How We Decide The Winner

To a regular viewer of the Eurovision Song Contest, the voting system in place for Junior Eurovision is incredibly familiar. The voting is be revealed in two parts. Firstly there will be spokespeople from each country presenting how their country voted. This part of the vote has been decided by a jury of five people. Three of those people are music industry professionals and two of those are aged ten to fifteen.

They even give douze points to their favourite. So much, so similar.

The last half of the points is presented in one big block, but isn’t made up from a combination of the cross-continental televote. Instead it comes from an online vote. The way the online vote works is that from the Friday before the show until the show begins visitors to junioreurovision.tv can access a special voting page. Here they can cast their vote with two unique differences. They can only vote for between three to five songs and can vote for the country they are voting from.

Voting re-opens after all songs have been performed for a window of about fifteen minute and these votes are added to those previously cast. The final results are converted into points based on the percentages of votes cast.

Junior Eurovision in the last decade has been a source of innovation, a place for the EBU to trial and test new ideas, with kids’ juries, juries in the arena, and the now steadfast 50/50 voting split which began in 2008. Online voting is definitely a creative step into the 21st century, but how does this compare in practice to a good old televote?

Strengths

One Time That Fits All

Junior Eurovision, this year with a record twenty entrants, covers vast distances from east to west from Ireland and Portugal to Kazakhstan and Australia.

The chance of finding a timezone capable of staging a televote for a children’s television show? Pretty much as close to zero as possible.

One key benefit of the online vote is that it starts from two days before the show, meaning there is ample time wherever you are in the world to click on the link and cast your vote. This is great for getting potential viewers engaged even before the show broadcasts and extends the reach that Junior Eurovision can have.

There’s also another benefit in that it means Junior Eurovision can reach out beyond the twenty countries that compete this year. Countries such as Spain and Croatia, previous winners that no longer take part, can still give their Junior Eurovision fans an opportunity to engage and vote for their favourites.

Online Voting Doesn’t Cost A Thing

Televoting prices across Europe range quite a surprisingly large amount depending on which country you are voting in, I’ve seen prices in Denmark at around ten eurocents but Malta is ten times more than that.

Cost can be a barrier to getting your democratic voice heard. A free-to-use platform should in theory encourage a more representative result.

Another benefit is that it can be linked in very easily from social media. Online voting is easier because all you have to do to vote is follow a shared link. Televoting requires you to remember or write down the number, come off whatever app your are using and head into your SMS or call system. That extra step is also a small hurdle that some people would not cross.

Reducing The Power Of The ‘Bloc’

With online voting there comes the extra possibility to limit the number of votes given. The lower limit of 3 and upper limit of 5 seem arbitary at first glance, but do seem to be completely sensible limits.

Forever it has seemed that the Eurovision Song Contest has been dogged by political voting, regional voting, diaspora voting. Whatever one calls it, people always find ways to complain that X country always votes for country Y.

In Junior Eurovision one may vote for their own country. They may also vote for a country they come from or border or any of that. But they have to make at least one other choice. Excepting those young people with more passports than one can fit into your Ryanair hand luggage at least one of those votes has to be for a different country.

The beauty here is that for every vote for your own country, or your diaspora country or whatever – you also need to make a vote for somebody else that you want to support. By spreading out this love we can make the Junior Eurovision voting more reflective of who people believe to be best.

Weaknesses

The Voting For Yourself

One of the dilemmas that this voting system creates is the ability to vote for your own country. One big fear of such a system is that it means countries with far higher populations will score higher.

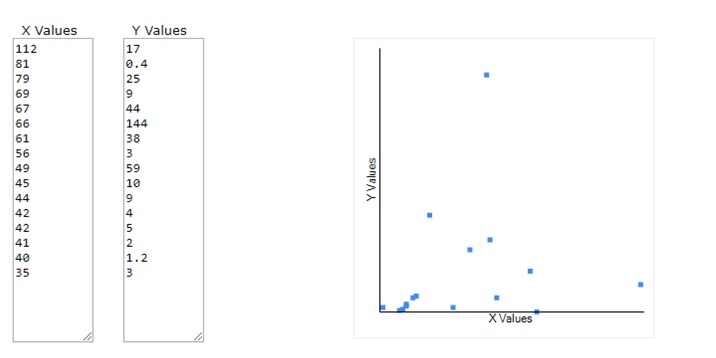

The data from last year however does not suggest that countries with a bigger population do better in the online vote. The below graph plots online voting score (X value) against population (Y value) and you can see relatively little correlation between the two. Russia, the eventual winner, only placed sixth in the online vote despite being over 100 times the population of Malta, the online vote’s runner-up.

The above graph plots population against online vote from Junior Eurovision 2017. The correlation is very weak between both variables.

It is likely more important how popular Junior Eurovision is in the country that you are watching in. This is especially true with many larger nations sidelining the show to dedicated children’s channels with a smaller audience.

I have previously been on the ground in Malta for both their Junior Eurovision hostings and I can safely say that no collective country is more Junior Eurovision mad than the little Mediterreanean island. The Dutch boy band Fource dominated online voting, but had at their disposal a big following from Dutch TV and on social media after plenty of airtime following their journey to Tbilisi.

Even before hearing the song many Junior Eurovision fans are tipping Poland’s chances of success. Poland’s representative Roksana Węgiel’s Instagram followers total over a whopping 242,000. By being able to vote for your own country allows all of Roksana’s followers to support her in her quest for the title.

50/50 Voting In Name Only

One potential balancing act to this though is the nature of the online vote. Each time you vote you have to choose between three to five countries. The results of this is that your voice is spread across a larger spread of options. This voting is not ranked, so your favourite song would get the same number of votes as your third, fourth or fifth favourite when you vote. This makes more songs cluster in votes around the middle of the scoreboard.

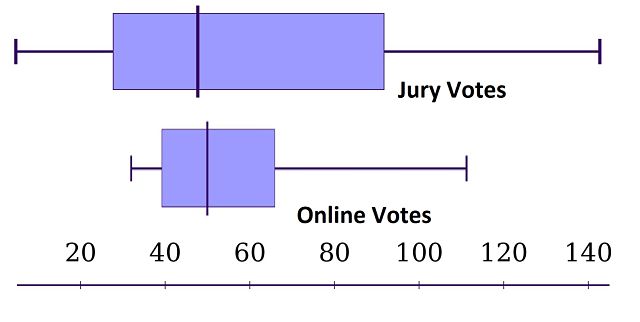

The below box-and-whisker-plot shows the differences between last year’s jury voting and online voting. The jury votes have a much wider range of scores – bottom placed Cyprus scored 5 points and jury winner Georgia took 143. The online vote scores ranged from 35 to 112.

The box and whisker plot shows the much smaller range of scoring with the online vote compared to the jury vote

This is far from likely to be a one-year trend, and as Melodifestivalen fans will know the App system used in recent years has led to a similarly small spread of votes from the public. It may be 50/50 in terms of the total number of votes, but the reality is that the jury show is significantly more important.

It’s also really boring. Even those without A grades in maths it’s easy to recognise that last year there was no chance of Malta and the Netherlands catching Russia for the victory, there wasn’t enough points left on the table. The whole idea of the modern presentation of jury and televotes in the Eurovision Song Contest is that it heightens the suspense and the drama, always ending on a cliffhanger. However in the Eurovision Song Contest usually it is the televotes that are more diverse than the jury results, which makes that last reveal exciting. In Junior Eurovision more often than not the final minutes of voting will appear as a damp squib.

Does the performance actually matter?

With a voting system giving more variance to the jury vote during the Saturday rehearsal, and the ability to vote for your own country – how much is the Sunday performance worth on the final leaderboard?

Due to the fact that online voting is open before the voting period is very possible we could have a winner of the show decided before the sun rises in Minsk on Sunday morning. In one sense there is the safety net for the children that not everything is relying on one pressure-filled performance.

However we all know through Eurovision history there are songs that work really well on radio or music video format that just don’t translate across to the stage. Such songs have an advantage in modern Junior Eurovision, and I question if that change in direction is a positive step. A song winning on November 25th that doesn’t work well on the stage might open the question on this balance again.

Opportunities For Improvement

Rehearsal Clips Are The Real Deal

One issue with the online vote being taken before the show is that the performances used for people to choose from are taken from the rehearsal footage.

On the official YouTube channel from last year you can find one performance of the full song from the first rehearsal recorded from cameras not used in the TV broadcast. In addition there is a one minute section from the second rehearsal taken from the TV broadcast feed, and when viewers log in to vote they are shown a short recap of all the competing entries.

The problem is that they are all rehearsal footage. We are watching and judging practice performances. Camera shots show empty arenas and metal barriers rather than the rainbow cacophony of colour a Junior Eurovision audience creates.

It somehow feels wrong that a practice performance should be used for judging a show. I fully recognise that there isn’t another alternative with the earlier online vote (it is a more level playing field than showing music video clips would be, for example), but for both the kids and the voters using these performances is clunky at best, with the performances not yet tweaked to 100%.

Where an opportunity could lie is to change which performance is voted on, by reducing the voting window prior to the show to 24 hours. This means that the show rehearsal on which the Jury bases its decisions on is also open to the public to make its judgement on. There is the concern that it would add pressure to the performer, but it also ensures the artist has had the chance to take advantage of the more informal rehearsal period to tweak the staging and camera work away from the many eyes of the world.

The Contest Where Online Voting Failed

Last year in Tbilisi was, and is remembered as, ’the Contest where online voting failed’. As soon as the voting window was open after the show social media erupted with fans worldwide unable to log in and cast their votes.

I was one of those back home frantically refreshing only to be greeted with blank screens ad finitium.

Voting not possible for me after the live show in Tbilisi last year

Yes, the online vote that was recorded was deemed ’valid’ by the EBU, and plenty of votes were recorded before the show itself. However the comments during the show of ‘we have experience some problems with the online voting, but we are checking’ was never going to be enough to appease viewers at home. It appeared like it was an inconvenience, when instead the voting itself should be the competition’s most sacred factor.

While one can argue it is no surprise to see the same system return for 2018, the EBU’s press release about the format does not highlight any measures made to ensure no problems arise this year.

There will be question marks about whether this will happen again or not this until the voting window opens on Sunday November 25th. Clearly the opportunity here is to demonstrate that they have learned from previous issues and can reassure viewers of the integrity of the voting system, as well as delegations and artists in Minsk more confident of its reliability.

In Conclusion

The Junior Eurovision Song Contest is a place where things should be tested and new innovations should be trialled. Online voting is a revolutionary idea. It is a step in a new brave direction. And mistakes are going to happen in using new technology. I don’t object to taking those risks.

Were these puzzled looks from the green room our artists in bemusement at being unable to vote? (Photo: Thomas Hanses, EBU)

The impression the voting system has on the artists involved is my biggest concern. I am thirty years old now. Gone is much of my idealism about fairness and equality. Maturity has helped me understand how much the world works and how much people make decisions with hands tied behind their back.

I didn’t think like that as a teenager, you probably didn’t either. As we age human beings look to rationalise the ”unfair” around them. Younger children are more likely to create a fairness that is equal, and as we age we allow social conditions, such as the value of somebody, decide who gets what rewards.

Online voting allows those with more home support to flourish on the leaderboard. Judging before the live show makes it harder for your performance to sway opinion, so the young people on stage may give the performance of their life on Sunday November 25th and it may make zero impact on the final vote.

Yes, we should use Junior Eurovision for innovation at all levels. However it is a show aimed at younger people, and younger people demand a higher level of fairness and equality than anybody else.