439 points. ‘Douze points’ from all but eleven nations. The 4th place awarded by Serbia the lowest score received.

This is the reality that befell the Ukrainian song ‘Stefania’ in Turin this past May. Scoring a whopping 63 points more from televoting than previous record holder Salvador Sobral, and 200 points more than second place Moldova, the landslide that Kalush Orchestra received I say with confidence will never again be repeated in our lifetime.

And yet this is a Eurovision win that for many in the community will constantly have an asterisk at the side of the scoreboard. The victory of Ukraine this year can not be disassociated from the Russian invasion that began in February. Without getting too deep, regardless of how much voters loved ‘Stefania’ or not, voting for Ukraine this year meant so much more than just the three minutes on stage.

It meant solidarity.

The world in December 2022 is no nicer. The invasion of Russia on Ukrainian territory continues and the bloody conflict shows no signs of ending. Millions of Ukrainians have fled the nation and escaped across Europe, with the millions left inside threatened by a winter blighted by blackouts and freezing temperatures, never mind the potential for missile strikes on a daily basis. Vidbir, the Ukrainian national selection for Eurovision, is being held deep within the depths of the Kyiv metro system so it can run without disturbance from any conflict at ground level.

There is no reason why any sympathy Europe had with Ukraine in May will be any less seven months later. I assume I’m not the only one that assumes this year’s Junior Eurovision result will quite simply be a case of déjà vu on the final scoreboard.

The Running Order Nobody Would Dare

The running order for Junior Eurovision 2022 has put the question of will Ukraine win the Contest firmly on the lips of all the press I have spoken to in Yerevan. The running order at Junior is partly decided by a random draw and partly by producers. As fate would have it Ukraine randomly drew the final slot in the show.

We in the Eurovision community understand that later draws are generally beneficial, but modern Junior Eurovision history suggests this can be a powerful move. Three of the last six winners have won Junior Eurovision singing in the final spot.

Add to this the fact that randomly drawn before Ukraine is the crowd-pleasing host country track that will get the audience bouncing and you couldn’t ask for any better build-up to a potential winning track. Now we noted when the running order was revealed that these 40 seconds between Armenia and Ukraine performing are particularly heavy in the current geopolitical climate, but nevertheless the ending couldn’t be more dramatic if it tried.

No producer would dare to end Junior Eurovision in this way. Random fate has made the question of the day not just can Ukraine win again, but what can stop them?

The Junior Eurovision Difference

Junior Eurovision may possess a similar-looking voting system to the Eurovision Song Contest for the casual viewer, but underneath it works in significantly differently. While this show is half jury/half public vote, how those points are created in this show isn’t the same as in the contest in May. While the juries are still five people large from each broadcaster, two of those jury members are between the age of 10 to 15. The public vote is also made from an online vote, rather than a televote that the Eurovision Song Contest uses.

One thing that can be investigated here is the importance of being seen to support Ukraine. As we learnt through the disqualification of six juries in this year’s Eurovision Song Contest, the broadcasters who lost the opportunity to present their true points in May felt strongly that they should have had the ability to present a score from that nation. Does that jury vote, the one that is seen as we jump across to different countries each 40 seconds, feel a Ukraine bias?

Given the way the world is today, a possible hypothesis is that Ukraine would benefit from this presenteeism. Do jurors want to ensure Ukraine is being seen to receive points from the jurors taking part in the voting process?

There is a way to look at the 2022 Eurovision Song Contest to observe this. If one looks at the points that Ukraine received from juries in the Semi Final to the Grand Final an interesting trend is observed. Ukraine in pure points from juries finished 3rd behind Greece and The Netherlands in that First Semi Final, a considerable 16 points behind Greece in first place. However in the Grand Final Ukraine finished 4th, but a whopping 34 points above Greece and 63 points above The Netherlands.

Now this comparison is not a fair one as in the Grand Final more countries are voting. Yet even if you only include those nations who voted in both the First Semi Final and the Grand Final the same trend appears, although the shift is smaller. Ukraine would have tied with Greece to share second place in the jury ranking, behind the United Kingdom .

| Country |

Points in Semi Final |

Points in Final (from only the same countries as voted in the same Semi Final) |

| Greece | 151 | 104 |

| Netherlands | 142 | 101 |

| Ukraine | 135 | 104 |

| Portugal | 121 | 102 |

| Switzerland | 107 | 55 |

| Armenia | 82 | 37 |

| Norway | 73 | 24 |

| Iceland | 64 | 9 |

| Lithuania | 56 | 29 |

| Moldova | 19 | 14 |

The obvious assumption here is that jurors have ranked Ukraine higher compared to the other songs as the votes changed from the Monday night jury Semi Final production to the Friday night Jury Final. This is the idea of presenteeism I anticipated, that juries would lift up Ukraine to be seen as giving them points.

However, a trend of presenteeism is not as simple as that. If we take the average of all the jurors’ rankings then Ukraine ranked 3rd in both the Semi Final and the Grand Final with barely any ranking variation compared to their competitors.

What does happen though is the standard deviation, how spread out the results are, of these rankings increases wildly for Ukraine, increasing by 84%, more than any of the other 10 qualifiers. On the Saturday night broadcast while Ukraine’s average ranking was roughly similar there were far more extremes in opinion, with some jurors moving their ranking higher and some ranking lower.

It was those higher rankings which helped Ukraine take higher scores at the top of the rankings. In the Semi Final there were eight juries that gave Ukraine between 8 and 12 points. In the Grand Final there were also eight countries that voted in the First Semi Final that voted for Ukraine in their top three, and three of them (Portugal, Slovenia, Croatia) did not have Ukraine in their top three of that Semi Final. That’s because in the Semi Final only 16 jurors had Ukraine in first place, but in the Grand Final, even with more songs to pick from including the final jury top 3, Ukraine received 19 top rankings from those same jurors.

Simple presenteeism, wanting to be seen to give Ukraine points, would have resulted in the average for points to Ukraine to increase. Instead we conclude that only some jurors felt that presenteeism, but that moved Ukraine dramatically up the leaderboard and within reach of the top points, even when their Semi Final results clearly differed.

Conclusion: Ukraine will likely score high from certain countries’ juries, even if the average is quite low. We expect this push Ukraine will perform better than the community expects from juries on the scoreboard.

Yet this preconception of presenteeism might be different as we travel around the continent. Support for Ukraine, certainly as an issue on the Eurovision scoreboard, is not uniform as we go across from Yerevan to the far corners of the continent.

Of the 16 nations that take part in Junior Eurovision this year, 15 of them took part in Turin’s contest (only Kazakhstan is missing). How did those 15 countries vote and did that leave Ukraine in first place?

Yes, but by a far smaller margin that we saw in May. The gap that Ukraine had at the top of the leaderboard was only 19 points in this scenario. If the difference was so tight across all the countries we would have extrapolated a Ukraine victory by 51 points in Turin, rather than the 165 point landslide Ukraine held over the rest we actually witnessed.

| Country | Jury Points from 15 JESC nations | Televote Points from 15 JESC nations | Total Points from 15 JESC nations |

| Ukraine | 52 | 151 | 203 |

| Spain | 95 | 89 | 184 |

| United Kingdom | 102 | 67 | 169 |

| Sweden | 86 | 54 | 140 |

| Moldova | 8 | 106 | 114 |

If anything the nations that will take part in JESC feature those that were most divided on Ukraine’s performance. While seven of the fifteen countries gave Ukraine zero points from juries, only one of those juries (from Ireland) ranked Ukraine outside of the top five. The spread of results that Ukraine received from these juries is as wide as for any competing nation.

However 10 of the 15 nations gave Ukraine douze points in the televote, a proportion of 2/3rds that is roughly equal to the 28/39 nations that gave Ukraine their maximum in May.

Conclusion: In May, the Junior Eurovision voting countries were not the most supportive group to Ukraine on the scoreboard, but Ukraine scored many high scores from individual juries nevertheless. Televoting support for Ukraine was equally as strong as the entire collection of countries in May.

We cautiously predict from this that Ukraine will score big with some juries on Sunday at Junior Eurovision, and that will be enough to keep itself within touching distance.

But the way Junior Eurovision voting works the proportion of public votes going to Ukraine may get even higher.

Another Public Vote Landslide?

While the jury vote at Junior Eurovision may have enough Ukraine support to keep them in contention for the victory, we need to remember that the majority of Ukraine’s points in the 2022 Eurovision Song Contest came from the televote. It is the public vote in Junior Eurovision that is most different to how the Song Contest in May operates. At Junior Eurovision the public vote is an online vote, and each voter is allowed to vote for between 3 to 5 different songs once in the days before the show, and one further time immediately after all the performances have finished.

There’s an instinct here that Ukraine will do very well in such a voting system. If the voting public feels solidarity with Ukraine one is able to give a vote to Ukraine as well as giving votes to their home country and their favourite song. Rather than who would vote for Ukraine, perhaps in these crazy times we can ask who wouldn’t? It is very easy in this system to award Ukraine one of those three votes and as such there is a potential for the percentage of Ukraine voters to smash the figures that Kalush Orchestra received in May.

Conclusion: Ukraine is likely to receive increased public vote support due to the voting system requiring at least 3 votes per user.

However we must note that there is a mathematical cap to this public vote. The maximum public vote score one can receive in Junior Eurovision is 309 points. This number is ⅓ of the points that the online vote can give out, which is only possible if every voter chooses Ukraine. Such a score is unrealistic. A more realistic landslide figure to look out for would be ⅙ of the online vote, 155 points, which is to receive votes from at most half the voting public. This was roughly the same proportion that runaway winner ‘Superhero’ received in 2019.

Because the Junior Eurovision voting from the online vote is proportional it is hard for one song to storm the online vote to such a degree. There are two reasons why I believe Poland did storm the online vote in 2019. Firstly ‘Superhero’ was a smash hit pop song that was catchy, well performed (second with juries) and stood out from the competition. You know, the usual. However the second factor is that nearly half of the viewing public that year were living in Poland, ready and able to vote for their own hit single. The harsh fact of the matter is that the correlation between viewing public and online vote percentage is incredibly strong, and it doesn’t take a genius to work out why.

Now Ukraine has not had huge Junior Eurovision viewing figures (2020 figures suggest the viewing population in Ukraine was 1/20th of that in Poland) and the nation has finished 4th, 16th, 6th and 5th with the online vote (in contrast Poland has been 1st, 1st, 9th and 2nd) . In Junior Eurovision terms, Ukraine generally is seen as a mid-tier nation. However this voting system, and the normal Junior Eurovision viewing demographics, should massively benefit Ukraine this year. That is because I can think of no stronger ally than Poland to support Ukraine.

Both the Polish jury (yes, the disqualified one) and televote gave Ukraine 12 points last May and no other nation in Europe has taken in more Ukrainian refugees in recent months than Poland, over 1.4 million. The only nation I can anticipate may match the Polish viewing figures domination would be the United Kingdom, where the show on BBC One may attract a multi-million viewership. Only a handful of nations will get anywhere close. Let us remember that United Kingdom is also a nation that has been keen to demonstrate a strong relationship and support for Ukraine that I can anticipate will subtly nudge the voting at Junior Eurovision.

Conclusion: While many voters may give their extra votes to Ukraine, that effect will likely be stronger for viewers from Poland and the United Kingdom, who together could form the majority of Junior Eurovision viewers.

Should Ukraine utterly dominate this public vote is also dependent in part on the other songs in the competition. If there are a clear one or two favourites that blow the other tracks out the water then Ukraine will have a hard time of landsliding the public vote. That is because these songs are also likely to receive points when viewers need to vote for multiple entries.

However if this year’s contest is an even playing field those votes that don’t go to Ukraine could end up being distributed from Ireland to Kazakhstan and every nation in-between. That flat distribution would make it easier for a Ukrainian victory to emerge.

What type of contest do we have this year? Probably somewhere in-between the two. Ranking communities such as on Discord or the Eurovision Scoreboard app show entries from the United Kingdom, Armenia, Georgia and The Netherlands as highly ranked, as well as notable support for Poland, Ireland and Spain. Yet none of these entries are truly dominating the pre-contest rankings in a way that one might expect they need to in order to match a Ukraine solidarity vote.

Conclusion: Junior Eurovision 2022 appears to lack a universal favourite candidate that could match any Ukraine landslide.

But in the above rankings where does Ukraine lie? Oh yes, way down snug in the bottom half of the leaderboard. Over two thousand words and we didn’t even get to discuss the song.

“God I Have One Question”

The Ukrainian act in question is 14 year old Zlata Dziunka, an experienced performer who has previously taken part in festivals in the Czech Republic, Lithuania and Poland. She was the chosen artist from a five-song national selection to choose the Ukrainian representative, performing there the song ‘Nezlamna (Unbreakable)’.

The song is a sincere and emotionally performed mid-tempo ballad. Zlata asks in the song’s opening “how long will this fierce war continue?” The song resolves that, despite the fact “the enemy is among us”, ultimately because “our will is unbreakable” they will be victorious. This is clear in the repeated closing lines of the song, “we will be strong, we will be free, we will win” (Lyrics in the above section were taken from the official translation of the Ukrainian lyrics as provided by the European Broadcasting Union).

It is impossible for any listener understanding these words to disassociate their usage with the current invasion of Ukraine by the Russian Federation. Indeed Zlata has commented in interviews how the song is “a prayer to God about all the grief caused to my country by the war.”

‘Stefania’ was not like this. Now ‘Stefania’ was written and selected before the invasion began, yet it did become one of the most notable pieces of music during the first few months of the invasion. Not just because of Eurovision success but also its story, about men wishing to hear their mother’s song once more, became something incredibly poignant as war struck and families were separated. In contrast, while ‘Stefania’ allowed for incredible personal connection, ‘Nezlamna (Unbreakable)’ tackles the big issues head on and is a heavy listen. , If Junior Eurovision fans pre-polling is to be believed, it’s not hitting the emotional get-out-the-phone-and-vote appeal it needs to. I’m struck by a quote from YouTube channel Overthinking It this spring.

“Sometimes telling a small story is the best way to let people connect with something too huge to feel all at once.”

Conclusion: Ukraine’s song still needs to have an emotional connection to secure those votes, and if ‘Nezlamna (Unbreakable)’ can do that is the big ‘what if’ question of this year’s competition.

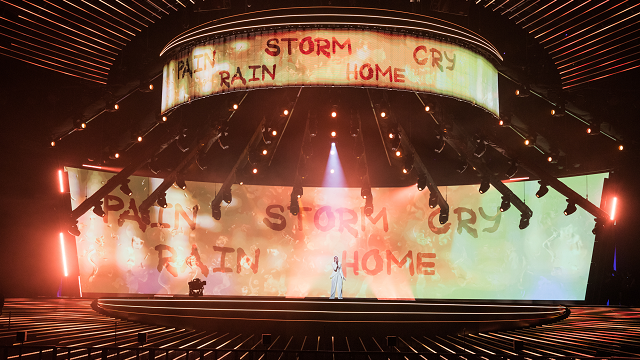

While the lyrics to the Ukrainian Junior Eurovision entry may be on the grand scale, the choice of storytelling in the music video elegantly touches on the smaller stories. That is particularly highlighted by the delicate use of other children in the story sharing the bunker with their families as they take shelter from the war above their head. The staging in Yerevan is similarly trying to share these emotions through interactions with the LED screen and choice words on the backdrop to remind us of the song’s heavy emotions.

Lyrics on the backdrop of Ukraine’s first rehearsal in Yerevan (Photo: Corinne Cumming, EBU)

Will this emotional connection translate to the scoreboard is what we will find out on Sunday, but the conversation in Yerevan certainly concludes that Ukraine are one of the favourites for victory. Either way I suspect Ukraine’s result will impact what we all think about the legacy of Kalush Orchestra’s victory. Another landslide Ukrainian success in Yerevan and the asterisk won’t ever be leaving Kalush’s win for many members of the community. However should Ukraine miss out on victory as fan polls suggest that would strongly suggest that there was something uniquely special about ‘Stefania’ outwith the country it represented that deserved that record televote score. That might be enough to put to bed any discussion about how deserved Ukraine’s victory in May was.

And in the middle of this is 14-year-old Zlata, living in a country that is fighting for its survival on a daily basis. If you got this far in reading this (I love you all) then you are the type of person who finds the voting and its associated drama fascinating. So it may be, but it is also prudent to remember that these stories of terror and fear, but also defiance and pride are brutally honest not just for Zlata (who did co-write the lyrics) but for millions in the Ukrainian nation.

Telling this story to Europe is more important than the position Ukraine gets on the scoreboard.