Geography isn’t the kind of subject where you can learn a page of formulas or a general method and expect the rest to follow naturally. Subjects like geography and history must be learned by presenting yourself with large amounts of information and hoping that they’re memorable enough to sink into your brain and also structured enough to form a coherent narrative.

There isn’t a single rule of thumb that tells you where the boundaries of all countries are or what type of language they speak there or what their culture is like. You’ve just got to learn. For most people that’s impossible to do by rote, and they need a bit of help.

The greatest of all accidental geography teachers is the Eurovision Song Contest.

Donde Esta Harrogate?

Geography is a subject that isn’t the main focus of education. In several EU (and EBU) countries, you aren’t compelled to study geography at all in the later high school years. The best pan-European data available shows that average amount of compulsory study time for all the humanities combined (geography, history, citizenship, philosophy and social and political instruction) is under 100 hours per school year, out of around 1000 hours of total school time (Baïdak, N. and Ubaghs, J. (2015) ‘Recommended Annual Instruction Time in Full-time Compulsory Education in Europe 2014/15’).

Everyone loves a good flag-off, even at Junior Eurovision (image: Sharleen Wright)

So, let’s say we’re devoting fifty percent of our hundred hours of humanities to geography for the last two years of school – and if you were focusing purely on human and political geography – you’d have to get through just over four countries per hour to introduce each of the 206 sovereign states in the world (as listed by the UN). Fourteen minutes? That’s barely enough time to flash up the map and flag, name the capital city and two most important exports. No time to talk about how that country relates to its neighbours, how it relates to its past, how the people live or even if there are any interesting mountains.

So even if a teenager doesn’t decide that she would better be served by learning about business studies or studying an extra science subject, your average school-leaver will probably not have been presented with sufficient geographical facts to give them an idea of their place in the world, or a context for events in the news – or even make them any use to your pub quiz team.

Luckily for us, popular culture contains a few different transmission vectors for various kinds of basic geographical knowledge mixed with entertainment – you’ll no doubt be familiar with the kind of documentaries where a celebrity (at one point for the United Kingdom it was always the glorious Michael Palin) travels around the world, telling you about physical, environmental and human geography at various levels of detail.

Zeroing in on Europe, you could get your supplementary knowledge of geography by going inter-railing through all the states, or you could get an in-depth knowledge of the characters, locations and climates of various European cities through following the vagaries of the Champions League. You could even be introduced to geographical facts via stamp collecting or coin collecting. But I don’t think these hobbies can hope to mix as much geographical context in with entertainment and enjoyment as you’l find in the Eurovision Song Contest.

Where Is Harroaget? (EBU/BBC)

A Confluence Of Sound

When the Song Contest started, it was part of a deliberate pan-European effort to foster peace and build understanding after the horror and disaster of the Second World War. If you hear the music of another country, hear them express love and hope and joy in their own language, and see that they are essentially just like you, then how can you raise weapons against them, plan to exterminate them or drive them out of their land?

Because the early Contests were designed to show off the technological marvel of live interational broadcasting, there was usually an additional element of geographical and touristic information built into the role of the host country – if you’ve got the opportunity to show off that you’re broadcasting live from somewhere distant, why wouldn’t you?

Since 1959 the basic format of the contest has tended to include a location establishing sequence of the host city. This sequence is also often a technological demonstration – with 1950s TV cameras & broadcast technology even the slow, blurry pan across the bay at Cannes that launches the 4th contest must have been quite an undertaking. Indeed, it was apparently deemed such a good idea that they repeated exactly the same introductory shot of Cannes in 1961 with a slightly more effusive narration.

As TV making techniques developed, the scene setting sequences got more elaborate. London 1963 started the contest with the now familiar routine of zooming into the venue from the wider cityscape, including a flypast of BBC Television Centre from a helicopter, which must have been exciting to pull off. The scene-setting sequence disappeared for a couple of years after 1968, when the Contest went to colour, but returned for a lengthy, evocative tour of Amsterdam in 1970.

Terry Wogan’s scripted introduction to the 1973 Contest informs us of the two major industries of Luxembourg, which is a solid bit of schoolroom geography right there. His later introduction to Dublin 1981 is a bit more relaxed, but still shows us the stunning physical and human landscapes of Ireland. We’re still innovating with the geographical scene-setting – the parade of national flags into the arena that started in Malmo 2013 (which itself had been lifted from previous Junior Eurovision presentations) might not stick, but it’s already provided some memorable imagery (as well as some helpful flag revision time).

Once we’re firmly located in the context of our host city, the video ‘postcards’ which have introduced the songs since 1970 usually contain a solid thread of geographical information running through the theme, even if it’s just creative ways of displaying a national flag, or interesting touristic landmarks around the host country. I think my favourite set of informationally dense postcards might be Moscow 2009, where Miss World represents notable buildings from each country as a series of deeply surreal, imaginary hats. [

Good Evening This Is Tallinn Calling

It’s only been with us since 1994, but how familiar and yet how exciting is the voting routine? And how geographical is it? When each country delivers its vote we get a map graphic (which has deployed increasing amounts of razzamatazz as computer graphics improves) and usually a flag graphic, plus a local celebrity standing in front of a famous landmark. I hypothesise that the emotion, the repetition and the whizzy graphics of the voting sequence make it a brilliant aid to study. By building up this chain of associations at an emotionally intense time – the flag, the map, the city, the landmark, the douze points – we increase the chances of the facts becoming retrievably lodged in our memories.

If I were to test you with moderately taxing geography quiz questions like ‘What is the capital of the country with this flag?’ and ‘What is the northern neighbour of the country represented by this map outline?’ I believe that Eurovision fans would perform significantly better than non-ESC fans.

Building Bridges

The scoring relationships between Eurovision countries – diaspora voting, bloc voting, and even bloc non-voting can tell us about movements and tensions in Europe.

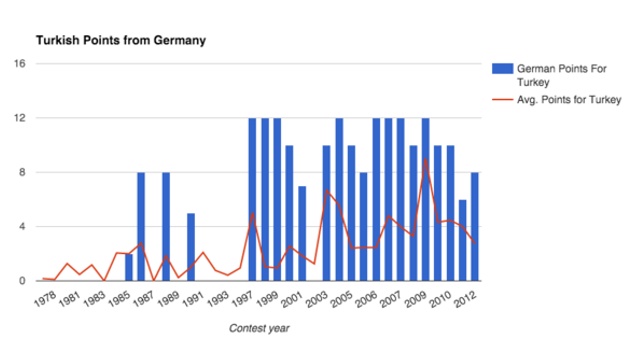

Let’s take the often cited example of the Turkish diaspora in Germany. The graph below illustrates the era of scores being decided by public televoting, Germany awards significantly more points to Turkey than the mean points awarded by all other countries. Out of the 19 opportunities for the German public to award final or semi-final points to Turkey, they beat the average score 18 times, with 8 of those being the maximum 12 points. You could argue that Turkish diasporic voting from all around Europe led to their strong performances in the 100 percent public vote era of Eurovision. Bolstered by their diaspora, they did well with some really culturally Turkish songs at a time when other countries were moving towards a more homogenized pop approach with less national character.

Turkey / Germany diaspora points

The reciprocal and non-reciprocal scoring relationships, once you notice them, can lead you to think about why that might be. Diving into the history and geography of a scoring relationship can illustrate the effects of political disagreements and long-standing international relationships which can otherwise be quite abstract and drily political. If you’re interested in looking into the relationships further, two UCL academics produced an extremely interesting analysis (Blangiardoa, M. & Baiob, G. (2014) ‘Evidence of bias in the Eurovision song contest: modelling the votes using Bayesian hierarchical models’) which shows that no Eurovision country has a particular enemy, but that many Eurovision countries have particular friends.

I think that can only be a very reassuring finding, because in this contest we’re supposed to be bringing Europe together, and not highlighting the faultlines and amplifying discord.

A Modern Fairytale

Personally, the biggest geography lesson that the Eurovision Song Contest has given to me is that the more I learn about places through their music, the more I want to visit. I haven’t yet been to Estonia, but I feel like any country that puts Winny Puuh on television and suggests this might compete sensibly with a lady singing a ballad in a white dress definitely has something going on that I want to find out about. You might never have previously considered visiting Montenegro before watching the Song Contest, but the 2015 combination of Knez’s lilting ballad with images of stunning Montenegrin landscapes might have had you planning a trip.

As Eurovision enthusiasts, you’ve almost certainly got your own tales of discovery and travel that link back to the Contest. It’s a wonderful thing that these three evenings of light entertainment once a year can help broaden horizons, inspire hearts and open minds.

Long may it continue.

I didn’t even get into the way that the contest leads to discussions about what the definition of Europe is, and why that’s interesting but not actually that relevant to the contest.

Great piece, Ellie!

Here in Seattle, with the aid of a large National Geographic map standing next to the projector screen, a whole horde of Americans have got to grips with all sorts of Euro-geographical and -cultural minutiae, and some of them are even beginning to remember ISO-3166 2-letter country codes (thanks to post-its on the map). Australia is, however, causing cartographical issues.

And as Oscar Paradise (FI, 2011) tells us, “Peter is smart/He knows his European countries by heart.” Evidently, Peter has been absorbing it all through years of ESC watching…

Keep the over-analysis coming. 🙂