“Well, um, because no one else seems to be.”

These were the first words that Zoë Jay, a researcher at the University of Helsinki, gave as we sat down to talk about her latest research. My first question was the obvious one, why would one research this niche topic within a niche topic?

That topic was Junior Eurovision.

“There just wasn’t anything that looked at it as an event in its own right,” Zoë continued. “When other academics mention it, they sort of mention that, oh, Junior Eurovision also exists, so you get footnotes occasionally recognizing it. But no one has done a real study.”

As an academic Zoë’s background is within international politics. Her previous work has written about contrasting conceptions of the European Court of Human Rights, national identity across Europe and yes, the odd article that shines a light on the Eurovision Song Contest. Yet the 19th October 2023 saw the publication of “Be Creative, Be Friends and Share Cultural Experiences”, a deep dive behind Junior Eurovision and the subtle political undertones to this most non-political of events, which Zoë explained:

“At Junior Eurovision, we have this additional layer of assuming that children are innocent and need to be protected from the nasty, dangerous world of adult politics and should be allowed to have fun. We’ve got these particular societal understandings about what children are, what they should be doing and what childhood should look like, which are obviously not how a lot of children live their lives in reality.”

“It sort of says this interesting stuff about what we consider political or not because you get these really overtly political messages in songs and we all sit there going, oh, this is so cute. Children are singing little songs about saving the planet. Everything’s going to be okay. So it’s got this sentimental function to it where adults feel really nostalgic, safe and happy because the children make everything seem cute and fun.”

Lyrical Messages of the Past

Zoë’s paper begins by referencing the lyrics of the 2019 Junior Eurovision ‘Superhero’, Viki Gabor’s pop song that masked an undertone about how essential it was for listeners to unite to save the world from climate disaster. That entry was one of many that year, at the peak of Greta Thunberg’s media breakthrough, that tackled the climate crisis.

“It’s not political in the sense that it’s existential,” explains Zoë, “it’s about humans and other living creatures surviving. But it’s also political in terms of how governments and countries respond. Or at a deeper level, the very overwhelming message from these children is that they are not responding and they have to, the children are singing things like time is running out and we have to act.”

Another example that Zoë lifts up is Chanel Dilecta’s ‘Bla Bla Bla’ from Yerevan 2022. Performed from the perspective of the child, Italy’s performer in Yerevan criticised adults in the world for their infectivity in handling the issues of the day. Zoë explains that “adults constantly put the responsibility on them [children] to fix our problems”, noting how adults know that “children are clearly aware of the failure of governments to do stuff that’s essential.” ‘Bla Bla Bla’ was a prime example of this, where adult songwriters created the number about that issue all for 13-year-old Chanel to sing.

Research into international politics and its use of and impact on children that Zoë Jay has looked into rarely delves deep into events as fluffy as Junior Eurovision should be. Instead, it is the heavy stuff, war zones and children in activism roles, the “traditional high politics” of the day, which is better understood. Junior Eurovision is a whole different microenvironment, the complete opposite of the one usually studied.

Ukraine’s entry last year is a rare example where the words collided. Zlata Dziunka’s self-written entry ‘Nezlamna (Unbreakable)’. A powerful song calling out for divine help to save young people dying in war. And not just any war, the war affected her country at this point in time, influencing a music video of children hiding in a church basement. Zoë notes that Zlata was able to speak in interviews about her presence, even as a young artist, as a way of contributing to the war effort. Such a direct acknowledgement of political significance, Zoë believes, is something that “adults are not allowed to do” within the normal confines of the contest, at least not without “careful diplomacy”.

What The 2023 Contestants Are Saying

While this year’s sixteen Junior Eurovision participants do not offer numerous songs on the same topic, there are themes which appear throughout the competitive songs which showcase the stories of young people. Ukraine’s entry this year, performed by 9-year-old Anastasia Dymyd, may have the production feel of an innocent children’s song, but within the performance is the repeated line “stop the tragedy”. “Contextually relevant,” Zoë explains, “as a clear reminder to people that war still exists.”

This year’s Italian entry ‘Un Mondo Giusto’ (translated: ‘A Just World’) thematically is the sequel to Italy’s composition last year. The two singers Melissa and Ranya present a world where one day the world will be fairer, and freer for people on Earth. However, in the story of the song it is not like that today, with Zoë noting the first verse lyric “Il mondo è in mano a chi ne fa le regole” (Translation: “The world is in the hands of those who make the rules”) as another nod to the comforting storytelling of young people wishing for a brighter future than what we have today.

Beyond these there is a small window into the possible loneliness that young people feel in 2023, shown by both Poland’s ‘I Just Need A Friend’ and Portugal’s ‘Where I Belong’. The latter of these songs Zoë picks out because of the way artist Júlia Machedo, who grew up in New Jersey but moved to Portugal aged 12, uses her song to discuss struggling to fit into a new environment. This story may be personal to her but also can lift up similar emotions for the increasing number of young people living in new towns, cities and countries across Europe.

The opposite of loneliness in this year’s Junior Eurovision is also the theme of inclusion, a theme very visible in both the Spanish and German songs this year. Spain’s multi-lingual chorus is a classic way of ensuring everybody can understand your song across borders, while Fia from Germany uses sign language to communicate the message of her song ‘Ohne Worte’ (Translation: ‘Without Words’) to a wider audience.

Entering The Juxtapolitical Space

Noting the lyrical trends of Junior Eurovision songs, while deeply fascinating, isn’t necessarily enough to justify academic literature. What does justify deep critique though is understanding why Junior Eurovision fills in this space in society, and brings songs of such themes year after year. Zoë Jay takes inspiration from the work of esteemed academic Lauren Berlant to explore the framework that Junior Eurovision exists within.

Lauren Berlant describes a definition of the word genre to be “provide an affective expectation of the experience”. The genre of something is therefore what the viewing public anticipates the product or performance to be. With this Lauren Berlant explains that a “common historical experience” between the viewers creates the genre space that any event resides in.

Zoë argues in her article that Eurovision and Junior Eurovision are “sustained by different genres” and therefore there are “slightly different expectations and emotional attachments” to each of the EBU’s Song Contests. While Eurovision and Junior Eurovision share multi-national entertainment spaces, they differ because of the “adult conceptions of childhood” that frame the contest. What is expected from Junior Eurovision is a competition that is more “wholesome”, where the songs are more “adorable” and the artists present themselves in the way adults nostalgically expect children to describe their childhood as – fun.

With this, Zoë notes that there is a “political unconsciousness” that is vital to the accepted image of children which is a key difference between Eurovision and Junior Eurovision. Yes, the Eurovision Song Contest is a non-political event, but the way politics interweaves itself into the programming, production and points scoring is well-studied and known. Instead at Junior the non-political element is obvious because of the show’s age bracket (different than at the Eurovision Song Contest, there is no particularly no political song rule within Junior Eurovision). The ‘politics’ on show at Junior Eurovision has a very different look and feel than the Big Brother competition.

“By assuming children are inherently non-political and creating events for them based around notions of fun rather than competition…adults do not (want to) see or acknowledge children’s political articulations when they occur because doing so draws attention to their own failures to have or provide peaceful, carefree childhoods.”

And this is where there is a difference in how politics is expressed within the songs that compete within Junior Eurovision. The themes may touch on political issues, and a significant number of artists sing about difficult topics. but rarely are any of those political viewpoints divisive. The songs about climate change plead for change, for the next generation to make noise and make a difference, but they aren’t demanding specifics about greenhouse gas emissions or direct policies to stop deforestation. There’s nothing in any Junior Eurovision song that wouldn’t be out of place on a school curriculum or differ from the views of the broadcaster. A Ukrainian act at Junior Eurovision may directly or indirectly make it clear the current conflict is part of the performance, but the messaging holds back on specific acts or political decisions – the level of detail shown is what we adults would be comfortable with our children doing.

In this sense, the rationale by Zoë Jay is that Junior Eurovision exists in the juxtapolitical – “flourishing in the proximity to the political”. While there may be depth and potentially tough issues that come from Junior Eurovision songs, they stay on the outskirts of the hard facts and tough decision-making needed to take the world forward. The genre space that Junior Eurovision exists within is a juxtapolitical one.

The Juxtapolitical Slice Away From Competition

Part of Junior Eurovision’s success in recent years has been due to how certain broadcasters have found the show a suitable platform to further their own agenda, which has varying levels of the juxtapolitical. While not present in Nice, Kazakhstan’s broadcaster was open about the benefits that taking part in Junior Eurovision gave to furthering their desire to be not just a greater part of the EBU, but also a more accepted part of Europe for the developing nation.

The participation of both TG4 for Ireland and, until recently, S4C from Wales in the contest demonstrates a big, international platform for each broadcaster to showcase their national languages to a wider audience. And to do this with the next generation, demonstrating how the national language can spread beyond the nation’s borders, is a great tool to promote the resurgence of these national languages domestically. This is not a political goal from the broadcaster, but instead, this promotion exists juxtapolitically to strengthen the status of these languages domestically.

In addition to all the participants from the different broadcasters, you also have at Junior Eurovision one more musical number for the performing acts, a common song. These common songs are prime examples of the “non-political politics” that is on point for the genre of Junior Eurovision, with themes about unity, friendship and empowerment commonplace. These songs are commissioned by each show’s organising broadcaster, designed to fit all the contestants, and as such they offer heightened examples of “adults’ sentimentality” that is projected upon the next generation.

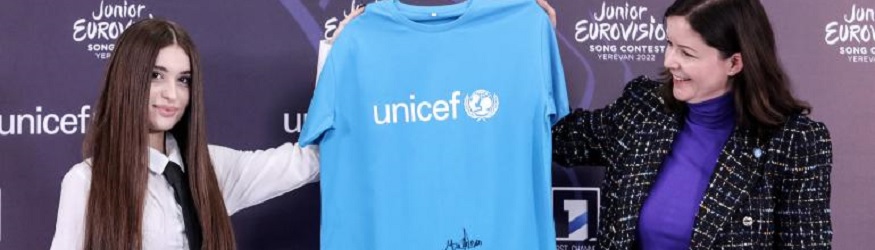

Many editions of Junior Eurovision have seen the common song be produced in collaboration with UNICEF, including using images of children in need on the screen alongside the song and fundraising for UNICEF through song proceeds. Furthermore, last year in Yerevan one of the press conferences at Junior Eurovision was to showcase that 2021 winner Maléna was a UNICEF children’s ambassador. Now UNICEF as an organisation states in its mission that it is non-political, yet UNICEF projects have been linked to political influence and UNICEF at times takes policy stances that create political division between itself and other nations on Earth.

UNICEF is a great example of an organisation that exists in a space where adults are comfortable with young people working with. The goals of UNICEF, such as protecting the rights of the child and helping children to survive, thrive and fulfil their potential, are goals that do not rock the boat in a Junior Eurovision context. However, Zoë Jay points out that this “ties the performers not only to European integration but also to the global liberal international order and to the paternalism and imperialism inherent in UN-led development programs”.

Even at this edition in Nice, we will see the flavours of adults’ hopeful projections upon the next generation shine bright. Alexandra Redde-Amiel from the French broadcaster notes that indeed the inspiration from how young people have presented themselves in recent Junior Eurovision Song Contests has been inspiration for this year’s theme, “Heroes”.

“Some serious topics like the environmental theme were extremely present in many songs of the last contest, and the children are the real Heroes of tomorrow, and they are the ones who have the solutions. So we wanted to let them empower themselves!”

At every level within Junior Eurovision there is demonstrated this adult projection of acceptable agency for our next generation.

They Can Be Heroes

This does not belittle what it is that the children actually can achieve through this contest of song. The majority of children have a positive opinion of the contest, and whatever degrees of freedom those children have on their song topics and presentation through Junior Eurovision, time and time again we see adults comforted by their great ability.

What we have learnt through Zoë Jay’s research is that Junior Eurovision sits in a rather unique niche and one where the combination of the words Junior and Eurovision create a world with very defined set of expectations for the viewing audience.

The young performers at the Song Contest often perform numbers that exemplify what well-meaning adults want the next generation to sing about – brighter futures, saving the planet and putting right the wrongs of today. That said, these songs are not practical activism and are nurtured in the Junior Eurovision environment, devoid of rebellious teenage defiance.

The end result is a competition that showcases very strong values, those of unity and togetherness, and one that so is achingly non-political that itself makes it a platform for the softest of political gestures.

Nothing at Junior Eurovision is there to rock the boat, but it is there to raise a voice.

To end, I put it to Zoë Jay if there was anything that she believes should change at Junior Eurovision in the future. One idea was to review the values that Junior Eurovision has on a regular basis, to ask ourselves about the environment we are putting children into and what those values do in curating the experience. The values of a Contest for our next generation with a young target audience may change rapidly.

Her other idea was to insist that children had at least some role in the writing of each song. So much of the storytelling at Junior Eurovision is, naturally, written from the children’s perspective, and Zoë Jay has some concerns about that power dynamic.

“So they [the artists] have got a lot of power in terms of at Eurovision in terms of being the faces of these sort of messages. But they don’t necessarily have a lot of power in terms of choosing those messages.”

My reaction to reading Zoë’s work and interviewing her is that we adults should be increasingly delicate with how we cover and talk about Junior Eurovision. Are we imposing our values on the competition, or are we listening to the true words of the next generation?

In terms of unicf, if I remember correctly. They have been tied in with junior on at least 3 separate occasions.

With the last part about the writing. While it is a delicate balancing act, have the kids at least have an influence or a say on the writing side. Even if songwriting is not their strongest suit, let them have a say in the process. Without adults welding unreasonable power in the relationship.

The strangest thing about JESC for me is how the results are very often adults voting for what they think children’s songs *should* be like – as a teacher of young children, I can confirm that none of them would ever listen to anything like Oh Maman or other songs that have done well recently out of choice.