The Eurovision Song Contest interval act is an opportunity for the host broadcaster to show off their nation’s cultural capital however they see fit. Sweden’s current global pop supremacy makes them power players in the interval act game. Could bringing Justin Timberlake to the Song Contest , in the first year that the US are ‘officially’ watching the show, help Sweden demonstrate enough pop cultural capital to equal Ireland’s all-time Eurovision crown?

Over the decades, host broadcasters have drawn influences from all kinds of high and low culture to provide the half-time entertainment, with varying levels of success. You can draw all kinds of messages about what was considered to be TV-worthy light entertainment throughout the second half of the 20th century through looking at Eurovision Song Contest interval acts, and, of course, witness the birth of a bona fide global phenomenon. Looking back through the archives, I found that you can put the interval acts into rough chronological groupings and that within those groupings you can make inferences about the influences of the people who put these shows together. Gather up your children’s choirs, mimes, stilt walkers and fire-eaters; it’s time to talk about the interval acts.

1956 to 1966 – Straight From Variety

In the era where the format of the show was in flux, there wasn’t always an interval act, so it’s hard to draw conclusions as to the main inspirations. However, the early Contest had a similar format to the light entertainment variety shows which were extremely popular on both the TV and the radio at the time. In this period, we’ve got a novelty whistling act, a physical comedy act with a bicycle, some nice smooth dance bands and a rare genuinely amusing clown in the form of Achille Zavatta. In 1966 the interval was covered by jazz band ‘Les Rouges Haricots’, who had a slight whiff of beat combo danger about them, which sat nicely alongside the hints of mod and Merseybeat in the competition songs that year. Something new and exciting seemed to be about to impinge upon the Contest. Whatever next?

1967 to 1975 – Let’s Do Something A Bit Different!

While people put the start of the Swinging Sixties at about 1964, the first hints of the counter-culture didn’t reach the Eurovision Interval Act until about 1967. In the wider fields of music and the performing arts outside Eurovision, these were exciting and creatively fertile years. Many of the interval acts reflect this rush of creativity by including new, uncomfortable and challenging elements of high art within the light variety show format. Obviously, this had mixed results.

The Viennese production team for the 1967 Contest put together an interval show that was half a totally straight rendition of the Blue Danube and half an introduction to modern classical choral music. If you’re a Pink Floyd fan, you’ll see a direct link between the modern choral section of this interval performance and the choral sections on Pink Floyd’s 1970 Atom Heart Mother suite.

1968 saw the UK do a rather smooth montage of London tourist landmarks accompanied by a rather smooth orchestral backing, which was all clearly trying to portray some aspects of Swinging London and did so without scaring the horses. In 1969, the Spanish turned this format on its head and presented a baffled Europe with an atonal piece of modern classical music accompanying a video about the Ancient Greek elements. I cannot imagine how it went down in the rest of Europe, but I like to think that the British public was already used to settling down with Doctor Who and the challenging electronic music of the Radiophonic Workshop and took it more or less in their stride. It’s still a tough listen today.

It wasn’t all high art in this period. The 1970’s also saw what I’d argue was the worst Eurovision interval act – the veteran clown Charlie Rivel’s strange, over-complicated, horrifying operatic drag act is infamous. When I watched that video for the first time, the thing that really stayed with me was the grim, stoic expressions on the guests. They’ve just enjoyed some lovely, inoffensive light pop music and some fabulous outfits and now this. I don’t think it’s just me watching this through my 21st century right-on eyes – we had another opera drag act in the interval in 1991 that managed to skirt narrowly around the edges of being offensive – I think that Rivel’s clowning is genuinely a sad and unpleasant thing to watch.

But then, the UK booked The Wombles the year after, which surely meant nothing to anyone outside the British Isles. So everyone is capable of getting the interval show somewhat wrong.

1976 to 1978 – Jazz Odyssey

For some reason, and I am having a hard time working out why there were three straight years of rather good jazz ensembles providing the interval entertainment at Eurovision. This concluded in 1978 with France putting together an incredible jazz supergroup. Stephane Grapelli, Oscar Peterson, Yehudi Menuin, Kenny Clarke & Nils-Henning Ørsted Pedersen! That’s just showing off. But as swiftly and mysteriously as the jazz odyssey started, it finished.

1979 to 1993 – Variety In Three Acts

With massive musicals like Les Miserables, Cats and Miss Saigon in the theatres and a new wave of American dance movies like Footloose in the cinemas, you can see how the 1980s brought higher expectations of theatricality to the previously time-filling, unassuming interval act. Over the course of the 1980’s and into the mid ’90’s elements from the pop mega-musicals started leaking into the interval act – chorus dancers move from performing synchronous routines in matching outfits to individualised modern dance performances in slightly grungy costumes, the music they’re using gets flashier and poppier while still alluding to classical themes, and visual and special effects combine with traditional performance techniques.

The expanded role for the interval act now allowed it to incorporate international symbolism (see above, the Ballet for 12 Stars celebrating the 50th birthday of the European Union) and weave in technological elements (the multimedia Guitars Unlimited) but really we were back to the good old fashioned variety show.

There’s a trio of novelty acts that all astonish, for very different reasons. The 1984 ‘Art of Drawing’ physical theatre performance where a ‘drawing’ is animated with the help of some really skilful dancers would translate perfectly onto a modern stage and indeed, I saw something very like it in the national final season this year. The Swiss production in 1989 somehow turned the story of national hero William Tell into a couple doing an extensive display of crossbow skills. Set against howling 80’s synths and clad in white, puff-sleeved PVC bodysuits, the be-mulleted pair set up increasingly complicated stunts until finally, their big finish epically fails. Don’t worry, he doesn’t get shot in the head or anything, they just fail to split the intended apple. And finally, in 1991 the Italians decide to go back to the ‘parodic operatic drag act’ idea and give us Arturo Brachetti performing about a dozen of the great female operatic roles, between wonderfully executed quick changes. The act also contains what I think was the first occasion of implied nudity in the Contest, if you like that sort of thing.

Also notable in this period are two occasions in which Ireland knocked it out of the park in terms of their interval act – 1981’s TimeDance, which mixed contemporary and classical Irish dance and music to great effect, and 1988’s decision to just show the Hothouse Flowers singing ‘Don’t Go’ in various locations around Europe. It’s almost like there was some sort of cultural flowering about to happen, like Ireland was setting up for a golden period in the Contest.

Well, we all know what happened next. The video’s embedded – treat yourself.

After the initial exhilaration of the Riverdance sequence faded, I like to imagine the various heads of delegation around the Eurovision community having a moment where they realise that the game has now changed and you can’t just whack any old thing on during the voting any more. No, post-Riverdance the interval act has to be a paradigm-shifting extravaganza that shows off your nation’s heritage as well as providing a dazzling display of stagecraft and technological integration. ‘Oh,’ they thought. ‘Oh dear. How am I going to make our national dance into a world-striding colossus?’

1995 to 2000 – Riverdance: the aftermath

After it became apparent that Ireland had accidentally unleashed a genuine cultural phenomenon from the Eurovision Song Contest interval slot, there was a certain amount of ‘me too’. I remember being personally hurt and very disappointed that the Irish producers weren’t just showing us Riverdance again in 1995, which probably reflected the mood across a Europe gripped by Flatley Fever.

While we still had the modern musical theatre influences in our interval acts at this point, we were also getting a touch millennial and including themes of world harmony, progress, and peace depicted with increasing extravagance. Everyone putting together an interval act seems to have started with a central idea (a Boyzone song, a folk medley, the music of Gustav Holst, Dana International’s 2nd single) and then started piling on the extras until they ran out of time and/or money. This interval diversion started small, and it was getting bigger.

2001 to 2007 – New Millennium Contemporary Extravaganzas

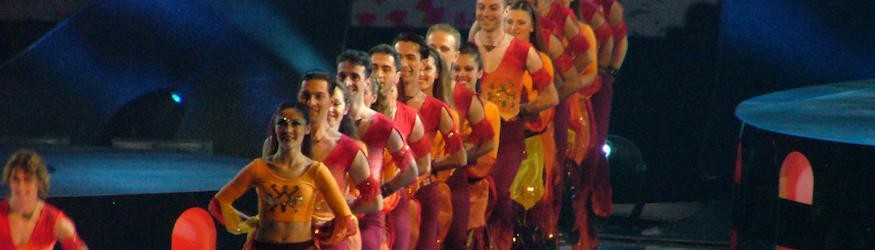

And the show just kept getting bigger and bigger. In this era, where the Contest has competition from the new wave of reality singing shows, the interval act responds by getting bigger and more outlandish. The extravaganzas become ever more extravagant. The numbers of dancers go up, the number of dance styles goes up, the stunts become more awesome. Then we start to build in crowd interaction, huge stadium lighting and pyro rigs and circus performers. It all comes to something of a head in Finland 2007, where a totally awesome scene of Nordic bacchanalia is enacted with shirtless members of Apocalyptica doing formation headbanging, while dozens of dancers and drummers and people banging on things fill the enormous stadium with noise and all manner of visual stimulus. What a show. How audacious!

The interval act had gotten big. Was it too big to fail?

2008 To Date – Smaller scale, Higher Concept

As you no doubt remember, between the 2007 and 2008 Contests, we had a financial crisis. Even though only Slovakia ended up withdrawing from the 2008 contest on specifically financial grounds, there were a couple of years with a prevailing sense of there not being a silly amount of money sloshing around any more. In Belgrade, instead of a cast of thousands being video-linked together into a musical theatre montage with pyrotechnic flying drummers, the Grand Final interval act was the awesome Balkan composer Goran Bregović and his band, and perhaps a couple of dozen dancers. Much more restrained than Finland and in fact probably the smallest scale the interval has been on since before Riverdance. I don’t think anyone minded. The sense of the stadium rocking out to Bregović’s music was palpable.

However, with the recovering economy and the general increase in the scale of the Contest overall, the scale of the interval act has started steadily creeping upwards again. We’re in search of a new paradigm.

We’re still taking influences from current trends in musical theatre and performance art. The Swedish Smörgåsbord in 2013 was an amusingly acidic humblebrag about the Swedish way of life which echoes Jerry Springer: The Opera in its flippancy. The 2009 Russian production brought in a wonderfully innovative Argentinian dance group, Fuerza Bruta, which might not have had anything to do with Russia, but looked pretty good and 2010’s Glow was able to really make the most of the concept of the flashmob dance number before it was used in every other advert or viral wedding video.

2016 – Justin Timberlake (and many, many more)

For Stockholm 2016, we’re seeing something new. The interval acts for the Semi Finals were self-contained and to the point – a self-deprecating skit about Swedish musical culture, a moving modern dance meditation on the refugee crisis and an enthralling dance-off between three humans and three alarmingly funky CNC robotic arms. All of these were highly effective at communicating a single artistic idea and managed to leave the stage before outstaying their welcome. The same can’t really be said for the Grand Final interval entertainment.

Sweden appear to have gone for a Superbowl-style multimedia tie-in approach to the interval for the Saturday night. We’ve got two pop singers launching new singles, Måns Zelmerlow with the underwhelming ‘Fire in the Rain’ and Justin Timberlake with his new song (written by Swedish pop grand masters Shellback and Max Martin to further demonstrate Swedish pop cultural supremacy), plus a superlative VT of ’42 Years of Swedish Music in 4 Minutes’, a highly entertaining song and dance number entitled ‘Love Love Peace Peace’ which will become your new all-time favourite Eurovision song, plus a handful of variable quality comedy skits which look like they’re the first things to chuck out in case of an overrunning show. This new smörgåsbord approach to the interval act is great for ensuring that everyone can get their plugs in, and makes the running order nicely modular, but I think that too much of it is of a lower quality than the rest of the excellent show. The Semi Final intervals were also much more artistically interesting than the commercial light entertainment for the Saturday night.

Mainly, I’d like to remind Sweden that Riverdance consisted of a short song and a three-part dance number, had a cast of under 3 dozen and had a running time of 7 and a half minutes including the standing ovation.