Let’s take some time to imagine. Imagine that we are living in a Eurovision competing nation ready to watch the Grand Final. Our nation competed in the Eurovision Semi Finals as is tradition, and we were proud of the song our nation sent. However we couldn’t vote for our entry, and it turned out that not enough people in Europe did either.

We don’t have any patriotic pride on show for the Saturday night.

Except yes we certainly do! After all the songs have been performed and the recaps have rolled around now comes the most important part of the show, the voting. Every nation that competes in the Eurovision Song Contest, even those that got eliminated during the Semi Finals, gets their 30 seconds of fame during the voting sequence. Our broadcaster has assembled five of our most knowledgeable musical experts to watch the performances and vote for what they thought were the best Eurovision songs.

There aren’t many occasions when spokespeople from around 40 different nations are able to broadcast to each other live. Even the simple thing of seeing our national monument as the backdrop on screen and knowing it is being shown across the whole of Europe is a big deal. Hearing the points of our jury is a source of great pride.

For six of the competing nations in Eurovision this year it didn’t work like this. The juries from Romania, Poland, San Marino, Georgia, Azerbaijan and Montenegro were disqualified from revealing their votes in a statement released just prior to the votes being read out. Instead, those revealed results were produced from the results of juries made up outside of the nation. Sure the broadcast may have presented them as the Romanian votes, Polish votes and so on, but their source came from outside the country.

The moment of national pride for these countries was lost. As discussed in our previous article, the alternative points provided were not necessarily a good alternative, either for the broadcasters presenting their points or for mathematically replicating what those juries should have awarded as their final ranking.

So what would be a good solution?

The Scientific Method

Let us put on a scientist’s hat here, and consider what one does in an experiment here with a result that one knows has been recorded incorrectly. Such a result is deemed to be an anomaly. What do we do when an anomalous result is discovered? Before I tell you, why don’t you have a go at this multiple-choice quiz about what is the correct scientific approach to make?

The answer to Question 5, asking about what to do with anomalous data, is as follows:

“Bad data is still data. If there are anomalous results, the best thing that you can do is to repeat the experiment. When that isn’t possible, discard them but always state why you did that in the evaluation section”

If we apply this idea to the Eurovision Song Contest voting we hit an immediate problem. Repeating the experiment is not possible, we don’t have the time to organise a new jury to do a repeat vote, and there are no backup juries that exist to the main jury in each nation. Should a result need to be discarded therefore the accepted scientific practice is to discard the results, but make sure you explain why you are discarding them in the process.

That was not the case in Turin. The result presented was a smudge, attempting to fit other data to replace a point by trying to fit into the other known patterns. From a strictly scientific viewpoint, this is poor practice, as it increases the risk that the result given is false. Given what we know about the small sample size of juries and their high variance to each other, the chance is that we will not replicate a jury vote to a desirable level of accuracy.

The question is, can we create a system that would treat disqualified juries in the same way that scientists treat anomalous data?

Removing The Data

Here is a proposal that stays true to the scientific method. If the EBU believes that a jury has not voted in accordance with the standards they expect, that jury should be disqualified. If a jury is disqualified, the following steps should happen.

- The points that the jury gave out should be removed. That nation effectively gives out a zero to each nation taking part.

- During the live broadcast, that jury will not be called to give any points out and are skipped over in the presentation.

- The act representing the broadcaster that saw their jury disqualified will start the voting sequence with a 12-point deduction as a penalty.

As per the scientific method, if we have to delete data we need to explain that in our report. Applying the same here, we need to explain to the viewers that we have removed juries from our ranking. In this proposal, this means the viewers would need to be aware of this happening during the live broadcast. That announcement would need to say not only why we are not going to those nations to receive their votes, but also explain the 12-point deduction that the artists from those nations have.

The 12-point deduction is a sad yet necessary tool in this scenario when the data is discarded. If one country did not vote, but all the others do, then that is one extra country that the artist in question can receive points. Starting on minus 12 will negate that being an issue, as it is the equivalent of if the jury was allowed giving out 12 points to every other nation, meaning no advantage is gained.

How This Would Look In Practice

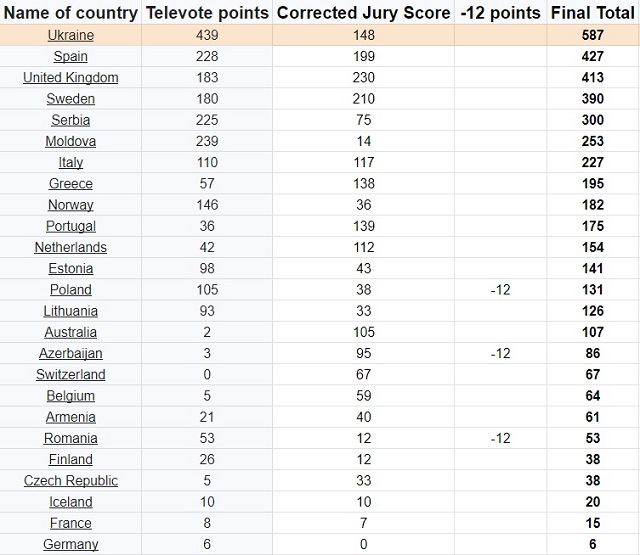

I have modelled the 2022 Eurovision Second Semi Final and Grand Final using this method, and the results would have altered ever so slightly.

The big change here sees one difference in the qualifiers that would have reached the Grand Final. Azerbaijan only scored points from the juries and with six jury scores removed (that all included votes to Azerbaijan in their calculation) that is enough for them to fall back to 77 points from juries. This, combined with the -12 point penalty means Azerbaijan tied on points with North Macedonia in this simulation. North Macedonia would have squeaked the last qualifying place by virtue of having more televote points.

The other slight differences come mainly from the fact that the vote is no longer a 50/50 vote (with six juries removed there are now 21 televotes – including San Marino’s calculated televote – and 15 juries, so the split is 58/42). Australia is a good example of this affecting the outcome, which finished 2nd in the actual Semi Final due to a very high jury score, is now pulled down to 4th behind Czech Republic and Serbia. Note that Australia had received 6 sets of ten points from the replaced juries from the six disqualified nations.

Now onto the Grand Final.

For the Grand Final, we still see a comfortable victory for Ukraine based upon the humongous televote score that ‘Stefania’ received. However, they are followed by Spain which edges out the United Kingdom in this alternative universe. ‘Space Man’ did receive 53 points from the six juries that had their scores replaced by the EBU, an average of 8.8 points per nation. The average the United Kingdom received from all the other 33 nations that could vote for it was lower at 7.0 points per nation. On the flip side ‘SloMo’ struggled with the disqualified juries, receiving on average 5.3 points from those six nations, compared to the average of 6.0 that ‘SloMo’ received from the other 33.

Overall there are no great movements in the table, with no country moving more than a couple of places. Note too that the impact of the -12 point negative drag is reduced in the Grand Final as the number of competing countries that take part is increased (with 40 televotes and 34 juries the televote/jury split is 54/46).

Science Or Art

The major benefit of removing the corrupted dataset from our Eurovision scoring is that it is the cleanest solution to deal with an issue such as an unprofessional jury. No data needs to be calculated to represent a broadcaster that comes from another broadcaster, and all the points awarded are from ‘real’ data.

However, this will come with risks and more than just making the televote/jury vote lopsided. Making such a decision this year would have dramatically changed the broadcast, cutting around three minutes from the four-hour extravaganza at short notice. It would most certainly need to be announced prior to the show as well, as these countries would not be presenting their votes on the live broadcast in any way, shape or form. The scandal that would create would be impossible to hide and would face levels of fury easily surpassing those shared about this year’s events. A question mark would also need to apply for cases where a jury vote can not be given for a reason not based on perceived cheating, such as a technical problem. Who would want to punish the artist on the ground for something that is nobody’s fault at all? In this case a 12 point penalty is no good solution. This tool would only be one that could be used for punishment.

Yet even so deducting points is delicate to the Contest, as even if the broadcaster suffers it also affects an artist who should be immune from such drama. While a 12 point penalty is a tiny fraction of the total points, it could make the difference between qualifying or winning. Is it right to punish the artists for errors made by those who’ve likely never interacted with them?

This is where it is difficult to establish what the Eurovision Song Contest is on the scale of pure sport or pure entertainment. In sport it is commonplace to punish the team on the scoreboard for events off the pitch, with a 12 point penalty awarded to teams in England that fall into financial administration a common example. Sport has determined it is acceptable to punish individuals in the team for malpractice run by the team’s organisation.

But is applying a sporting solution to the world of arts just? The current situation is one that leans on the side of Eurovision as entertainment rather than Eurovision as a sport, by hiding corrupt jury voting from the public eye as far as possible. The solution we propose pushes the Song Contest further towards sport, competition and emphasis on the scoreboard above all. Is that the culture we wish the Song Contest to be?

I leave that question unanswered. It is for the community to help decide where on the sporting competition/entertainment show spectrum Eurovision should end up.

A Solution Is Needed

Regardless of what solution we ultimately end up with, I hope we all agree that the disqualifications from this year’s Song Contest should trigger change to the system. Member broadcasters of the EBU should not need to find out late during the live broadcast, which left some spokespeople unable to participate in the continent’s biggest Saturday night show after going through all the preparations and rehearsals that day. The methodology for replacing a disqualified jury score needs to be opened up; it shouldn’t be something for the community to have to reverse engineer but an open and transparent way for us all to calculate the outcome. Furthermore, the actual calculations themselves need to be evaluated – for simulating jury results the procedure is too far from producing an accurate copy of the disqualified jury to be passed off as an acceptable replacement for the fairness of competition.

One hopes that the Eurovision Song Contest will never see a situation where thirty music industry experts will have their votes removed again. Yet it may, and we need a system that can better cope with such an event and more robustly keep the integrity of the Song Contest as high as possible.

commendably informative!

Fantastic article. Really enjoy your insights Ben. Thank you