In the last decade finding hosts for Junior Eurovision has sometimes been tricky. For example after Italy won the 2014 edition they waived their option of being the host country, and instead the show went to Sofia. With many broadcasters struggling to prioritise hosting such an event after winning, the EBU tried a model where countries could bid to host before Junior Eurovision took place. Back in 2017 former EBU Head of Live Events Jon Ola Sand argued this model “protects the future of the Junior Eurovision Song Contest”, as it ensures there is always a willing host in advance.

That was no issue this year. On Sunday 24th November Valentina won both the jury vote and public vote to win Junior Eurovision 2020. By December 9th the French broadcaster had confirmed that they were ready to host. We eventually heard later in 2021 that Paris would be the host city, but we also know now that both Nice and Cannes on the Mediterranean coast were in the running to host – showing there was plenty of interest in bringing the event home.

And it is reasonable to think that, in our previous lives twelve months ago, representatives of Paris, Nice and Cannes would have been hopeful that the world was to be a better place than it was then. While the COVID-19 pandemic hit Europe hard in the winter of 2020-21, so too did the fightback, with a vaccination drive that means today more than 70% of adults in the EU are vaccinated.

And things are better today in the world of entertainment than they were last year. The 2020 edition of Junior Eurovision was held remotely, and delegations had to build replica stages in their host country or travel before the show to Warsaw to record their performance. This year the plans are that the show will get to go ahead in Paris with all the acts on stage. However plenty of adaptations have had to be made to keep this show alive.

The Plans Against Covid

Much of the inspiration for how to run Junior Eurovision this year will have been carried over from the 2021 Eurovision Song Contest. All acts made it there to Rotterdam and there was even a live audience in place (albeit an audience that was limited in capacity and a formal Dutch government test event).

For the show in Paris the same limit of 3,500 people is being used. This brings the capacity inside the spectacular La Seine Musicale hosting venue down by almost half. Those wishing to attend the show will need to arrive at the show at least 90 minutes before it begins, wear a face mask for the show’s duration and have access to the French government’s health pass (Passe Sanitaire). This pass, which all over 12 years and 2 months must show, documents if the person in question has either a complete vaccination program, a negative test result for COVID-19 in the last 72 hours or a documented recovery from the disease from at least six months prior.

This is to go above and beyond some of the other restrictions that participants, delegations and their families may have had in their journey to Paris. Those who are over 12 years of age and travelling to France need to report a negative COVID-19 test. The only exception for this is those who reside within the EU who must instead be fully vaccinated.

Once on the ground all involved with Junior Eurovision must follow the 24 page Health and Safety Protocol for this year’s show. Inside it is documented that there is a protection bubble around the nineteen delegations. This entails:

- The only travel is to the venue and to the hotel. Other sites are only accessible for certain filming purposes.

- Limiting interactions and only allowed those with accreditation to stay at the hotel

- No social programme for the delegations and no EuroClub

- Centralisation of meals at both the venue and the hotel

Further to this, there is a plan that all delegations, volunteers and staff will have access to scheduled testing for COVID-19.

For journalists on site one of the differences planned from a normal Junior Eurovision is that there is plenty of space. The press room has not been diminished in size but has been reduced in capacity to 175. Despite this, no online press centre solution like from Rotterdam this May is in action at Junior Eurovision. Journalists were also asked to keep a two metre distance at all times but especially during interviews, with a requirement not to use microphones that require close contact to the artist/delegation.

And Then Comes The Variant

The adaptations above were planned and expected by the European Broadcasting Union, with the Health and Safety Protocol and requirements to enter La Seine Musicale clear many weeks ago.

Since then, the latest development in the COVID-19 pandemic comes from the spread of the Omicron variant. On the 26th November the World Health Organisation treated this new variant of the disease as a “variant of concern.” Early studies show that this variant appears to transmit easier than previous versions and the extra mutations mean the protection from both vaccines and previous COVID-19 disease may be weaker.

This has put an extra spanner into the work to keep Junior Eurovision going and to keep the Health and Safety Protocol as strong enough to protect the artists in the show. Host broadcaster France Télévisions has strengthened this by making the Saturday night performance, the Jury Final, void of an audience and cancelling all previously sold tickets. The Opening Ceremony that was scheduled for Monday was reduced in scale, with no delegations invited to the event and therefore no red carpet for the artists.

For a journalistic perspective we spoke to Nisay Samreth, a French journalist writing for eurovision-fr.net. Nisay is a veteran of many Eurovision and Junior Eurovision contents and highlighted how these extra restrictions have made his work reporting on the contest harder. For a start, journalists are not allowed to enter the arena during not just the first but also the second rehearsals. This means for photographs of the stage Nisay and his team need to rely on the output by the host broadcaster and the EBU.

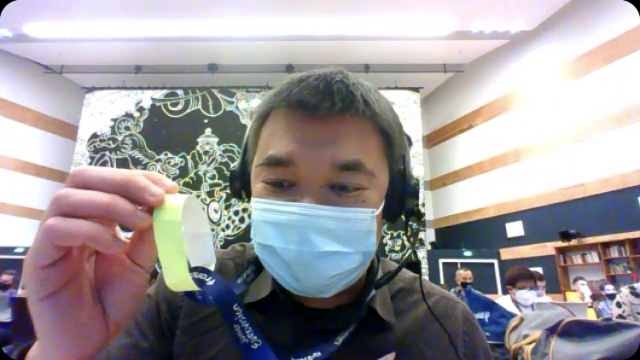

Thankfully getting access to the press centre is not such a challenge, the Passe Sanitaire is checked and, if approved, a yellow band is attached to your accreditation – meaning other people inside the arena know it has been checked that day.

Nisay Samrath demonstrating to me his yellow band on his Junior Eurovision accreditation

“The press centre is much quieter than in previous years,” Nisay tells me. “On the first day there was one member of the Dutch delegation who came by our desks, otherwise there was no one passing by”.

The requirement to be safe means that there is less interaction between artists, delegations and press, except for these formal interview moments that are regulated. It means that in the build up to the show establishing the big stories in the build-up and getting that buzz and attention can be more challenging.

But challenging is ok if it keeps the show going. With Norway announcing that no audience will be present at their Eurovision national final heats and Omicron rates in Europe increasing we know how vital it is to do all the steps necessary to allow Sunday’s show to shine.

Adult Decisions for a Junior Contest

Keeping a show like this on the ground in such difficult times is a challenge. One wants it to be all fun and games and joy but sadly there are adults needing to make very adult decisions about what can and can’t happen to ensure as many as possible – ideally all – can make it to Sunday’s live show and deliver the biggest performance of their lives.

There will be much relief from the European Broadcasting Union that all of the acts managed to perform at least one runthrough on the stage in Paris already. This means that there is a tape that can be used if need be due to later illness – as what had to be used for Iceland in May. This is especially important at an event like Junior Eurovision where the budgets are far more limited than at the main Eurovision Song Contest. We note here how countries were not asked to provide a back-up tape of their performance for that reason.

There will be a show on Sunday. It is a shame the world is like the way it is, but I am grateful that the show will be there, and that it can be the celebration these kids deserve.