Liverpool’s Magical European Nights

When the world gathers around TVs, crowds into public squares for open-air screens, and packs into the Liverpool Arena on May 13th 2023, it’s going to feel special. The eyes of the world are going to be on Liverpool as it carries the mantle of hosting the Eurovision Song Contest. If you wanted to sound clichéd, it’s going to be one of those ‘magical European nights’ that we as Eurovision fans look forward to every year.

This will not however be the first time that this city on the Mersey plays host to a magical European night. In fact, if you type those three words into Google, you’ll find the majority of the entries relate to the magic of football and specifically to the city’s most successful team, Liverpool FC. The term was coined from the fact that Liverpool has a consistent record of achieving extraordinary things at their home stadium Anfield in European competitions; from overturning a three-goal deficit against Barcelona in 2018, to winning 4-3 from 2-0 down against Borussia Dortmund in 2016, and even winning a Semi Final against Chelsea in 2005 with a ‘ghost goal’.

Liverpool fans will point to a number of different reasons for the team coming alive in Europe. Some point to the team’s record as the most successful English club in European competition, others will point to the innate belief that if strange magic has benefitted the team in the past, and that belief that it could happen again galvanises the players.

I would attribute it to a tradition which started at this particular club but has since been copied by clubs the world over who have followed Liverpool’s lead. Once all the players from both teams are on the pitch at Anfield, the stadium PA plays ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’ over the speakers and the home support raises their team’s scarves in the air and sings along. Although on paper, there is something utterly surreal about 50,000 Merseysiders singing a Rogers and Hammerstein song from 1945, the end result is electric amid an atmosphere that not only defines the football team but the wider city as a whole. This article will explore how an American musical number became one of the defining symbols of this year’s Eurovision host city.

It started with a Carousel

‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’ is a song from the musical Carousel. It’s performed in the second act of the show by the protagonist’s cousin after the protagonist’s husband dies in her arms from a self-inflicted wound. It’s then reprised at the end as the deceased husband returns to earth to watch his (and the protagonist’s) daughter as she graduates.

For many years, the song’s cultural significance was limited to performances of Carousel with little fuss made about it beyond theatres. In 1956 however, the musical was turned into a film and it was at one of the film’s screenings that a young Liverpudlian named Gerry Marsden (who’d come to the cinema to see Laurel and Hardy before falling asleep) became captivated by that particular song, becoming one of his instant favourites. Marsden brought the song to his band, Gerry and the Pacemakers, who were unconvinced about recording a cover of a showtune but whose opinions changed after they heard how their cover turned out.

Their version of ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’ would peak at number 1 in the UK singles chart becoming the band’s third consecutive number 1 hit – incidentally making the group the first act in UK chart history to do so with their first three singles. The song would remain there for four weeks whilst also reaching the chart summit in Ireland, Australia and New Zealand.

Meanwhile in a Stadium Not Far Away…

Liverpool FC (as they are today) were one of the city’s football teams and a cultural institution on Merseyside. However at the time of Gerry & The Pacemakers’ success with ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’, they weren’t even the most successful team in North Liverpool. Everton (who play on the opposite side of the city at Stanley Park) had wrapped up their sixth league title (surpassing Liverpool’s five at the time) and had won two FA Cups (in comparison to Liverpool’s zero). In fact, it was only the previous season that Liverpool was playing an entire division lower than their city rivals. In Bill Shankley however, Liverpool had a no-nonsense manager who was determined to use the grit and determination that he developed from his Scottish mining heritage and instill it in his team.

Meanwhile on the terraces of Anfield, things were getting musical. The stadium announcer was making a regular habit of playing the top 10 songs in the UK singles chart in descending order at every home game. Fans on the Kop (the single-tiered West stand) enjoyed singing along to all the hits of the day but somehow ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’ encouraged more people to sing than usual.

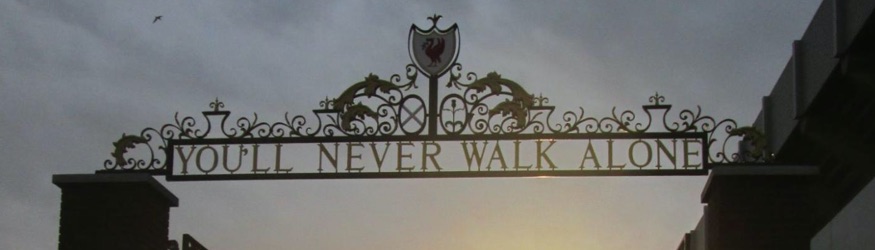

Perhaps it was the home fans’ pride in a local band scaling the charts? Perhaps it was seen as representative as the perfect message for a group of fans to send to their team pre-match? Perhaps it’s just a song that was really easy to sing along with as a result of its slow beat and easy lyrics. Whatever the reason, once the song dropped out of the top 10 and the Anfield DJ stopped playing the song, the crowd immediately began shouting at him to return it to his pre-match playlist and it has been played at Liverpool’s home stadium before every match they have played there ever since. In 1982, the words ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’ were designed into one of the stadium’s new gates commemorating Bill Shankley’s legendary tenure as Liverpool manager.

Anfield Gates (Photo: Fin Ross Russell)

A Tragedy in Sheffield

Coincidentally or not, Liverpool’s stratospheric rise into the pantheon of football history was almost immediate from that 1963-64 season when the song became such a hit amongst Liverpool fans. The team won their first league title since 1947 that very season and would go on to win it eleven further times in the subsequent twenty-four years. In that same period, they would win the European Cup four times. Liverpool became a force to be reckoned with both internationally and domestically. They would also win the FA Cup three times, rubber-stamping their dominance of their English opponents in one of the world’s oldest cup competitions. It was this competition that Liverpool fans were about to develop a special connection with when it was linked to the most deadly disasters in British sporting history.

In 1989, Liverpool and Nottingham Forest were drawn against each other in the Semi Final of the FA Cup. As is tradition, the Semi Final of this competition is played at a neutral venue and the Football Association selected Sheffield Wednesday’s Hillsborough Stadium to host the match.

Liverpool was allocated the North and West stands of the stadium but because the main turnstiles to enter the stadium to the East were cordoned off in order to segregate the two sets of supporters, all Liverpool fans were forced to congregate at the narrow Leppings Lane entrance to the stadium to the West of the ground. English football in the late 1980s had been marked by several incidents of hooliganism with Liverpool having been involved in the 1985 Heysel Stadium Disaster which led to the deaths of 39 people and English clubs being banned indefinitely from playing in European competitions. The newly promoted South Yorkshire Police Chief Superintendent David Duckenfeld was focused more on the issue of hooliganism than the dangerous build-up of people that was developing right before his eyes despite the numerous incidents of fans being packed in too tightly which had taken place in this very stand previously and the fact that the West stand that they were packing into did not hold a valid safety certificate.

With no experience in commanding a sell-out football match and very little training, David Duckenfeld thought hard about what he should do to relieve the pressure. His solution was to instruct the police to open Gate C, an exit gate usually opened to ensure fans safely leave the stadium post-match. Now the 5,000 fans who had built up outside the turnstiles began rushing towards the terraces and many of them towards a narrow tunnel that led into the stand’s central pens.

As a result of the aforementioned hooliganism issue, stands in the 1980s were segregated in order to control the flow of people into them and prevent overcrowding. They were also segregated from the pitch by a large metal fence meaning they had a limited number of places to escape to in the event of an emergency. People were packed tightly against both each other and the pen fences and police (who would normally stand at the entrance to the tunnel) failed to direct people to the side pens once the main pen had reached capacity. The match was stopped after five minutes of play but by that point, it was too late. 97 people died in the crush, mostly from compressive asphyxia with victims as young as 10 and as old as 67.

Several people who witnessed the events would go on to take their own lives as a result of the trauma they experienced at Hillsborough.

For the families of the victims however, the closure they sought from their grieving processes couldn’t be further away. South Yorkshire Police had already begun feeding false stories to the press about the disaster, claiming that the main cause had been the drunkenness and hooliganism of Liverpool fans that had caused the crush. Even though the 1990 Taylor Report laid the blame at the feet of South Yorkshire Police for their poor crowd control, the 1991 coroner inquests would still rule the deaths as accidental. In 2009, the British Government set up the Hillsborough Independent Panel to re-investigate all the materials surrounding the disaster. In 2012, the panel revealed its findings which absolved all Liverpool fans of all blame and reinforced the findings of the Taylor Report regarding the role of the police. The panel’s report also went on to find evidence of a police cover-up and the gut-wrenching news that had emergency services response been coordinated better, that 41 victims could have survived. The report led to a second coroner inquest which in 2016 concluded that the deaths had resulted from unlawful killing.

Despite being charged with 95 counts of manslaughter by gross negligence, Duckenfeld was found not guilty of all of them in May 2019. To this day, nobody at South Yorkshire police has been found guilty for their role in the Hillsborough tragedy.

In the days that followed the tragedy, ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’ was a song that reflected both the shock and sadness but also united and determined feelings of a bereaving city. This was reflected in the song’s inclusion as part of the Hillsborough Memorial service at Liverpool Cathedral the day after the terrible events in Sheffield.

Liverpool would go on to win the re-arranged semi final match against Nottingham Forest to set up a final with city rivals Everton. Despite the rivalry between the teams, fans of both sides sang along to Gerry Marsden’s performance of the song pre-game before watching their teams play out one of the greatest FA Cup finals in history which Liverpool went on to win 3-2 after extra time. The song’s lyrics of hope, resilience and togetherness in difficult times brought together a fanbase in their greatest time of need. It’s, therefore, no surprise that on many of the subsequently made memorials to the tragedy (including the one at Hillsborough Stadium today), you will often see ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’ etched in. It is without a doubt that the song’s significance in this period contributed to the title being included on the club’s crest from 1993 where it has remained ever since alongside two flames on either side in memory of the victims of Hillsborough.

Hillsborough Memorial, Sheffield Wednesday. The Memorial has since been updated to remember Andrew Devine, the 97th victim, who died in July 2021. (Photo: Fin Ross Russell)

A Worldwide Legacy

From its unique beginnings on the Anfield Terrace, ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’ has become a football anthem sung across the world with different clubs having their own incredible stories linking them to the song via Merseyside.

On Liverpool’s run to the 1966 European Cup Winners’ Cup Final (not long after Liverpool had adopted ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’ as their club anthem), they played Celtic in the Semi Final and Borussia Dortmund in the Final. Both clubs now play the song before home games although Dortmund’s connection was focused around local band Pur Harmony deciding to cover the song in 1996. Some of the greatest videos online of ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’ being sung at football stadiums are when these teams have met and the whole stadia have united in song.

When Enschede-based FC Twente played their last match at the old Diekman Stadium, Anfield stadium announcer George Sephton “gifted” the song to the team. They now play the song before every home match at their new stadium. Other teams known to have sung the song before home games include Feyenoord, SC Cambuur, Mainz 05, 1860 Munich, Admira Wacker, Club Brugge, KV Mechelen, FC Tokyo, CD Lugo and ARIS. It’s also known to be sung by ice hockey teams Krefeld Pinguine and Medvescak Zagreb.

Every Other Saturday Afternoon

When I’m not following the Eurovision Song Contest, I am often found travelling across the United Kingdom enjoying football of differing quality at various stadiums in incredible parts of the country. On December 11th 2016, I made my first journey up to Merseyside to watch my team West Ham United face off against Liverpool.

Even though I’m not a Liverpool fan, the stories around the club, its history and its culture are footballing mythology and I was keen to experience what being at Anfield to soak it all in would feel like. The experience was very special from the moment I stepped off of the bus and walked around the stadium to see panels reflecting on special matches at the historic stadium and pictures of club legends.

I passed behind the iconic Kop stand and thought of all the videos I’d seen from the ‘60s of Liverpool fans singing popular songs of the day pre-match on those very terraces. I passed underneath the Shankley Gates with the words ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’ greeting you as you enter this hallowed ground. I passed underneath the Paisley Gates with symbols of their legendary European Cup victories etched in.

I stopped at the Hillsborough memorial with the names of all 96 victims and their ages (the 97th would pass away in 2021 from injuries sustained at the match) alongside flowers, shirts and scarves from teams across the footballing world focused around an eternal flame. I made sure I entered the stadium early both to soak in the atmosphere and ensure I was there when the home fans raised their scarves and sang their famous anthem.

After the teams came out, the sounds of Gerry & The Pacemakers began to play and the rest was spell-binding as decades of a city’s culture, history and character mixed together in this stadium as a cry of unity and togetherness for their beloved team.

Anfield Memorial for the 97 (Photo: Fin Ross Russell)

We will hear many songs during our May sojourn in Liverpool but few will have quite the special meaning to locals as ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’, a song created as a show tune that became a symbol.