You Can Win In Your Own Country

While it might actually be more recent than many remember (Poland at Junior Eurovision 2019), it might be prudent to remember that France securing their 3rd win in four years at Junior Eurovision is more evidence that a host nation can win the Song Contest. The 2019 victory for Poland came with a smash hit song at a time when Polish TV viewers dominated the viewing demographics. France’s 1.2 million viewers were larger than many but nowhere near close enough to guarantee victory. In total, just shy of 30% of all voters at Junior Eurovision cast a vote for France, meaning we can assume plenty of votes from around the continent as they won the jury and public vote.

Don’t rule out Sweden’s eighth victory in Malmö just because it’s SVT’s back yard.

Opening Isn’t Cursed

Spain’s randomly drawn running order of first, saw many of their supporters groan. ‘Loviu’ was a song considered winning potential as we arrived in Nice, and with no opener at Junior Eurovision ever placing higher than fourth previously, some saw that as the ceiling for this entry, especially as France and the Netherlands randomly drew strong second-half slots.

Instead, Spain placed in a comfortable second position, with third place from juries and 2nd place from the online vote, a very decent showing and one that hopefully serves as a reminder that running order in Junior Eurovision is less significant. Could Spain have won? If Spain drew 16th and France drew 2nd there could be a situation where that 27-point swing would have occurred, but that would have been unlikely, especially at Junior Eurovision where juries have more weighting and voting opens before the show.

We all have a mindset of overplaying the significance of running order (me included) but let’s bookmark this one for the future.

Money Talked

I wrote about the Haves and Have Nots at Junior Eurovision before the show was broadcast, taking a gamble by naming the only bunch of countries that were in the mix for victory, and those that were going to be at the foot of the table.

Those predictions ended up being even worse than we had feared. The previously unfancied Polish song managed to move itself up into a sixth position, no doubt helped by copious amounts of budget burning pyro, and fan favourite North Macedonia stuttered themselves into yet another 12th place finish at Junior Eurovision.

We have a competition that is becoming further and further divided by the financial resources and efforts of broadcasters that I am sure we all find rather uncomfortable for a show for children. Solutions are needed. Backing dancers supplied by the host broadcaster? Extra tax on the rich to distribute to the poor? Options of delegations from smaller nations and broadcasters to say at less exclusive hotels in the host city?

In any case, let me give a shout out here for Albania, Viola Gjyzeli’s vocals took ‘Bota ime’ to 8th place on Sunday afternoon. Realistically for Albania such a strong result is the equivalent of winning.

Youth Empowerment

The United Kingdom’s fourth place is a job well done, but it was regardless of the result. It was a perfect marriage of a top-drawer creative concept with influence from the young people selected to make it fit their own styles and vision. Few come to Junior Eurovision to try out technology that has never been done before in an EBU context, and few do so with children involved throughout the creative process. The UK’s delegation decided to do just that.

Every broadcaster should take a nosey at what the BBC brought to Junior Eurovision this year and should take note.

As discussed on the final podcast of the season, there are some with critique that Armenia took their concept too far to be one dictated by adults rather than being appropriately child-led and appropriate for the kids involved. I don’t know enough about the journey of the Armenian entry into Junior Eurovision this year to comment, but it did take them to third place.

The Fresh Sounds of Youth

Armenia securing their tenth Junior Eurovision podium at the Nice Contest proves how much of a powerhouse this nation is at Junior. The package fronted by Yan Girls to Yerevan had musical production that blew away the other competitors and took Junior Eurovision into K-pop territory with ease. I suspect it won’t be the last K-pop composition in this show.

I do think that this might be the last time the EDM sound makes an appearance. The Dutch Junior Eurovision entry gained momentum in the press bubble all week and has become the first song of Junior Eurovision 2023 to top one million streams on Spotify in the aftermath of Sunday afternoon. But the eventual finish of seventh place, especially with ‘only’ a fifth place from the online vote, is less than the expectations for many going into the Palais Nikaïa on Sunday.

I think the answer is simple. The press bubble is made up of adults who have memories of the EDM sound from their youth (or, at the very worst, from a time of fewer grey hairs), who would feel that this sound would be perfect for the kids of today. The music tastes of the 9-14 age group change rapidly and this genre, a sound they may have recollections of from preschool, is dated to their modern ears. Expect more tracks like what Armenia and the United Kingdom brought to Nice wherever we end up next year.

We Will Always Be Discussing Age

The term Junior is a loaded term. We all have a preconception of what is appropriate for 9- to 14-year-olds, and we come to the show often with those biases firmly implanted. From the styles of music to the style of outfits (note, almost every critique about outfit appropriateness is about what girls are wearing), Junior Eurovision is always going to be a difficult thing to get that balance right. For what it’s worth I’d argue Junior Eurovision is in a far better place now than it was a decade ago. We have a strong bunch of competing nations and an array of artists that I think continue setting the bar higher.

But while the age range is 9-14 I think we’ll always have conversations about what is appropriate or not. It is through these ages that today’s generation goes through their most change. Is it right that 14-year-old Yulan Law belted out ‘Stronger’ just before tiny 9-year-old Anastasia Dymyd sang her little ditty ‘Kvitka’? How can viewers fairly compare entries that are so diverse in maturity?

What Are The Press For?

With journalists accredited for Junior Eurovision unable to see any individual country rehearsals this year, the EBU allowed access to the press centre at the Palais Nikaïa late on Friday afternoon.

The problem? Voting was set to open that evening. Cue logistical nightmares for delegations wanting to get their stories out in good time, journalists wanting content, and the difficulty in finding a safe space suitable for our young performers. Quite a few interviews happened outside this year which may work in Nice but would have been a disaster in most of the continent in November.

Even if the press can’t get to see rehearsals, the easiest solution in my eyes would be to have a press centre open earlier, regardless of rehearsal coverage, so everybody has a safe working space, and it’s easier for kids to divide up their press work to a press location rather than never feeling able to rest.

We Don’t Know Where We Will Be Yet

At Junior Eurovision nowadays the hosting situation is that the winner of the show gets first refusal to host, and the obligation is less than at the Song Contest in May. France has now hosted in 2021 and 2023 and with a Paris Olympics in 2024 a fair few commentators are suggesting that the extra workload on the French broadcaster may mean that priorities are already made that give no room to co-ordinate another major event.

While there was much French bravado at the winner’s press conference in Nice about even gunning for a Eurovision victory in Malmö, the morning after the broadcaster noted that “many countries” are interested in hosting this show.

And I assume that Spain will be the nation most interested to host, and, after finishing 2nd, would easily be able to argue for bringing the first Eurovision event to Spain since 1969.

My uneducated opinion is that, if French TV is able to find a city that is willing to partner with them on agreeable terms to host, then they will. However I expect Spain will be quietly sounding out cities of their own if they need to jump in to organise the show.

It seems obvious to say Benidorm, given it will be low season and their recent partnership in organising the Spanish national final, but let me also point out that the Gran Canaria Arena can take around 10,000 fans. Just saying.

A Secret Platform

Yes, the Palais Nikaïa is a smaller venue than a Eurovision Song Contest, but there’s one element from that stage I’d love to transfer for the Eurovision Song Contest too. The accordion-style lift hidden beneath the middle of the stage.

It’s a simple design, but it had sufficient height, width and depth to make an inexpensive impression by lifting up an artist above the stage, and the LED border around it gave lovely framing.

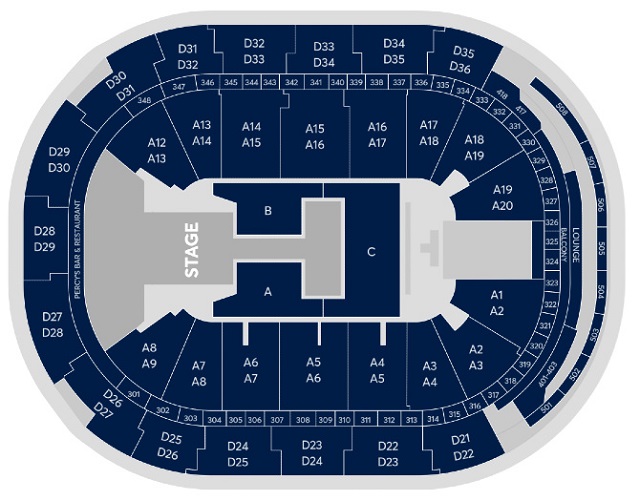

The floor plan for tickets at the Malmö Arena for Eurovision 2024

The floor plan for Malmö has a very tempting catwalk with a wide stage area at its base – that’s where I’d love to elevate the artists in May. It’s not like Malmö has any experience of having a hidden stage element that rises out from the secondary stage at a previous Contest. Oh…

Flags. Just Ban Flags.

Hear me out on this one. There was drama outside the arena for numerous Eurovision fans who had come along to Junior Eurovision with flags that they had to throw away. They were too large or were on sticks and I’m sure many of you who have attended Eurovision contests in recent years will know the drill. At the end of the show families were scurrying through the bins to try and retrieve said flags in a sorry situation. Even though security was hot on checking flags on entry, numerous large flags did make it through to the arena, including a couple of Nagorno-Karabakh flags with the significant Armenian diaspora.

But there was an interesting quirk which was a first for me at a Eurovision event. The local OGAE France had been summoned in to distribute flags to fans arriving for the show. Sadly supply did not cover demand for this but it gave me an idea.

Firstly, ban the bringing in of all flags. Secondly, have a system where inside the arena each person is able to pick up one flag from a dedicated stall (more if they choose to pay for it), and fans can also pre-order a certain flag if they so wish. Will require some logistics and warehouse facilities to store the flags again throughout the season, but if it is so important to not have oversize or inappropriate flags then I can see this as a workable solution.

Maybe try it out at Junior next year and see if it works.

The Show’s Slow Pacing

Between the sixteen competing songs, we had three different breaks in the running order, between songs 4 and 5, 7 and 8, and 11 and 12. Now some of the stage set-up may have required this, but what was thrown in during these windows was not good television for this target audience. Interviewing the Junior Eurovision artists in the green room was tedious, especially for those who struggled to answer in English. Part of the new Safeguarding Policy points out that kids shouldn’t be doing stunts they “aren’t equipped to do” and I could argue this was an unnecessary stress for our young performers.

Even if these ad breaks were a last-minute bit of filler, they weren’t the only time when the hosts blathered on far too long – it took us over 12 minutes to go from Te Deum to Spain’s opening number, and we could have easily have skipped a running order reveal and the over-explanations given throughout. Maybe it is worth investing in some video material that can be used in such scenarios to make the show pop and keep up the tempo more.

The Awkwardness of the Voting Reveal

You may be aware that one of my pet hates is the way modern Eurovision reveals the points at the end of the voting sequence, but the show on Sunday was a particularly poor version of it. There have been reports of tears backstage, cameras lingering on acts that were already out of contention and a final split screen between France and Spain that was almost two minutes in length. It is needless that every act needs to be in camera shot while their votes are revealed. The safeguarding of the performers should trump the needs of live television.

I think it would be prudent to look at options for how Junior Eurovision could present this in a different way in the future. Some ideas bouncing around the press centre after the Contest included only revealing a top 10, moving more quickly through the bottom half of the scoreboard, presenting the points of the public vote for the winner with a fast-moving bar chart (a la Denmark’s MGP) and ensuring tighter control over which shots are visible on camera (ensuring happy children is the priority, rather than live reactions).

Many pros and cons to all the ideas practically, but Junior Eurovision is the place for such experimentation to take place. I will be dismayed if no changes are made to this by twelve months’ time.

And that’s our twelve lessons to takek away from Junior Eurovision 2023. Do you have any more? Add them into the comments below.

Thank you for such a detailed overview of the show, with its usual pros and cons in terms of content and production. JESC has always been seen as a test field for changes that eventually will be added into ESC, like the 12-point announcement. I would like to clarify 2 of your points made in the article:

– Delegation money: smaller broadcasters like ETV, RTSH or TG4 are trying their best within their budgets to bring decent acts, irrespective of their result. Hope that will be an example for RÚV, LRT or YLE to join soon.

In 2013 Kyiv offered dancers and props for other JESC acts: only San Marino and Azerbaijan accepted those. I wonder why this measure has been discontinued.

– Age appropriateness: after much discussion, I might agree with the view of Lauren Layfield, from the CBBC. She sold the JESC in an interview as a show where you could see all types of music, instead of a bunch of “teen-poppy” acts.

Diversity is key here: the British girl group, a rocky Italian ballad in a duet, Dutch EDM, (underrepresented in ESC) Spanish pop rock, child ethnic pop from Ukraine, etc. I’m no one to discuss about the outfits either. Why can’t an Estonian act dress up like Wednesday Addams and sing about friendship?

About the 2024 venue, I also hope TVE might take charge for once. Valencia is highly rumoured, even though Tenerife is better connected all over Europe. Still too soon to speculate, though.