Nobody in the Eurovision Song Contest world can come anywhere close to being as creative as the Swedes.

On the Eurovision stage Sweden in the last five years has always reached the top ten at the Song Contest no matter what genre it sends, winning awards for staging as well as music. The two Eurovision editions Sweden has recently hosted in 2013 and 2016 have not only been some of the most quality productions on and off screen but also the cheapest to produce.They also have a National Final system in Melodifestivalen that is not only the most watched TV show in the country but also the competition many other Eurovision nations would aspire towards.

The voting system of Melodifestivalen had a major overhauled in 2011, after Anna Bergendahl did not qualify to the Eurovision final. Since then half of the results in the final were from international juries and half from televoters. While jury/televote splits are nothing new, bringing in jurors from other countries has infected selections for Finland, France, Romania and beyond. Many broadcasters are looking at Sweden and seeing this as one change they can do to improve their Eurovision results in May.

Bilal Hassani won both the international jury and televote in France’s Destination Eurovision Semi Final

One more recent change that hasn’t been picked up by other countries has been with Melodifestivalen’s voting app. Launched in 2015 Melodifestivalen’s smapp records votes through button-bashing the screen to vote instead of traditional text or phone methods.

The benefits of the app are many. It bypasses the phone networks so means app voting is free, increasing the sense of democracy. It also can be far more intuitive than having to text or call a certain number and means that votes can be cast far quicker than before. Other features such as predicting the results and seeing how your friends voted increase engagement with the show. That engagement is massive, with Melodifestivalen’s project leader Anette Helenius claiming 1 in 5 viewers are using the app to vote.

That said, the app has many critics. Some argue that an app based system has overly trended towards young people’s taste, with a savvy smartphone generation able to vote far stronger than older viewers still calling in. Others use the ‘heart-symbol’, which shines on screen more when more votes are cast, to decipher with scary accuracy how successful songs are even before recaps have been shown. The app also has been one contributing factor to Melodifestivalen’s rather pedestrian voting sequence in the final show, where so many millions of votes are cast that the televote score has the standard deviation as tiny as San Marino’s qualification record.

More app votes resulted in a stronger heart symbol on screen during the previous editions of Melodifestivalen

While the app has been refined each year slightly, this year is undoubtedly the biggest change to voting since its introduction in 2015. What is remarkable is that this change has only been possible because of one enormous advantage apps have to other voting methods. You have to consent to send in your data. With four years of data at their disposal SVT have made grandiose changes to their voting system which I believe every other broadcaster, and even the EBU, will be watching with great interest.

Update In Progress

The headline news is that SVT are now dividing up voters into seven different categories based on the age you use to sign up for the app. Those age categories are as follows:

- 3 to 9 year olds

- 10 to 15 year olds

- 16 to 29 year olds

- 30 to 44 year olds

- 45 to 59 year olds

- 60 to 74 year olds

- 75 years and over

Anette Helenius explained that the rationale for chosing these age bands was to group viewers who had similar ‘lifestyle’. Although there are slight variations to the scoring system as you go through the Heats, Andra Chansen, and the Melodifestivalen Grand Final, the basic system remains the same. When you log into the app, you have to give your age. You then vote in the voting block of people the same age as you. Each block has an equal sum of points to give to the songs. The votes of people aged 75 and over will create a voting block of equal value to those aged 30 to 44, for a total of seven blocks.

The televote, for the heats and for the final, will be used as an eighth block of equal voting size to the seven from the televote. The opportunity to text vote will disappear completely. In the Grand Final an international jury of eight countries will remain, and give out points equal to that of the seven different app groups plus the televoters for a 50/50 points split.

Dividing up jurors by voting age isn’t anything new in the Eurovision world, but I have to go back to the days well before my birth to find those systems.

Eurovision 1973: One juror 25 and under and one juror over 25 from each country.

This is revolutionary by SVT and I strongly believe will make a stronger voting system for the competition.

Why These Changes Will Bring Success

As mentioned above, one of Melodifestivalen’s biggest criticisms has been that the songs that do well all belong to genres of pop music that appeal to younger viewers. The 2016 final is a good example of this where the oldest artists were only in their thirties and were performing songs aimed at far younger audiences.

While Anette Helenius says that ‘it has been clear that songs that perform well do well with all age groups’ they have ‘listened to viewers’ and made this change. As all Eurovision fans would know well, to win the competition you have to get points from the vast majority of competing countries. It would be little surprise to suggest as Anette does that songs doing well in Melodifestivalen get points from all voting ages.

Nevertheless the dominance of youth-friendly tracks has been high, arguably too high, in the race to qualify to the final. With the ‘middle’ voting group aged from 30 to 44 years old this change may be the little tweak needed to increase the diversity of songs that reach the show in Friends Arena. Gustav Dahlander from SVT’s Melodifestivalen team has said that the 2018 qualifiers to the final though would not have been different with this system. Perhaps it is more of a cosmetic change.

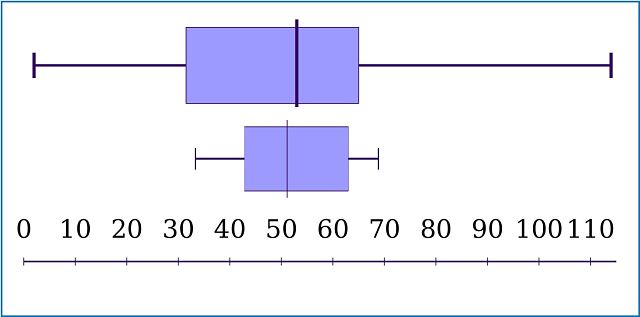

However a more substantial change is the much needed improvement to the voting system of that Friends Arena Final. Last year the spread of votes in the Melodifestivalen final was very small ranging from 37 to 67 points – far less than the juries spread from 2 to 114.

The spread of international jury scores (top plot) compared to app votes (bottom plot) in the 2018 Melodifestivalen final

The Melodifestivalen final of last year was officially a 50/50 jury/televote split, however in practice the ratio was much more weighted towards the jury. The new system will still be 50/50, but each voting block will vote in the same style as the jury – with 12 points to their favourite. I would actually predict here, if Anette is correct and voters of all ages agree on which songs are best, that actually 2019 gives more advantage to the voters at home over the jury. It will be fascinating to see.

A small but subtle change will also come in the presentation of the app during the show itself. The heart symbol remains, but no longer will it glow based on how popular a performance is. Instead the symbol will glow different colours (a maximum of three) based on how much the song has been voted on by different groups. Expect to see more greens and blues (the youthful colours) for Dolly Style and more oranges and reds (the older colours) for Arja Saijonmaa. Because each voting block, and therefore each colour, has equal value, gone is the concept of predicting a winner before the song has even finished performing. This is ultimately a huge improvement to the viewer experience.

One Step Too Far?

Although this voting system has so many benefits, it also shows a speed of modernisation that even Sweden may struggle to keep up with. The dropping of SMS voting is one, but also note that for Andra Chansen televotes will not be possible in the presumably small voting window. The app is quite clearly the future, but is the nation ready for it just a few years into the change? It’s one thing in Stockholm to walk around hipster markets paying for everything with your mobile phone, but is that the same reality as for every Swede from Luleå to Lund?

Furthermore, the selection of the voting blocks is bizarre, and defined seemingly by SVT’s arbitrary lifestyle groupings. While I can imagine many Swedish three-year-olds have the capability of voting on the easy-to-use app, a question mark has to come about the ability to vote coherently from a three-year-old. Should a three-year-old vote be given equal value? Of course downloading an app, inputting their age correctly and consenting to allowing SVT to use their data will have to be done by their parents/guardians. It’s one thing borrowing mummy’s phone to vote, it’s a different thing to have that responsibility yourself. The children’s age category will likely come under heavy scrutiny once results are revealed.

Gustav Dahlander also reveals big albeit unsurprising differences with the app itself, revealing that viewers aged 15 are six times more likely to vote than those aged just 50. Even though the age range from 45 to 59 age range is larger than that from 10 to 15, extrapolating this data would suggest the 10 to 15 year old voting block to have a larger voting population.

Samir and Viktor qualified three times to the Melodifestivalen final

Think about this another way. If you are watching the Eurovision Song Contest from Latvia or from across the border in Russia, which country gives you personally the biggest individual voice? Latvia of course as their population is smaller. Will it be possible in the new system to register a different age for yourself so your vote is worth more than your peers?

Another thought is also that just because you have logged in with a certain age, doesn’t mean that the same person will be the one voting. Is one reason the votes are almost always the same with different year groups because younger children are using the phones of parents to vote themselves? This is where SVT’s big data approach may fall down. It would also explain some bizarre voting on the app that I have witnessed (one can see how friends have voted) in for example voting for both songs in an Andra Chansen duel. Perhaps there isn’t just one person behind the vote. Perhaps this process is too perfect to work in practice.

However, voting in Melodifestivalen isn’t just about record results, it’s about getting everybody involved in the good mood party, and this should be a huge win for the app.

A Party For All Of Sweden

It’s highly symbolic that the colours of the rainbom span through the new voting blocks in Melodifestivalen. Every colour is in the rainbow. Every type of song should be in the competition. And every person in Sweden should be tuning in and getting their voice heard.

After all, they call Melodifestivalen here ‘Hela Sveriges Fest’ (A Party for All of Sweden).

The current mood locally in Sweden is that the show has become less of that in recent years. And it is a big deal to make it a party for everybody. Look back on how the songs are selected in the Melodifestivalen jury room – all divided up by genre, by language and by the gender of the composers. There should be role models from all walks of society on that stage, performing to all the viewers at home. It is a clear part of the public broadcasting service that SVT tie up with running Melodifestivalen.

The impression currently dominating Swedish society is that Melodifestivalen is a young person’s game, and you have to appeal to the youth of today to get ahead. If that perception lingers then Melodifestivalen’s diversity will be lost. This change is a step in the right direction to increase the interest and voice from all people in Swedish society.

Everybody can be a part of this, and everybody should have an equal say in the outcome.