The Eurovision Song Contest is a standalone contest. Junior Eurovision is a standalone contest. What if we were to combine the two shows into a single contest to find the ultimate winner? I don’t mean that we should have a single contest with 42 performances lasting six and a half hour a night over three weeks… that’s Sanremo. But what if we considered how different countries were doing by aggregating the results from both November and May?

The idea might sound ridiculous at first. If we were to do so, we could get a sense of how different country’s broadcasters are doing across the board. Are there some broadcasters that had particularly good years? Are there countries doing brilliantly well in one Contest and ending up towards the bottom of the table in another?

More to the point, if a country does well in Junior Eurovision in November, does that bode well for how they might end up doing in May?

It Might Be Silly But There Will be Rules

First, we need to acknowledge that not every delegation that sends performances to Eurovision is doing the same for Junior Eurovision. This weekend’s broadcast from Nice won’t include anyone from any of the countries who were in the top three of the Song Contest in Liverpool. In our ranking combining the two contests, an entry into the junior edition is mandatory.

Second—and this might seem obvious—not every entry in Eurovision successfully qualifies for the Grand Final. In 2022, Mariam Bigvava took Georgia to the bronze medal position in Junior, but Circus Mircus received the fewest points in the second Semi Final in Turin six months earlier. Only nations who qualified for the Grand Final are going to make their way to our joint ranking.

Finally, we should acknowledge one of the consequences of the smaller number of countries involved in Junior Eurovision: when there are fewer juries and televotes, there are fewer points on offer. The way we’re going to deal with this is as follows:

- We start with just the countries that were in both Junior Eurovision and the Grand Final of the Eurovision Song Contest, and look at the total number of points awarded just to those countries in each contest.

- For each country, we take the points that they received and express that as a percentage of the overall number of points received by our set of countries.

- We take an average of those two percentages. Whoever’s highest is winning!

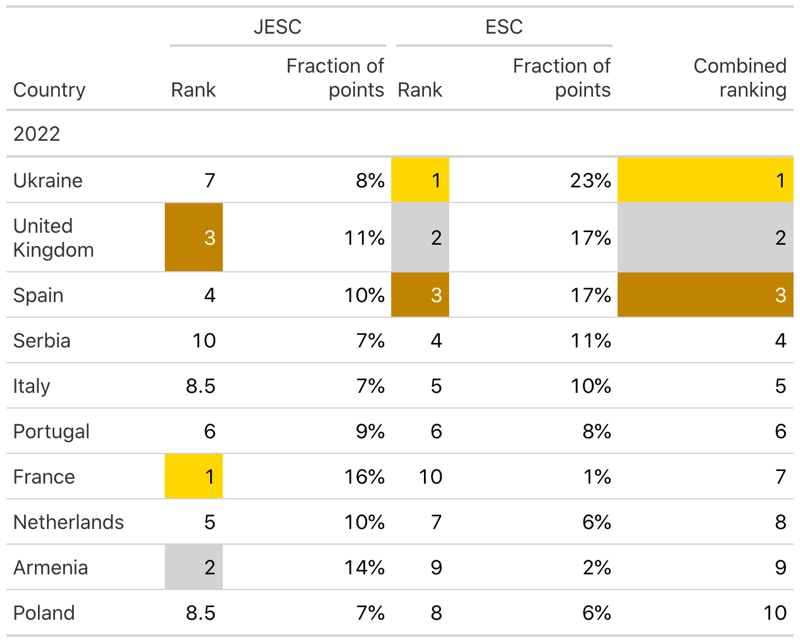

So, who would have won our Combined Song Contest in 2022? Let’s make a quick league table.

Combined JESC and ESC scores in league table format (table: Mark Taylor)

The joint winner in 2022 would have been Ukraine: Kalush Orchestra absolutely dominant in Turin, with the largest televote score in history. Zlata Dziunka may have only been mid-table in Junior Eurovision, but her overall share of the November points was sufficient for Ukraine to remain in the top spot overall.

Having come second in Turin and third in Yerevan, the UK takes the overall silver medal. This consistency is echoed by Spain, who were a position behind the UK in both Contests.

Towards the other end of the table, France may have been the winners in Yerevan, but their relatively small share of the points in Turin means that they come seventh out of ten overall; it’s a similar story for junior silver-medallists Armenia, who are in the penultimate place overall.

Historical Wins And Victories

How does this look when we go a bit further back? This table tells a story of consistency: the country in first place overall did spectacularly well in one contest and mid-table in the other, while the remainder of the podium is filled out by countries doing consistently well, suggesting that doing well in May’s Grand Final often predicts doing well in Junior Eurovision six months later.

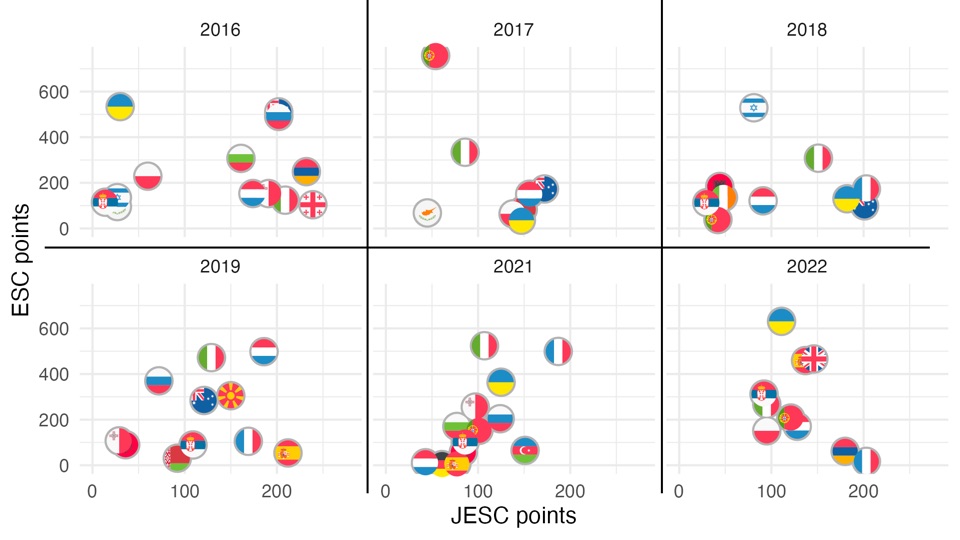

Let’s take a look at the points received across the Contests since 2016. Scores from JESC are along the x-axis, while scores from ESC scores are on the y-axis. The closer you are to the top right, the better your combined performance.

Combined JESC and ESC scores over multiple years (table: Mark Taylor).

When we look at it this way, the story changes. Starting with 2022, we can see that the UK and Spain’s third and fourth places in JESC were some distance behind the top two countries: Spain was, in fact, closer to Serbia (last place in Junior among the countries who qualified for the Eurovision grand final) than to eventual winners France. Taking this series together, the overall trend is negative: for 2022, countries that received more points in one Contest received fewer points in the other.

That isn’t true every year. Going back to 2021, France did brilliantly well in both contests: top-ranked in JESC among our pool of countries, and second place in ESC. While there are a couple of outliers – Måneskin may have won in Rotterdam but Elisabetta Lizza was towards the bottom end in Yerevan, while the opposite is the case for Azerbaijan – for 2021, the trend is that countries who did well in one Contest did well in the other. Further back in 2019, the pattern is positive again, but only weakly.

But across the six years, there’s just no pattern at all. 2017 has the strongest negative relationship of all, driven heavily by Portugal: Salvador Sobral’s highest-ever score was in no way matched in the junior contest; in 2018, there’s no relationship in either direction.

Since 2016, the average correlation between scores in the two contests is 0.06, which statisticians would describe as “basically no relationship”. If we pair up junior editions from the year before to match up with Eurovision seasons rather than calendar years ( for example, pairing Yerevan 2022 with Liverpool 2023) it’s even closer to zero, at 0.03. So it’s not as if performing well in Junior Eurovision means that a country can be more confident about how its delegation will be doing six months later.

Stand On Your Own Beside The Family

The Junior Eurovision Song Contes is its own contest. A country that does well in Junior Eurovision might do well in May’s Eurovision Grand Final, or it might not. That doesn’t mean that Junior Eurovision isn’t worth engaging with; it’s just important to be realistic about what a great performance might entail further down the line.

At the same time, a country that does well in both Contests can feel happy and proud of its achievements.