It was during the live broadcast of the Grand Final that we first heard of the voting irregularities in this year’s Eurovision Song Contest. Not on the broadcast itself, but a statement that was published just as the votes were set to be revealed, after all of the performances had aired.

“In the analysis of jury voting by the European Broadcasting Union’s (EBU) pan-European voting partner after the Second Dress Rehearsal of the Second Semi-Final of the 2022 Eurovision Song Contest, certain irregular voting patterns were identified in the results of six countries.

In order to comply with the Contest’s Voting Instructions, the EBU worked with its voting partner to calculate a substitute aggregated result for each country concerned for both the Second Semi Final and the Grand Final (calculated based on the results of other countries with similar voting records).”

Immediately after the Grand Final one was able to go through the official Eurovision website to find the rankings for both jury voting and televoting from each nation. However, the data from six broadcasters was not made public. This made it easy to establish which six countries had their votes annulled… namely Azerbaijan, Georgia, Montenegro, Poland, Romania, and San Marino.

In this article, we look at two things. Firstly what those irregular voting patterns were and the rationale for excluding them. Secondly, we investigate the way the replacement results for these nations were calculated.

The Rationale for Disqualification

On May 19th, a few days after the Eurovision Grand Final, the EBU revealed more information about the rationale behind the removal of these scores. With that the EBU also released their criteria to justify the removal of such scoring:

- Deviation from the norm (compared to other professional jurors elsewhere).

- Voting patterns (are there visible patterns clear in the data?).

- Irregularities (did the jury follow the Eurovision rulebook?).

- Re-occuring patterns (do other countries vote in a similar pattern?).

- Beneficiaries (does this voting irregularity provide a notable benefit to certain nations?).

The EBU also explained that for a vote to be considered irregular it would need to meet two of the above five criteria. The way these countries’ broadcasters voted in the Second Semi Final hit many of these criteria, as the EBU subsequently revealed.

“In the Second Semi-Final, it was observed that four of the six juries all placed five of the other countries in their Top Five (taking into account they could not vote for themselves); one jury voted for the same five countries in their Top 6; and the last of the six juries placed four of the others in the Top 4 and the fifth in their Top 7. Four of the six received at least one set of 12 points which is the maximum that can be awarded.”

While that is a huge list of differences, this statement alone doesn’t best demonstrate the dramatic scale this voting pattern holds. It wasn’t just that these juries voted for each other, it was that very few others did.

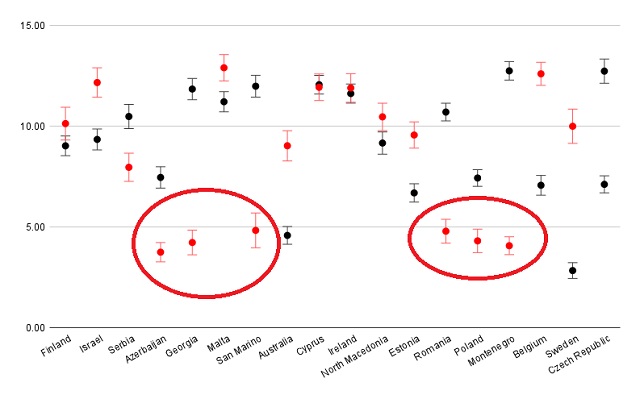

On the graph below the red dots show the average (mean) ranking of each nation by each juror from these six disqualified jurors from the second semi final, and the black dots are the average ranking from the non-disqualified jurors. The error bars show one standard deviation above and below the calculated mean.

The six data points circled are from the same six juries that were disqualified. Those six juries ranked each other significantly higher than what the other nations considered their performances should be.

What is most obvious when observing this graph is that those six countries that saw their juries disqualified all scored significantly higher than each other than from the other nations. What makes the pattern outstanding and clearly visible is how four of these six nations scored very poorly (in non-qualifying positions) in comparison to the votes from these six nations. It is therefore easy to argue that this group of jurors did deviate from the norm (a Pearson’s correlation analysis of these two data sets has a value of -0.19, a negative correlation meaning the average rankings disagree more than they agree), while producing a voting pattern that was not just visible but hugely benefitted each of the six nations concerned.

Assuming the aim here is to qualify for the Eurovision Grand Final, we can even argue that the lowest-ranking nations that ranked worst from these juries, Malta, Belgium, Israel, Cyprus, and Ireland, also were beneficial picks. These were nations considered to be marginal qualifiers in the build-up, so pushing these nations out to get low/zero scores would help benefit any of these six should a closely fought battle for the final qualification positions become a reality. Even this voting pattern appeared to best benefit the six nations concerned.

Given this data correlation and given the criteria at the EBU’s disposal to remove a jury vote, the decision to remove these juries is easy to argue for. However, it is the aftermath of what these mean that is so sensitive. The EBU statement is not about observed cheating within the jury rooms, or through fabled brown envelopes being passed between delegation, but instead purely based on mathematics. The argument is purely that the professional jury ranking is so different to the others that the decision is that it can not be a professional judgment.

Yet while the average for each of these songs was significantly lower with the other jury groups, some of the non-disqualified juries placed these songs well. 8 of the 70 other jurors had Azerbaijan in first place in the Second Semi Final, with San Marino, Montenegro, Romania and Georgia all being placed first by at least one other juror as well. While it is mathematically highly unlikely that the two populations (the six annulled juries vs. the other juries) would naturally have such different rankings, this does show that even some approved jurors did believe these songs could have been as highly ranked as the removed results did.

As one would expect, this has opened up a difficult can of worms for the EBU’s relationship with those six broadcasters. Romanian broadcaster TVR released a statement explaining that the extraordinary situation “surprised us unpleasantly” and felt dismayed that the broadcaster was given no advance warning on the decision. Polish broadcaster TVP claimed that the EBU’s reasoning was “groundless and ridiculous”, and San Marino’s SMRTV expressed their opinion that the EBU’s handling was “authoritarian” and that they had “disappointment” with the EBU’s handling of the situation.

The disqualification of the juries wasn’t the only thing these broadcasters were unhappy about. The other problem was what they were replaced with.

What Happens When A Jury Vote Is Disqualified?

The process that happens when a jury vote or a televote is unable to be used is one of the mysteries that still surround the voting system at the Eurovision Song Contest. The process is that any vote that can not be used is replaced by an aggregate ranking made up of a pre-determined set of juries, based on those that have “similar voting records”. These are not formally revealed, not even to affected broadcasters.

This practice of using similar voting records is used normally to divide up nations in the Eurovision Song Contest early each calendar year. The Semi Final Allocation Draw divides up broadcasters into one of the two Semi Finals, with the nations this year being seeded into six different pots based on their historical voting patterns. The process then ensures that half of the nations in each pot compete in Semi Final One, and half in Semi Final Two, so no one Semi Final is dominated by broadcasters with a track record of voting for each other. In practice, this results in a blend of north/south and east/west amongst both Semi Finals.

A similar division process has been used for the replacement of jury scores. In 2019 the jury from Belarus was disqualified because the jurors had publicly commented on which performances from the Semi Final were their favourites. After the Contest, it was calculated that an average of the 4 nations that were in Belarus’ pot were used to calculate the score Belarus eventually awarded.

The methodology in 2022 was also based on historical voting patterns. Both the disqualified nations Georgia and Azerbaijan were in the same pot as Ukraine, Armenia and Israel (and historically Russia, who were disqualified from Eurovision 2022). Unsurprisingly, the points awarded by Georgia and Azerbaijan in the Eurovision Grand Final this year were identical, and they are a perfect match to the average of the jurors from Ukraine, Armenia and Israel. (Both of these discoveries were first found in the Eurovision community by Portuguese Eurovision fan EuroBruno, who we interviewed on ESC Insight over the summer)

For those broadcasters who have seen their results replaced in the live broadcast, the outcome of this has been less than ideal. In their statements the Polish, Romanian and Sammarinese broadcasters revealed that their juries had planned to award 12 points to Ukraine, Moldova and Italy respectively.

These were highly charged picks given the world today for different reasons. Poland has taken in the highest number of Ukrainian refugees of all the competing nations since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine which began in February of this year. Moldova’s Eurovision entry was in the Romanian language and about the shared culture between the Moldova and Romania. Italy, which surrounds the Sammarinese microstate in all directions, entered with what was the biggest Italian-language hit in years during the spring of 2022.

We can talk about this and that about political voting in the Eurovision Song Contest, but for these public service broadcasters awarding ‘douze points’ to each of these three entries would be a moment of pride that goes beyond the five jurors in question.

While Poland did reward Ukraine with 12 points in their calculated score, San Marino’s calculated score only gave ‘Brividi‘ 3 points and Romania awarded Moldova zero points.

The concept that one can replicate a jury vote from other juries did not work as well as these broadcasters would have wished. It is much harder for the EBU’s methodology to work well when looking at juries rather than televotes. It is little surprise that the variance is smaller between songs that do well with televoting, where millions vote around the continent, rather than from juries made of five people.

Perhaps that variance is too high to make this calculation viable.

Pick A Country, Any Country

We know that the EBU uses a method where the competing nations are divided into pots based on their voting data. We can use data from this year’s Eurovision Song Contest to assess if this provides a statistically good replacement of the juries.

To assess this we take the jury rankings for the Grand Final for all the nations that had juries vote from the six pots used by the EBU for the Semi Final Allocation Draw (29 in total). What we then do is calculate a Pearson’s correlation coefficient for each jury ranking compared to others in the same pot as them.

For example, Albania in Pot 1 is together with Croatia, North Macedonia, Serbia and Slovenia (Montenegro was removed as their jury was disqualified). We calculated 10 different correlation coefficients for these rankings, so every pair has been calculated. Then we take the average of the 10 calculated coefficients, which gives us an understanding of how well the nations in pot 1 correlate to each other.

In theory, a number of +1.00 here would suggest perfect correlation, and that all of the juries voted identical to each other. Conversely a score of -1.00 would suggest perfect negative correlation, meaning the juries voted completely the opposite of each other. A number of 0.00 would indicate that there is no pattern between highly and lowly ranked songs in this data.

Here are the results for the six different pots that we investigated

| Pot Number | Nations in pot | Average Correlation coefficient |

| Pot 1 | Albania, Croatia, North Macedonia, Serbia, Slovenia | +0.35 |

| Pot 2 | Australia, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden | +0.39 |

| Pot 3 | Armenia, Israel, Ukraine | +0.21 |

| Pot 4 | Bulgaria, Cyprus, Greece, Malta, Portugal | +0.20 |

| Pot 5 | Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova | +0.55 |

| Pot 6 | Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Ireland, Netherlands, Switzerland | +0.55 |

| Average | +0.375 |

Statistically speaking all of these six pots show a positive correlation, meaning that the votes from the juries are more similar than they are dissimilar, which is most true for the nations in pots 5 and 6. While these numbers are not suggesting a perfect correlation, a perfect correlation is not desirable (it would almost certainly trigger the EBU to question the legitimacy of such results). As Hernstein and Murray quote in their 1994 book ‘The Bell Curve’ (available online here), generally in social sciences, the variance of people is so high that correlations are “seldom much higher than +0.5” due to the differences within humans. In this instance, the difference is of course the opinions that each juror has about the songs and the performances.

This figure of +0.375 is therefore plenty good enough to suggest that using other juries to replace removed juries is a good fit.

But a good fit compared to what? A value of 0.00 would indicate simply that the results are not correlated to each other – that the rankings were completely random and independent of each other. Replacing with juries is one thing, but are we replacing with the correct juries?

Let us investigate the results of each of the nations in the above table compared to average rankings from each of the different pots. Taking Albania as an example again, I undertook the same correlation analysis on the final ranking produced by Albania’s jury to an average ranking of all the other nations in pot 1, as well as to the average ranking of the nations in the five other pots. The results of that are below.

| Pot Number | Correlation Coefficient | Correlation Coefficient Ranking |

| Pot 1 | +0.57 | 5th |

| Pot 2 | +0.69 | 3rd |

| Pot 3 | +0.63 | 4th |

| Pot 4 | +0.53 | 6th |

| Pot 5 | +0.79 | 1st |

| Pot 6 | +0.71 | 2nd |

The Albanian jury here showed high correlation to other juries, peaking at a value of +0.79 (Albania’s jury did give points to 8 of the eventual jury top 10, so a high correlation is expected from this nation to others). However what is notable is that the highest correlation is not from the countries that are in the same pot as Albania, but in this case from the four nations calculated in pot 5. Indeed, the relative ranking of the pot 1 nations is only the 5th best correlating group of all of the rest to Albania’s jury.

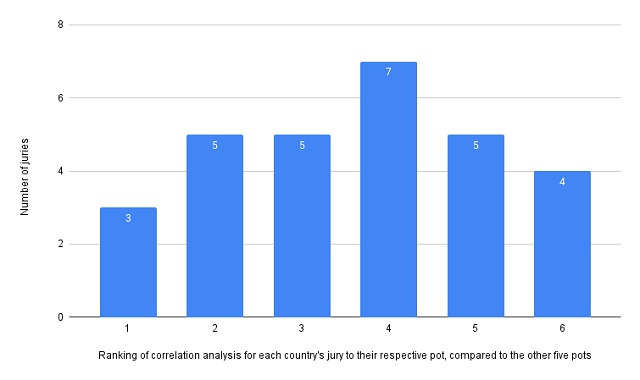

This pattern repeats for the other nations in this data analysis. Of the 29 juries that we investigate here only three of them are best correlated to the nations in their pre-determined pot – and on four of the occasions the pre-designated pot was found to be the worst fit for the jury scores. The following chart shows where each nation’s pot ranked compared to the other pots. A ranking of 1st means the countries in their pot match best, and 6th means their own pot is the worst fit of the six options.

This chart shows the relative rankings of each country’s jury compared to the other pots that the EBU uses. There is practically zero correlation that the pots the EBU uses are the right pots to take the sample from.

This chart clearly shows how there is apparently equal chance of correlating highest to the juries from the same pot as there is correlating lowest to it. We have earlier established that using the results from other countries is better than a random set of data. However this result suggests that which countries data we take is of zero significance and any group of random countries would get a result of equal quality. In predicting the rankings of Eurovision Song Contest juries the use of pots and historical voting data to predict the jury rankings is a fortuitous tool.

A Lose-Lose Situation

It is clear that replacing a jury is a lose-lose situation – both in having to do so and the actual result that it then calculates. The broadcasters are unhappy with the fact that the results from their nation do not represent what they want to share to Europe. This is especially true as the reveal of the televote is now conglomerated with all of the other scores from across Europe, so the “Hello from Warsaw” moment is only for the jury score.

Statistically the way the replacement is calculated is no better than any other combination of countries, and the results that are then presented don’t represent any accurate picture of what that jury would like to show to the world.

Let’s remind you that during the broadcast no mention of any fraudulent voting occurred, and the majority of fans would believe the votes from the Sammarinese spokesperson would have been the votes from the Sammarinese jury, not created from people outside its borders. It’s nigh on impossible but any replacement system that didn’t produce 12 points to Italy from San Marino or to Moldova from Romania is never going to be seen as an acceptable replacement.

Of course one hopes there is never a reason ever again to remove a jury from the Eurovision Song Contest voting. While we have explained the rationale that the EBU have made to do so this year, and conclude that it does fit the criteria the EBU have for taking such action, we must note that the affected broadcasters have strongly defended their jurors. And remember the only evidence we have been presented with was their off-kilter voting patterns from the second Semi Final.

However I note that the Romanian broadcaster also decided in the aftermath to reveal the jury scores that they were set out to publish. The same five jurors who voted on the Grand Final also voted on the songs in the Second Semi Final. We can compare the relative rankings of the nine songs that Romania could vote for that took part in both shows, and see if there are changes. The average rankings from jurors from the Semi Final to the Grand Final have a near-perfect correlation of +0.91. This means that the way the jurors ranked these nine songs in the Semi Final practically is identical to how they were ranked in the Grand Final. If we are suspecting that the Semi Final vote was a corrupt taste then it would be a surprise to see the same voting trends for the Grand Final once the dirty deeds were done.

Of course these votes may be equally as fraudulent as the EBU believe them to be. Yet somehow it does offer the tiniest slither of evidence that the Romanian jury were genuine in their taste that ‘Hold Me Closer’ was the second worst song of the Semi Final, when they also ranked 20th in the Grand Final as well. I’ll leave the speculation of genuine voting intention or not up to you.

While the 2022 situation may not please everybody and outcome may be an unsatisfactory one, the scoreboard on last season’s Contest is now settled. But the farcical situation that these disqualifications created is one that should never be replicated ever again.

Why are using r for variables that are ordinal: ANOVA would make more sense–particularly since there’s no Gaussian distribution of either Eurovision scores or jury members’ ordinal rankings. We also don’t know anything about the difference between two consecutively ranked entries: the higher ranked one could be considered much much better than the next ranked one.

Who would have believed that Pearson’s r would ever feature on a website about pop music? Great analysis, Ben. Can’t say I understood much of it!!!

The important thing is that the EBU put a marker down and that will hopefully make juries think more carefully about vote swapping and the like in future?

Does the EBU’s system counteract the practice of negative voting where certain juries always rank a particular country bottom and never award them any points?