Why is there such a discrepancy in the televote and the jury vote? It’s a question asked by many after each edition of the Eurovision Song Contests (and also asked after many National Finals). Following another Eurovision first that happened in Lisbon we can add another piece of evidence to this question.

It’s also a fun opportunity to strip back the Song Contest, remove one of the senses that contributes to the experience, and take a different look at the Contest.

Eurovision Song Contest Trophy 2018 (Thomas Hanses/EBU)

“Doesn’t He Look Tired?”

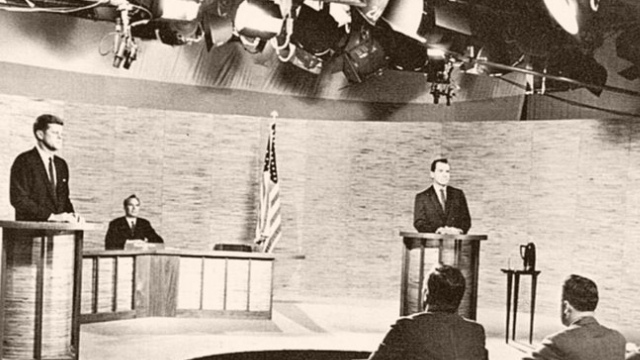

But first, let’s turn briefly to one of the most notable and competitive events where TV and Radio offered different angles – the 1960 US Presidential debate between Richard Nixon and John F Kennedy.

The more experienced debater in Nixon (at that time the sitting Vice President) took on the issues of the day and strongly argued many points – mostly on foreign policy in the first debate – that many called the debate a victory for Nixon. At least those who were listening on the radio.

Sen.John F.Kennedy (l) and Vice President Richard M.Nixon from NBC studios 10/7

Thanks to his experience of political debate on radio, Nixon understood the format, knew how to measure his voice, understood how cadence and pitch could be used to make subtle points, and why he needed to be less of an attack-dog to soften his image. What he didn’t consider was how well his suit jacket blended into the background of the set, how his failure to ask for TV makeup emphases a ‘five o’clock shadow’, and the impact of his slumped physical shape.

The victory on TV, and arguably the overall victory, went to Kennedy.

Even today, when test groups are gathered to measure the difference between the TV and the Radio presentation, Nixon takes the radio while Kennedy takes the television (The Power of Television Images: The First Kennedy-Nixon Debate Revisited; James N. Druckman; The Journal of Politics; Vol. 65, No. 2 (May., 2003), pp. 559-571):

I find that television images have significant effects—they affect overall debate evaluations, prime people to rely more on personality perceptions in their evaluations, and enhance what people learn. Television images matter in politics, and may have indeed played an important role in the first Kennedy-Nixon debate.

The Euroradio Song Contest

Even though we all know what is meant when the public says ‘Eurovision’, strictly speaking Eurovision is just the transmission network that connects the member broadcasters of the EBU. This isn’t the only network maintained by the EBU, there is also Euroradio. The EBU’s members not only had the option to broadcast the Eurovision Song Contest on television, they also had the option to broadcast the Song Contest on radio (although it would still be called the Eurovision Song Contest, not the more technically accurate Euroradio Song Contest).

That also means that the rights for radio broadcast are available to passive broadcasters – an option that was taken up in the US this year by Dave Cargill (Executive Producer at Cargill Gardiner). Along with the support of the EBU, Portuguese broadcaster RTP, lead US station WJFD, and the legendary production team of Radio Six International’s Tony Currie and Leo Currie; Ewan Spence, Lisa-Jayne Lewis, and Ana Filipa Rosa took to the American airwaves with the first US radio broadcast of the Eurovision Song Contest.

You never want a blank monitor during a broadcast (image: Ewan Spence)

Which meant that this year there was an interesting option to have a group of professionals in the music and radio business the chance to sit down and listen to the Song Contest without the visuals from the Altice Arena, but with a professional commentary team guiding them through the process. Naturally we took notes…

What The Panel Thought

Like many of those listening in America, the radio panel (which may be the closest we get to an ‘American Jury’ at the Eurovision Song Contest for many years) had not been following the Song Contest in excruciating depth – they covered people who knew and listened to the Song Contest because it reminded them of their family’s home, those who were aware of the Contest in a broad sense, and some who were new to the entire concept of the Contest. In other words a relatively representative slice of the population.

Of the twenty-six songs in the Grand Final, there was a clear winner from the panel, with all bar one of the top spots going to Austria. Perhaps unsurprisingly the audio performance from the Netherlands all scored highly and was the only other country to top a panellist’s list, and was second with those who rated Austria first.

Three other songs had very strong reactions – the Czech Republic, Lithuania, and Germany. At the other end, Hungary, Serbia, and Australia picked up the ‘nul points’ from our panel.

The feedback also had some delightful questions, with my favourites including ‘When does Armenia come on’, requiring a quick nod to the semi-finals and reminding our Armenian panelist that Sevak did not qualify; and ‘what does the crowd do when waiting for the next song?’ Which is a good question…

Implications

This year thirteen EBU members broadcast the Song Contest on their radio networks, but there is no clear way to break out the votes in each country to those watching on TV, those watching on radio, and arguably those watching online through other methods such as the EBU’s YouTube channel or those preferring to watch another broadcaster (e.g. expat Swedes watching the SVT stream). Every country has one main number for the public to call in and vote on.

In terms of Eurovision winning strategies, there’s not a large enough audience tuning into the radio that would merit a specific strategy – the mix of visuals with the singing remains key to the televote – but it’s worth noting that the songs that performed well to the radio listeners also scored highly in the jury voting during the Grand Final. While juries see the EBU TV feed and can see the full package, the US panel only had the audio to judge. There is a clear trend towards the juries following a similar pattern and focusing on the singing.

At one point, each jury member voted live on screen (EBU)

When the split results come in each year, there are always questions about why certain songs have such a wide discrepancy between jury and televote scores. Part of that could be down to the difference between Friday night and Saturday night, but Eurovision’s radio presentation in the USA suggests something more fundamental.

The professional juries are putting a greater focus on what is heard over what is seen.

Do Try This At Home

Due to rights issues, Eurovision’s US radio broadcast is not available online to ‘listen again’. EBU members who broadcast the show on radio may have it available on catch-up services.

Or you could head over to the official Eurovision channel on YouTube, pick a year (here’s 2016), and minimise the window just after you hit play. Maybe go back a few years so you can’t remember the exact results, score the songs, and see if you are closer to the televote or the jury vote.

Interesting article there – I have been a guest on a local community radio show for four years now and we have done something very similar. We listen to all the official studio entries in the run up to the Contest and judge them solely on the vocals, nothing else – it is always more difficult for me, having a good idea what they have sounded like live and seen how they perform. The last two years we have matched up with Salvador and Cesár, much in the same way as the juries and your experience above.

It was also interesting that when we had 20 somethings listening that they matched quite closely with radio friendly entries such as Poli, Kristian and JOWST – maybe an argument for as wide a range of demographics in the jury set-up as possible? Those first impressions these jurors get are now lost for most of us obsessives – when is the first time we hear most of these entries now? Months before they get sung at the Contest…