37 countries will take part in Eurovision 2023. The withdrawals of Bulgaria, North Macedonia and Montenegro, without anybody else returning or debuting, means that the show will have its lowest number of participating countries in nine years.

With Ukraine being given the right to go into the Grand Final automatically as previous winners alongside the Big 5, we will have two Semi Finals and over four hours of programming will be used to eliminate just 11 songs. One of this year’s Semi Finals will have 15 songs, with ten qualifying to Saturday night.

Ukraine is doing more than going straight into the Grand Final. Together with the BBC and the City of Liverpool, the show is being hosted in the United Kingdom on the behalf of Ukraine. This double hosting has such cultural importance that more time must be given to make this unique collaboration a success. This is the year when 18 qualifiers from the Semi Finals will be more than sufficient for a competitive Contest of 24 songs, whilst offering more time to represent Ukraine in the Liverpool Arena.

Let us explain why this year more than ever would be the right year to cut this number, and let’s start that journey in Copenhagen and the Eurovision Song Contest 2014.

From Eurovision Island In Copenhagen

There is an obvious similarity between the world of 2014 to the world of today. Back then public purse strings were being tightened as the European Debt Crisis took hold and broadcasters saw budgets slashed. Cuts were so deep that even stalwarts of the modern era like Cyprus, Croatia and Serbia chose to take a step back from competing in Copenhagen.

Now let me make it clear that the Eurovision from Copenhagen, as a spectacle, was stunning. From a competitive standpoint though it was a lacklustre edition. Let me pick out the Second Semi Final, that of 15 songs, for me to critique. In particular let’s start with the countries in the bottom 4 with the juries – which ended up with jury points (note that this year jury and televote scores were ultimately combined, but data afterwards means it is possible to calculate) scoring 31, 32, 32 and 33 points respectively. Effectively this narrow range is random noise, the threshold to score points is so low, that even the ‘worst’ of these entries scrapes into the top 10 often enough to pick up the odd score.

The 2014 Contest provided at the time the best-detailed statistics about contest voting in its aftermath, being the first to release the full juror and televote rankings. I analysed these a lot at the time, and you can go back and read those old articles here. One thing I investigated were the songs where jurors were in agreement, and where they were not. This concluded that some songs were middle-of-the-road, and some were pure marmite. In these smaller Semi Finals we can see that both of these extremes have a point of symmetry roughly around the same ranking.

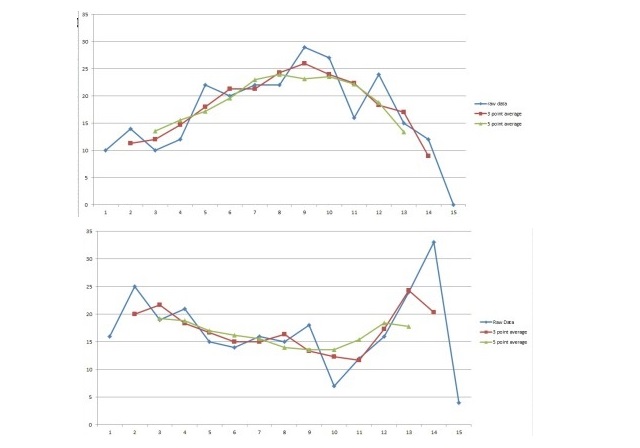

Graphs showing the ranking of songs in the Second Semi Final of the Eurovision Song Contest 2014.

These graphs show the raw data, as well as 3-point and 5-point moving averages, for song rankings by jurors from the second Semi Final of Eurovision 2014. The graph above shows the rankings for songs with the three smallest standard deviations (i.e. jurors had most agreement on) in ranking between the jurors, and the graph below shows the same data but for the three songs the jurors most disagreed upon.

Following the data above it suggests that judging the songs changes once a juror got to around 9th place in these smaller Semi Finals. For those songs that have much jury agreement in their ranking, those values have a maximum around 9th place. Alternatively those songs were jurors disagree have a minimum around 9th place.

My interpretation is that the top eight or so songs were songs that were ‘liked’ in varying amounts. The rankings below that show how much a song was relatively disliked compared to the others. Songs such as ‘Slavic Girls’ and ‘Moustache’ were big examples that year where a small minority of jurors ranked them highly but a vast majority of jurors ranked extremely low. These songs were more likely to be ranked in the top five or bottom five by jurors than they were to be placed in the middle.

The song that took the 10th and final qualifying spot in that 15-song show was the complete antithesis to those provocative attempts I mention above. Indeed I would argue that one song is the least disliked Grand Final song of the last ten years.

You Don’t Know Is It Love Is It Hate?

I’m referring to ‘Round and Round’, the Slovenian entry from 2014 performed by Tinkara Kovač. Tinkara qualified by finishing eighth with juries in the Semi Final and ninth with televoters, but that combined together was only enough for tenth place in that show to take the final spot in the Grand Final.

Everything about ‘Round and Round’ screams Eurovision Song Contest. It features a language change, an instrumental solo, a four-chord chorus loop and lyrics that dance around the topic of love without necessarily committing to any strong statement (after all, the characters are going “round and round” each other). This Slovenian entry was an absolutely perfectly well-functioning pop song that nobody could possibly find offensive in any way.

The problem is that, while there was a market for a well-performed and formula-following pop song in a small Eurovision Semi Final, Slovenia saw itself completely outclassed by other options in the Grand Final. Ultimately Slovenia finished second last with 9 points from just two countries.

This song was not ranked ‘worst’ though if you look at the full rankings – indeed with juries Tinkara received a perfectly reasonable average ranking of 15.03 out of the 26 competing entries. The problem was that ‘Round and Round’ sat exactly on that threshold in-between likeable and unlikeable art. That middling jury score was backed up by the smallest standard deviation of any of the competing entries in that Eurovision Grand Final – few Eurovision jurors disagreed with a middling ranking for this entry. This was, mathematically speaking, the most average song of the 2014 Eurovision Song Contest.

And, to repeat, the Slovenian Eurovision entry of 2014 was a perfectly good three minutes of pop music, but ultimately it was the entry more than any other that passed people by, that failed to invoke strong opinions, and was anonymous when against a stronger field. Eurovision finalists need to cut through the intense noise to succeed. These types of non-committal songs are the ones most likely to squeak through in small Semi Finals, and they are unlikely to grab the attention of anybody on a Saturday night.

Allowing two-thirds of all competing entries a pass to the Grand Final again is a mistake that I don’t want to see repeated.

Lessons From Around Europe

It was notable that the 2022 Eurovision Song Contest season included an increased number of National Finals from participating broadcasters, with Spain, Serbia and Romania amongst others that moved away from internal selections the previous year.

I measure 13 of last season’s National Finals as having a recognised multi-show National Final system that includes some form of Semi Final elimination round (not including events like Italy’s Sanremo in this list, but I do include the songs going from Melodifestivalen’s four heats into their Final). Here broadcasters across the continent can choose their own rules for their shows. How many songs do they want in their final, and how many should qualify from each Semi Final?

The statistic I am measuring is the number of songs from each Semi Final that ultimately end up making the Final of their respective show. For example in Eesti Laul, Estonia’s selection process, the Semi Final shows there contain ten songs of which five get eliminated. This 50/50 ratio of qualifying/not-qualifying is the most common, featuring in 6 of the 13 shows we analysed.

Most other broadcasters fall very close to this value (some with odd numbers of competitors are as close as they mathematically can be), and only two broadcasters would allow more than 60% of the competing entries a chance to qualify to their respective final (Latvia had 11/17 qualifiers, Malta featured 17/22).

The upcoming Eurovision Song Contest outcome where 10 songs qualify from 15 competitors would sit alongside Latvia and Malta as outliers in this list. The collective heads of the continent’s public broadcasters seem to agree that eliminating roughly half the songs is about right when they get their hands on producing their own Eurovision selection. This amount gives the right number of ‘quality’ acts progressing to their Final while still allowing the variety of acts needed to attract viewing figures and make a spectacle of musical entertainment.

Now, these National Finals have the luxury of course of allowing as many entries to take part as they wish, whereas the Eurovision Song Contest requires broadcasters to pay substantial entry fees which affects participation numbers. And while the maximum number of countries in the Song Contest each year is set by the number of broadcasters willing to pay (technically there is a limit in the rules of 44 countries that has never been hit), a minimum number has not been codified.

This is true as well for the Grand Final which can have a maximum of 26 participating countries, but no minimum. And if there ever was a year when we might need to chop off some time for the Saturday night show, this year might be the year to do it.

From Liverpool To Odesa

The 2022 Eurovision Song Contest was won by Ukraine. The Ukrainian broadcaster wanted to host the Eurovision Song Contest in their home country, yet due to “safety and security issues” the decision was taken to ask the broadcaster of the United Kingdom, who finished in second place, to find a suitable venue.

The host city they ultimately chose after a long bidding process was Liverpool. Liverpool is no neutral host city. Liverpool is a culturally vibrant global city, a UNESCO city of music and one proud of itself and telling its story to the world. Liverpool as a city will have plenty to showcase that starts with The Beatles but certainly will not end there.

I have also been impressed by the political astuteness of those representing the bid from the City of Liverpool. Each representative is fully aware that they are hosting the Eurovision Song Contest under special circumstances and has reminded the media at every opportunity that this show will be hosted on behalf of Ukraine. Councillor Roy Gladden, Lord Mayor of Liverpool, even described the victory as “bitter-sweet” in an open letter to his counterpart in Liverpool’s twin city of Odesa, making it clear that “we know this is your event.”

So for every bit of scouse twang that crops up in the show a slice of Ukrainian vocab should appear side-by-side. For every interval act from the UK another one from Ukraine should perform for their nation. Time should be given to allow the Contest to remember why it is not in Eastern Europe this year and to make a celebration of Ukrainian culture that will show all the values of universality and inclusivity that is Eurovision.

But that takes time. It is normal to have Eurovision host countries and cities put on a great cultural show and so much will be the same next year. But next year needs double as much time than any hosting previously. Less and we are doing a disservice to both the people of Liverpool, the people of Ukraine, and in general to the importance of hosting Eurovision to the continent in these uncertain times.

You Got To Give Me More Time

The problem is that this resource of time. The Grand Final of the 2014 Eurovision Song Contest was meant to last 3 hours and 30 minutes. It ended up overrunning an extra five minutes. Since then the running time of the Eurovision Song Contest has slowly crept up, with the 2022 edition scheduled to run for 3 hours and 50 minutes (which eventually crept up to over four hours). Now almost all the viewers are finding out who has won the Song Contest well after midnight. The number of songs may not have increased but everything else surrounding the shows has got bloated.

This year that bloat has more importance than ever and needs to be given the full focus it deserves so both host countries get to celebrate their hosting through the show. But we need to find ways of doing that so that we don’t accept a show running longer than four hours – for every minute the show continues to go we risk less and less viewers staying up to watch the exciting finale.

Removing two countries from the Grand Final is a drastic and risky step. For a start I concede this on paper will result in less viewers from at least two other countries on the Saturday night to which many broadcasters may react conservatively in fear of missing out. Yet that negates the risk that the Eurovision shows themselves will be worse with a 26-song show.

A 26-song finale would mean either less time for our two host countries to properly host, or a show that drags on late and loses viewers that way. It means as well that our Semi Finals would be far too uncompetitive – making the broadcasts of them less exciting and nerve-jangling for those already well aware they are expecting to score well on the Saturday night.

We also ultimately have two extra songs we don’t need in the Eurovision Song Contest final. By the nature of how jurors rank songs on a positive/negative scaling we are more likely to see songs that are Eurovision wallpaper sneaking into these final qualifying positions, rather than those that at least challenge the viewer to pay attention to them. You need more of the latter on the Saturday night, but small Semi Finals favour the former.

Change It Next Year And Keep It

And while the co-hosting between Liverpool and Ukraine may be the excuse we need to run a 24 song Eurovision Grand Final this coming year, why don’t we keep it at that number going forward? Long term this change could help the Contest conclude within 3 hours and 30 minutes once more. This time limit does put the show well beyond the bedtime of children living in CET but maybe just maybe exciting enough that those old enough to understand the mathematics as the waves of points flood in might be able to make it through to the bitter end.

The Eurovision Song Contest Final should be the ultimate in musical variety entertainment and should be something that can reach all. Running a show for over two hours that ultimately succeeds in cutting fifteen minutes of said entertainment weakens the Saturday night product. The time will never be better than now for the EBU to trim eight minutes of competitive content from the Grand Final.

Once again excellent analysis Ben. It makes sense. You always surprise me welldone