in response clearly stating that “racism in all it’s forms is completely reprehensible… (Tusse’s entry) ‘Voices’ is largely about being accepted and dealing with exclusion in all forms, something we hope will become clear when he now shows himself to an even larger audience”.

Instagram: @eurofanjulian

Home soil competitor Jeangu Macrooy also found himself subjected to racism on the release of his song ‘Birth of A New Age’. The track was written under the influence of the Black Lives Matter movement, speaking of oppression and resilience whilst celebrating his Surinamese heritage and the Sranantongo language. Many in the Netherlands, including members of official media, asked how it could represent the nation given its themes, and the sentence ‘yu no man broko mi ‘ (translation: you will not break me), became a national joke due to a misheard lyric featuring broccoli.

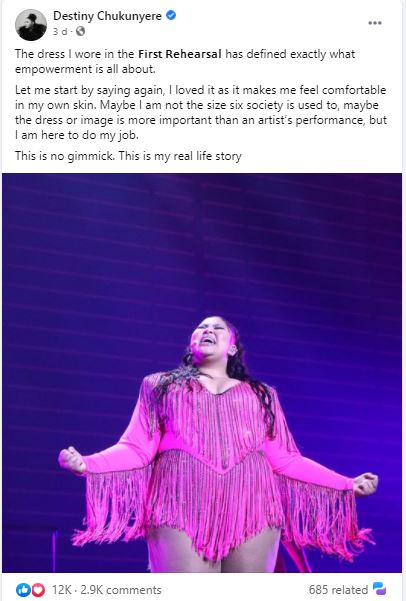

And the most recent example questioning ‘what is acceptable’ took place over the course of this past week of rehearsals with the body shaming of pre-Contest favourite Destiny from Malta. Upon the image release of her planned competition costume, she found herself criticised for wearing a figure-hugging pink costume that was inspired both by her idol Lizzo, and the Charleston-music featured in her entry ‘Je Ma Casse’. At the kinder end of these comments, people called it ‘too revealing’, ‘unflattering’, ‘garish’, ‘tacky’ and a ‘wardrobe disfunction’ – and at the other end – taunts about her weight. Destiny addressed the comments head on both on her social media:

facebook.com/destiny.artist

Neverthless, the social media reaction storm that she bore forced the delegation to adjust their original costuming plans.

The most alarming thing of all of the above examples is that a lot of what we are seeing play out is now directly caused by people within the fandom. On any given chat within the online press centre, everyone is very keen to chip in with comments about what they are watching, and as part of that you will witness posts featuring negative and quite personal statements about the artists as they perform. Within the first 24 hours of rehearsals starting, the EBU Media Team took the liberty to email the following:

“We are really pleased with the engagement in the platform but kindly request that, when watching rehearsals, all journalists respect the values of the Eurovision Song Contest and treat artists with respect… Please bear in mind that members of each delegation are also accessing this tool.”

Whilst there is no official moderation of what one can say on the media chat channels, nor the website and Eurovision social media accounts within the public domain, we need to really examine what purpose they serve and what benefit there is of adding our voice to those outlets.

Critique vs Bullying – The Difference In How It Is Framed

There is constructive feedback, which is designed to help someone improve. It’s clear, to the point, and easy to put into action. Comparatively, negative feedback is designed to discredit, demean, humiliate or cause harm to someone’s reputation.

Any time we provide feedback with the goal of getting someone to better meet our needs, rather than being responsive to theirs, it’s unlikely to prompt the desired outcome. Feedback is not meant to be a channel to vent a string of criticisms or launch a personal attack against someone.

One of the frequent excuses used to downplay the serious nature of what occurs is the idea that somehow these artists chose to come to a competition, and thus ‘need to deal’ with criticism and feedback including the negativity. Yes, they will naturally attract a lot of attention, but they are also human – feeling the same emotions we do.

Criticizing someone for something they can’t change and then walking away makes them feel helpless. Nor does anyone want to hear someone, or a community of people, go on and on about their shortcomings—even in a very polite tone.

When the action or comment is a repeated and unwanted behaviour used to exploit someone and has the ability to affect a person’s physical and mental health that is, plain and simple, bullying.

How Can Our Community Be Better At The Contest?

There is an easy question to ask oneself before you set your fingers to the keyboard – ‘Would I actually say this to someone’s face?’

This is a self-questioning process that ESC Insight has put in place over the last few years; we learned from past mistakes and will gladly own up to where we may have crossed the line. We removed our opinions section within our Guidebook because we didn’t see the value in it, and it’s also a key reason why we don’t typically go out live with our thoughts. Every article we publish has at least two sets of eyes on it. The questions we ask ourselves at the end of every podcast recording are “Is everyone happy with what was discussed (and how our words were framed)? Do we need to edit, or do we want a re-take (to say something in a better way)?”. We are mindful not only that we are going public but, that the words that we use matter.

I grew up with the mantra ‘if you don’t have something nice to say, don’t say anything at all’ constantly repeated by my parents. Negativity should hold no value here, especially considering the framework on which the Song Contest was built. As fans, we have a really valuable role to play in upholding and even spreading the message of acceptance and inclusion that Eurovision espouses.

So, if you see someone bullying, call it out.

If you are caught out, or recognize you are part of the problem, make amends. Make it your purpose to reach out, learn more and empathize.

We don’t feel hate, we just feel sorry that in 2021, with 65 years of Eurovision shows under the EBU belt, this article even has a place in the overall discussion of our beloved contest.

I’ve seen quite a number of these incidents lately:

1. I remember feeling really when I read a comment online from someone opining about what they think of a certain song and they said they dislike it because of the way the performer sings even though it’s a facet of that act’s musical heritage, likewise any artists they are in the mood to insult because of the way they perform, whether just pulling off a falsetto, their creativity, a simple belting out or otherwise. It’s no longer a valid criticism once try to attack the performer’s characteristics and capabilities and sounding extremely dismissive over-all.

2. And of course, a targeted set of tweets coming from a section of the fandom showing their utterly dislike towards one particular artist whenever their name comes around on Twitter and Instagram. They crossed the line when they made 9/11 jokes with utter disregard of the significance of a serious subject they’re passing of a “silly humor”.

While every person should and is responsible for what he/she say, you can’t ignore the rol of social media itself in the whole discussion.

There is no way around it. Social media platforms are not doing much against online hate, body shaming or online abuse.

Why? because that’s what attract people and that’s what keep people online.Social platforms want to keep you active online, as this is part of their business model. Social media platforms are currently not being held responsible for anything published there, as they put it:they only provide a service. In their eyes there is no reason for them to take any action against hate, body shaming or any kind of abuse.

Just think about how quiet the world became , when Donald Trum has been banned from twitter. Maybe, if social media platforms will take responsibility over the content on their platforms, we get a safer online environment.

On a personal note: I am not on any social platform, never have been. A decision I took a long time ago, for many reasons. I am not feeling I miss anything while not there and right now, considering the current atmosphere there, I am glad I am not there.

If you’re an artist putting yourself forward for Adult Eurovision you shouldn’t, as in life, have to put up with racist, sexist or homophobic insults. But if you wear a dodgy costume (Trintje) hit a bum note (Manel), are guilty of ‘dad-dancing’ (Gjon) or your song is a 3 minute synthetic cheesefest (Vasil) you should expect critical and even mocking comment from the media and the fans.

That’s just the way it goes in the entertainment business. It can’t all be adulation. As an artist you will face plenty of criticism, not all of it constructive and some of it unkind. It will hurt but you’ve got to learn to deal with it rather than expecting the media and public to morph into angels.

With that in mind, ESC Insight can we please have some ‘opinion’ back in next year’s guidebook?

@eurojock – I don’t think we are talking about respectful criticism here but about people who felt the need to shame one participant just because she wore a costume they didn’t think it suited her. And I am sure there are other examples where participants were treated bad just because of their sexual preference. That kind of language shouldn’t be tolerated or accepted.

Excellent article, Sharleen 👍👏👏

Thanks Sharleen – a great article. It’s a shame it has to be written though. I appreciate all the efforts you and the team have gone through in making sure lines aren’t crossed.

Sadly there are many people who don’t respect others in the ESC-fan community. I often discuss on FB. Many people don’t respect other taste in music. Some gay fans are very chauvenistic and think ESC “belong to” them alone, and look down on straight fans. Some people are toxic to other nations etc. I like the German message….we should remember it

So it has come to my attention that NRK’s preview show, Address Rotterdam, have mocked the inspiration behind Blas Canto’s song, which is his family members who passed away last year. That is a line they never should have crossed. 🙁

Do people consider the scandal of Damiano supposedly snorting cocaine to be an issue with bullying? I didn’t even notice the clip and the second time around I did. It just looked like he had his head down he could of being doing anything. Yet someone (probably an overly keen fan sour about a poor result) posted on social media and caused all this rukus. Shameful behaviour really.

Roo, from my own viewpoint, it is a form of bullying.

What I saw was a piling on in the main by fans who were disappointed with the result and the loss of their own favourites. Biggest issue was that many forgot the idea that one should be ‘innocent until proven guilty’. And of course, mainstream media willing to propel the ‘fake news’ for a sensational headline across the world, overshadowing what should have been the focus – the first notable and cultural celebration in the past 16 months because of covid.

Given that it’s been proven not the case, I would like to see some apologies made, and I think it’s fair that EBU and the band’s management pursue the matter further as it bought both into disrepute.