The big question of the Eurovision 2019 season has been one that I think is both absolutely vital and completely obvious What is the deal with Hatari?

We Are Saying What Everyone Is Screaming

Art reflects the times. And these are wild and upsetting times, where it’s hard to see how we’ll make it through the next few decades without global thermonuclear war, catastrophic climate change, or a deadly outbreak of authoritarian fascism.

So what art do you make to express the fact that complacency is death, silence is complicity, and we’re all chained to a system that degrades and impoverishes us in order to make a small number of people meaninglessly rich?

What art do you make if you were born in the late 90s, and you’ve basically been raised by irony, meme culture and rolling news into a world that is on fire? What lyrics do you write when your biggest influences are Peaches and Noam Chomsky? What does the very last band in the world sound like?

When the world is flooded with images of destruction and chaos, this is the art we make when we fear are about to destroy ourselves.

Artifice And Facade

If you’re reading this because you just saw Hatari perform at the first Semi Final at Eurovision, and you’re confused and troubled by what you saw, let’s settle the basics first:

- No, they aren’t Satanists.

- No, they aren’t fascists.

- No, those two aren’t a couple.

- No, they don’t really want hatred to prevail.

What you just saw was some performance art, a slice of theatre, a 3 minute musical about how the world could end if we succumb to hatred. It was supposed to be alarming. If you were emotionally perturbed by it, it worked.

Hatari are a multimedia art group, centered on the apocalyptic techno music made by Matthías (the terrifying shouting dictator), Klemens (the short blonde, mulletty singer), and Einar (the masked, hammer-wielding figure of doom at the back) but encompassing visual arts, graphic design, dance, fashion, public relations pranks, fictitious beverages and a great deal of theatre. To name but a few things.

The group have created an alternate reality — a mythos if you like — around themselves. Their world-building is detailed, largely internally consistent, and they are using it for extensive storytelling. That’s how you know it is theatre. What has constantly amused me throughout Hatari’s Eurovision campaign is the lack of willingness to accept that what is being sung in a pop context is not necessarily the opinion of the singer. With Hatari, we’ve got to start to distinguish between the character and the artist. Everyone is acting. Everyone is wearing a mask — not just Einar.

We have seen these tropes before. They are not entirely new. We saw them in acts such as the comedy trio Doug Anthony All Stars from the early 90s and the underground anonymous techno group TISM – both hailing from Australia. We can also see traces of Hatari in group efforts such as Monty Python and The League of Gentlemen: both groups of wide-ranging talents, character and styles of performance all contributing to a greater piece of art.

Being a theatre performance, there’s all sorts of elements involved in making a Hatari show, including the production design, the costuming, the music, and the choreography. For the world building to work, every one of these elements has to be extreme, but also harmonious with the others. It seems like it’s quite an extra way of going about being a cult punk band, but when acts participating in the Song Contest think through the whole package on this level, that usually bodes quite well.

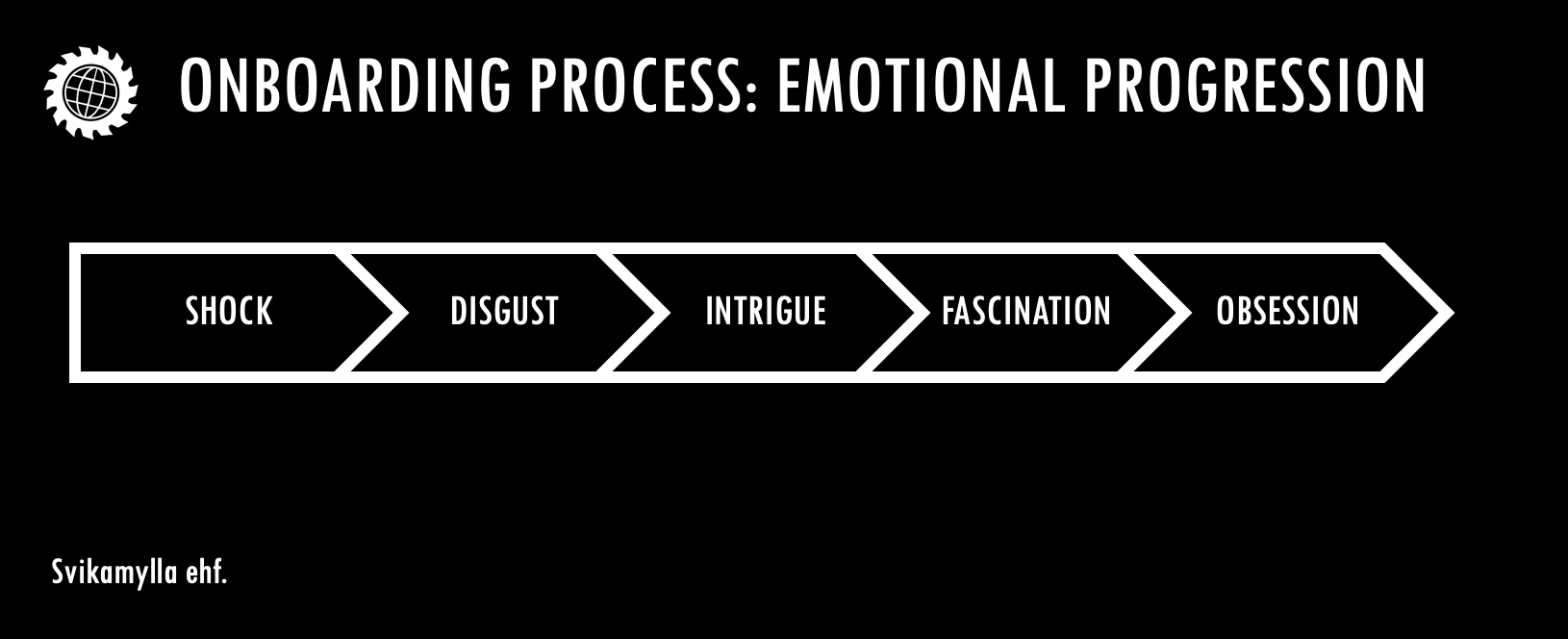

There’s a bit of an onboarding experience for new listeners to Hatari. You’re probably going through an emotional trajectory as described in this page scanned from a copy of the Svikamylla Employee handbook that I found in a bin on Laugavegur.

Onboarding to art (Laugavegur)

If you’re not used to a growled vocal or an extremely tough beat or the aesthetics of BDSM or industrial metal, then we need to go through a few things to get you oriented and relaxed before you can enjoy the world of Hatari. Like all good cinematic universes, we start off with the origin story.

Rule One: Hatari Lies

Hatari constantly lie about their origin story. I have heard half a dozen versions, but my favourite one was ‘Matthias and Klemens were taking a walk around Reykjavik in 2015 at sunset and we were thinking about the rise of populism and we were overcome with emotion.’ It doesn’t actually explain how or why this turned into a band, but it is sufficiently motivating. At least until you think about it.

The first recorded transmission from Planet Hatari was actually back in 2015, but the core trio in have known each other a long time – Matthias and Klemens are first cousins and grew up together in Reykjavik. At some point in the noughties, Klemens and Einar’s civil & diplomatic service-connected families both relocated to Brussels, where they studied at the International School. As far back as 2011 (they were 17 and 19 at the time) they were making music together in a project called ‘Far From Sea’ – no material has survived from this project. With their international baccalaureates complete, eventually Klemens & Einar both went back to Iceland and continued their musical collaboration with Kjurr, a moderately successful indie trio. Musically, it’s okay but not earth-shaking. It’s what everyone’s first bands sounded like in 2013.

With drummer Sólrún Mjöll Kjartansdóttir completing the line-up, Kjurr went through many of the rites of passage for members of the Icelandic music scene, including playing Iceland Airwaves and taking part in Iceland Music Experiment.

At some point in 2014, Kjurr stopped being a going concern. Klemens and Einar moved on to form Hatari with Matthias. While they’d been away in Brussels, Matthias had been studying Education and Drama and had started reporting for RÚV and Morgunblaðið. Nothing much happens in the Hatari-verse until the end of 2015, when they play a couple of small gigs and Odyr appears on a doom-laden compilation album Hid Myrka Man.

It’s not until Iceland Airwaves 2016 when things start to catch fire. This video captures what is supposedly their 6th ever gig, where the band are giving it full intensity in the lounge of the KEX Hostel, even as confused punters enter the venue from behind Einar’s drum setup. The early Hatari look played much more into a pseudo-fascist uniform aesthetic and there’s only really Einar’s mask that continues on from here.

Haukur Valdimarsson of up-and-coming Icelandic band Blödmor says:

“I remember when I saw HATARI for the first time. It was at a festival back in 2017. At first they looked very strange to me. Loud and heavy techno with growls was not exactly the thing I was expecting. But after seeing them multiple times I began to love the whole idea about the band and their awesome sound. When they released their EP ‘Neysluvara’ I completely fell in love.”

‘Neysluvara‘, or ‘Consumer Products’ is an EP of 5 songs, and was released on the band’s own Svikamylla (‘web of lies’) label. At this point, they’d started to appear on cultural segments on RÚV. Check them out in a shopping mall being deliberately weird and unhelpful, but setting out the key tenets of the Hatari plan: to dismantle capitalism from inside if possible, to expose the relentless scam of everyday life, and to draw aside the veil of irony and ambiguity in art.

So far so pretentious, you might think. But why can’t political music be danceable? Why can’t we use humour to send a serious message? Why can’t you do satire in an apparently shoplifted adidas tracksuit?

Sex, Contrast, And Balance

Talking to old school pre-Eurovision Hatari fans, and looking at archive footage, it seems like Hatari only really became Hatari when Klemens started getting sexy. Punters at their gig at Iceland Airwaves 2017 recall instant, magnetic fascination with him. That’s not to say that Matthias’s posturing and Einar’s mysterious presence don’t feature in people’s sensory memories, but there is a sense that when Klemens started really feeling himself and leaning into that subby and unconventionally masculine vibe, some sort of a balance was formed.

Hatari are made of contrasts. Matthías and Klemens are a study in duality – one dances, one remains stiff, one is dominant, one submits, one is harsh-voiced and one floats high and smooth. In Tel Aviv, they’re complying with the Eurovision process but bristling and pushing against it. They’re adjacent to pop but they’re also very, very much not. They’re spiky on the outside and soft on the inside. With the addition of Astros, Solbjorts and Andrean as dancers and backing singers, they’ve got someone for everyone to look at with hearteyes. They are the living embodiment of ‘get you a band that can do both’.

The Poem Is A Dead Art Form

So you just got into Hatari – let’s take a look at the components of their sound so you can expand your playlist beyond the seven officially released Hatari songs. Part of the joke of Hatari is that they’re hard to categorise sonically (to the extent that Reykjavik Grapevine never describes them the same way twice) but there are some elements that we can definitely pin down.

The synths and beats used in Hatari’s records lie somewhere between industrial music (sounding like clanging metal, machines grinding and sparks flying) and electroclash (sexy, decadent but lo-fi dance music from the early noughties). It seems like Einar is responsible for the production of these beats, and you can hear a cleaned up version of his electronica on the most recent album by his other band Vök. Without the vocals, the Hatari sound isn’t actually too far from more mainstream Nordic staples like Robyn and The Knife.

Klemens gives a post-rock vocal – a high falsetto drenched in reverb and delay to allow him to create harmonies and suspensions with his own vocal line. You’d definitely hear something like this in Sigur Ros, but this has got a bit more oomph to it. Matthías’s vocals are a barked metal growl. I’ve heard things just like it from extremely heavy bands like Rammstein, Napalm Death, Electric Wizard and a hundred Nordic nihilist metal bands of varying microgenres.

In terms of melodic hooks and the key change they brought in especially for ‘Hatrid mun sigra‘, the band claim to be following on in the tradition of ABBA. Maybe that’s not too far off as each of their songs has hooks throughout, even if they’re growled or shouted, but their semitone up keychange for Eurovision is certainly not lifted from ‘Waterloo’ which definitely starts and ends in the same key. When challenged, Klemens says ‘It’s a very subtle key-change’ and smiles winningly. Klemens distorts the truth, of course. The key-change is not subtle: it comes with a massive pyroblast and a dramatic drop to his knees, and the band has certainly used that semi-tone lift on the last chorus as a signifier that this song is for Eurovision. Adding in a keychange is quite a good way for a genre act to say ‘we know of your customs’ to a Eurovision audience. AWS went for it to great effect in 2018.

As far as Hatari’s overall musical attitude, you can also detect traces of Peaches (transgressive genderfucking electro) Depeche Mode (80s synth favourites occasionally playing with BDSM imagery) and Laibach (sarcastic, dead-eyed, highly political industrial music)

But what draws me to them is how closely they appear to be sticking to a plan for pop success laid out in the 1980s by The KLF – an art/novelty pop/rave/sinister happenings group formed by Bill Drummond and Jimmy Cauty. Most of what that band did was designed to attract attention, annoy people and get people asking the question ‘What is the deal with the KLF?’. The KLF story culminates with Drummond and Cauty burning £1 million, deleting all their records and appearing at the Brits in an extremely noisy and terrifying collaboration with Extreme Noise Terror.

I’ve often wondered how the KLF would have tackled Eurovision. I guess now I know.

Euroblindness And Complicity

So how do we get from a deliberately difficult cult band to Eurovision provocateurs? Going back to Haukur Valdimarsson:

“Back in December HATARI announced that they were going to quit so I was quick to get a ticket to their final show. A long time had passed since the last time I saw them. It is safe to say that they fulfilled my expectations. Their whole show had improved a lot since the last time I saw them. I was a bit skeptical about the whole idea of them calling it quits, so I was not very surprised when I saw that they were competing at the Icelandic Eurovision qualifiers.”

For a while, it looked like the creative community were dead set against Iceland sending a representative to compete in a contest hosted by Israel. With a small and interconnected music scene, a significant boycott of Songvakeppnin could have reduced an already limited pool of artists for the Icelandic broadcaster to pull from. It seems like Hatari’s participation in Songvakeppnin was already a done deal during their much-publicised farewell gig. The artists competing against them weren’t able to commandeer as much publicity as Hatari during the run up to Songvakeppnin. The Hatari stunts included announcing they’d signed up a conservative Christian figure who’d been loudly critical of them as a spokesperson, baking cakes in what can only be described as a deliberately normal manner, dancing with the enchanted children of Reykjavik, and passive-aggressively turning up to the Laugardalshöll Arena with a trailer twice the size of their nearest rival’s.

Hatari are trying to solve the problem of participation and protest within a contest that strongly believes that it is an apolitical event. The stunt of disbanding Hatari for failing to dismantle capitalism by a reasonable deadline marked a turning point. If you’re going to sell out, sell out for an idea, don’t sell out for money. Part of the Hatari plan leans into their increasingly extreme aesthetic: to use the juxtaposition of shocking counter-cultural imagery against banal pop to alarm and discomfort. They are using their credibility and constructed personas to test the limits of the rules and reveal the absurdity of insisting on the apolitical nature of an event laced with geopolitics, soft politics and historical score-settling disguised as innocent songs about family history.

If you are an artist of conscience participating in a contest held in a country that has practices you find abhorrent, you know you can’t sit and say nothing, but do you know what you can say? The rules are pretty clear: you cannot politicise or instrumentalise the contest. But we’ve had songs in favour of equal marriage, songs raising awareness of genocide, and from Israel themselves, songs about ending the conflict between Israel and Palestine. What we need to know is where do we draw the line? What constitutes politicisation? And does that line have more to do with what would embarrass the hosts or the EBU than a specifically quantifiable rule.

Artists like Hatari have realised that the line in the rules about politicising and instrumentalising the contest is porous. Provided you’re compliant and entertaining in other ways, you can push things quite far in terms of political messaging. And also a well-timed slap on the wrist from the EBU can get you into the headlines on the day of competition, which might be crucial. I think that stopping Salvador from wearing his SOS REFUGEES jumper backstage was a poor move on the part of the EBU – and that it allowed the Portuguese delegation to capitalise on their singer being censored when trying to raise awareness of an issue that shames all of Europe.

The Icelandic and international pressure to withdraw from the competition is real and understandable. It’s incredibly uncomfortable to have the contest adjacent to the occupation of Palestine but it’s outrageous not to be able to talk about it. By bringing along their own semi-independent and possibly-previously-fake media outlet ‘Iceland Music News’, Hatari have been able to amplify messages from activists on behalf of Palestine in between contributing to their own myth-making.

A Question Of Lust, A Question Of Trust

As a delegation, you can only walk a tightrope like being political at Eurovision when everyone trusts one another. One of the things that people don’t often realise about BDSM is that it’s about trust and interdependence in action. You trust each other with your bodies, trust in each other’s vulnerabilities and needs. You acknowledge that you’re dependent on each other and that interdependence is what unlocks the experience.

While the band aren’t actually lifestyle BDSM folks, something that is very obvious is how much the whole Hatari ensemble trust and rely on each other. In their media clips, they behave like a very close and long-running improv troupe. There are levels of trust – Matti and Klemens trust each other physically and artistically, otherwise their effortless stage interplay and offstage demeanour wouldn’t work. Einar trusts that Matti and Klemens will hold the front of the stage so he can menace people from the back, and they trust that he’ll continue to supply the rhythm. Astros, Solbjort and Andrean trust in the music and the band trust in their physical commitment to the piece.

What’s been interesting to see throughout the Icelandic campaign is how much the wider delegation trust in the plan. Everyone all the way up to the Head of Delegation is part of a secret gameplan – and they’re enjoying themselves tremendously. They’ve all spent most of the Eurovision fortnight wearing Team Hatari tracksuits. How do you get that level of buy-in from a team? How does a delegation achieve this?

Eurovision has also given the group a platform to complete onboarding of delegations into the narrative, from Australia’s Kate Miller-Heidke proclaiming on video that she is drawn to and repelled by the group in equal measure, to Darude from Finland freely admitting the political nature of his entry to the contest.

Yeah, But What Does It All Mean?

What does any of this mean? Life is a relentless scam. Escape from the system is impossible. But revolution starts with imagining another way.

Selling Out, Then What?

Regardless of the result, participating in Eurovision has given Hatari an opportunity to go from a critically acclaimed and award-winning cult band in a highly concentrated local scene to a phenomenon playing their game on a much larger scale while gathering seriously committed international fans.

What remains is how far this game now develops – both for the rest of the contest week and for the future. What does selling out look like when it takes you 4 years to get round to selling merchandise on your website? What will the outcome of their promised documentary filmed in Israel be exactly? Will the promised album release come in September? Will they do the worldwide festival circuit? Or will they just simply vanish and reappear in 18 months as children’s TV presenters?

We are on this journey, along for the ride with Hatari in the driver’s seat, and it’s going to be a lot of fun arriving at the final destination.

Many thanks to Ásta Eymundsdóttir for the additional research and Rob Holley for many, many useful conversations.

Someone clearly bought a dictionary….

I really am loving how every Eurovision ‘journalist’ is continually championing this rubbish in the name of ‘art’. It’s Salvador all over again, but at least he was talented. This is a bunch of rich kids trying to be edgy because they don’t like Daddy’s government job.

Wow, Ellie, fabulous article. Really comprehensive, and gives me lots of trails to investigate. Thanks for the insights that are helping me understand and maybe enjoy Hatari!

Sublime piece of writing, really getting under the skin of Hatari.

The fact that all this needs to be explained goes to show why I can’t see them doing all that well tonight – it will just come across as loud and aggressive to the average viewer.

This is art for the modern era. integrated, versatile, and linked to the political nightmare that is our current reality. Great article. Let us know if and where and how we can support Hatari.

I think I gonna save up a little and buy a t-shirt from Hatari mysterious but not quite impenetrable website. Or maybe just spam everybody around me with this kick in the eye “band”. Politically there are a little chances that anything/anyone this articulated and strong comes play a defining role in the global mess. But culturally at least we have some. Love light and Hatari.

I’m far from this music style but I fully followed the path from shock to agitation that she describes.

The vision of a few videos from Hatari shows yes that’s a scam and a game. It’s interesting and funny. Very Eurovision (remember Verka Serdyuchka from Ukraine, I had the same feeling).

Congratulations to the band!

I love them.

A French fan.

Thank you Ellie!

That was beautiful.

Nice analysis Ellie. I would only be surprised if Hatari denied anything you wrote but I’m 99.9% sure you hit all the nails on the head. If only the naysayers like Mawnck who don’t get the joke could understand that the joke that’s been created was bait and they’ve inadvertently (by ill education and intolerance) volunteered to become the butt and a stooge. Hatari are my most favourite type of dissent. Peaceful and smart and the sharpest knife that cuts the enemies ignorance and hate open for everyone to see.