Previously on ESC Insight, we took an academic look at how the public judge entries in the Eurovision Song Contest. Now it’s time to turn our attention towards the other half of the scoring process at Eurovision… the jury vote.

This article is going to talk about how juries work; the thought process of individual jurors; and how elements such as the running order, national bias, ill-defined guidelines, time constraints, and a lack of training all impact on the jury results.

One question you might ask is ‘why go to all this trouble, it’s just a television show?’ And I think that’s the issue. The Eurovision Song Contest is more than a television show. As the EBU remind us, it’s the largest entertainment show on earth, it’s the largest singing contest, and it was set up to not only as a technology test-bed, but also to help bring together a continent ravaged by war and distrust. If you are organising a Contest with that sort of scale and history, part of the remit should be to provide a fair and neutral platform for everyone to compete on. That is why this is an important topic.

Why Do We Need To Look At The Juries?

Since 2009, the national juries have made up 50% of the final vote awarded by each broadcaster at the Eurovision Song Contest. While many Eurovision pundits pour over the running order and the on-stage performances to try and ascertain what the public will make of them, the impact of the jury does not receive as much attention. In many discussions you might hear ‘the jury will go for that’, or ‘that’s one for the juries, the public won’t vote for it at all.’

The current jury system has a number of flaws that have the potential to introduce unwanted bias into the final result of the Eurovision Song Contest. These flaws are well documented in other judged contests, and the EBU should look to them to help improve the jury system for the Contest.

The Eurovision 2011 Winner… according to the juries.

It’s important to highlight that the juries are human, and will be affected by the running order and the presentation in exactly the same way as someone watching the show on their television at home. Our key findings (from ”) can be summed up as…

- The producer led running order includes a remit to program ‘genre’ songs away from each other so they can ‘stand out’, which assumes the audience is using a contrast model of comparison.

Mussweiler, T. 2003, Comparison Processes in Social Judgement: Mechanisms and Consequences (Psychological Review 110 (3) 472-489).

- Academic studies show that people evaluate songs by comparing them to the previous song, comparing similar elements to decide which is the better song… an assimilation model of comparison, the opposite of the model adopted made by the production team.

Drs Lionel Page and Katie Page, A Field Study Of Biases In Sequential Performance Evaluation On The Idol Series (Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization (2008).

How The Juries Will Work At The 2013 Song Contest

As in previous years, the juries will assemble to watch the second dress rehearsal of the two semi-finals and the grand final on the night before the live show (Monday 13th, Wednesday 15th, and Friday 17th May 2013). Their votes must be submitted by 2300 CET that night, which means that they can watch the show just the once before deciding their rankings and submitting them to the official voting partner, Digame. There will be no official opportunity to listen back to songs and watch the performance again, perhaps to run two similar songs against each other to see how they compare, to check for vocal flaws, or to simply remind themselves in full of a song from earlier in the running order.

This leaves the five member juries open to the same running order bias issues that affect the public. But remember that the public are simply asked for their one favourite song, while this year the jury are being asked to rank every single song that they hear to come up with a ‘1 to 26 order’, where every position will be important in the final result. Objectively that’s a much more difficult task, made doubly so by the time pressure the jury members will be under.

What Information And Guidance Do The Juries Receive?

So what do the EBU actually ask of the jury members? There are two areas to look at, the process and the criteria.

There are extensive details on the technicalities behind the voting, detailing the process that happens between broadcasters, jury heads, the jury members, and Digame. The EBU places guidelines on who should be in the jury, and advises on the timing, and the process of submitting individual juror’s rankings digitally to Digame.

Jury members are asked to rank the songs from 1 to 26 (or 16 and 17 in the two semi-finals). On the ranking form provided to each juror, they are asked to focus on a number of areas. Following a similar process to previous years, for the 2013 Eurovision Song Contest the EBU will be asking all jurors to focus on the following areas:

- Vocal capacity.

- The performance on stage.

- The composition and originality of the song.

- The overall impression by the act.

This is a good start by the EBU (and it’s worth pointing out that contrary to the belief of many, the EBU does not consider ‘commercial success’ a valid criteria), but if the purpose of the jury is to balance out an impulsive public vote, then the current methodology is not sufficient, as the juries are also open to the same impulses.

Running Wild, Running Free

That’s not to say that the jury are not aware of these issue. EscXtra’s Luke Fisher served on the Jury during the Austrian National Final this year, and Fisher felt that he had a duty to balance out the expected views of the public. “Whilst ORF did not give us any guidance on how to vote, merely ‘to rank them in order of preference, I did feel a responsibility to balance out my votes with how I expected the public to vote,” Fisher told me. “I felt that I should ‘vote up’ a song that I thought wouldn’t appeal to a televoter but deserved to do well”.

There may be a list of areas to focus on, but without guidance from the organisers, jurors are left to decide their own criteria for voting, to add in their own personal thoughts on what areas should be compensated for, and if they should take a personal view of each song from their own viewpoint, or how the song fits into the wider musical industry.

The impact of how jurors judge can be minimised with clear and defined instructions from the EBU. This is a process that other competitively judged contest already employ. One clear example is in the Word Figure Skating Championships.

Looking at the protocols of between 1994 and 2000, the selection and training process is clear. Nine judges are selected at random from an international pool of judges (with the caveat that each judge of the nine must come from a different country). All of the judges in the pool “receive extensive training to achieve high-inter-rater reliabilty, had years of world-level jury experience, and were continuously checked for nationalistic bias.” (Weekley, J. A., & Gier, J. A.,Ceilings in the reliability and validity of performance ratings: The case of expert raters (Academy of Management Journal 1989, 32, 213–222).)

Bolero, Bolero, where the sun is always shining on you…

Further studies by W. Bruine de Bruin (Save the last dance for me: unwanted serial position effects in jury evaluations. Acta Psychologica 2005, 245-260) show up a few more points that I feel are relevant to the Eurovision Song Contest.

The first is that through the training and input from the International Skating Union (the ISU), neither the final scores or the individual juror scores exhibited national bias (de Bruin p256). But this training did not eliminate any bias because of the running order and the serial nature of judging.

Figure Skating relies on ‘step-by-step’ voting, with each contestant receiving their score directly after competing. Other judged sports and contests rely on end-of-sequence procedures, where the scores are allocated after all the competitors have performed. Both methods show a similar linear order effect giving competitors at the end of the contest higher scores.

In other words the running order still impacts on the results from a professional jury, even with training and strict criteria.

How To Make A Fairer Eurovision Jury

The jury system for the Eurovision Song Contest, while technically detailed, lacks the strong direction and rigour that other judged contests have. But with a few changes backed by academic research, the confidence in a jury vote could be improved.

Guidance and training

Firstly the EBU need to supply more guidance to the jurors so they can make informed decisions. Rank the songs from top to bottom, with four criteria to consider, leaves a lot of room for interpretation. There’s an argument that being this hands-off allows jurors to use their own skill and judgement to rank the songs, but there needs to be a distinction made between telling the jurors what to vote for (which we don’t want), and what the jurors should be looking for (which is currently left as an exercise to the individual).

The EBU focus heavily on the technical process, and that same focus and detail needs to be employed to the psychological process of voting to reduce the human bias that currently unbalances the system.

Reducing the impact of a lone voice

The current juries consist of five jury members. That’s a huge amount of voting power handed to one person, and the impression is they hold 10% of the overall mark. In fact they have a much larger impact. The new scoring system, where jurors are asked to rank all the songs, will reward songs that have a consensus opinion. A song that divides opinion, with some jurors voting it highly, with others ranking it low, will have a lower score a song which is ranked ‘middle of the road’ by everyone. A single low ranking in a jury of five members can have a significant impact on the final jury ranking.

I would increase the number of jurors to at least thirteen jurors, and preferably out to the same number of songs that are performing in the Grand Final. The more members on a jury, the less damage an outlying opinion can have. And if you have a larger number of jurors, the third recommendation becomes even more potent.

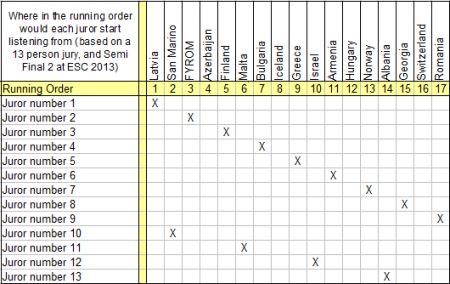

Give every juror a different running order

While it is desirable to guide each juror in an attempt to minimise bias, it is also possible to create a level playing field with the running order if you have a large enough pool of jurors. There is no need or requirement for the jury to be entertained, their job is to judge the songs. So why do they need to watch the regular show as the audience do, why do they need to watch the postcards, and why should they watch the same order of songs as the public?

If you have twenty six jurors, every song can have the opportunity to ‘open’ Eurovision, every song gets a shot at closing the Contest, and every song gets a go at being second in the order.

Twenty six is rather unwieldy though, so you could get the same effect with thirteen jurors, and an equal spread of the starting positions for the Grand Final – juror one starts at song one, juror two starts at song three, juror three starts at song five, and so on. For the semi finals the ‘extra’ jurors after this process would also be equally shared out, starting their viewing at every third or fourth song.

Using this method, every song has an appearance at the weaker and stronger points of the running order, and the effects occurring from the running order bias are shared out equally between all competitors.

Which song would be the ‘first’ song for each juror in an offset system?

This would mean that some jurors would not be able to start the judging process until later in the proceedings, which would mean the deadline for submitting a ranking to Digame would need to be extended, but remember this happens a full day before the live show that the public vote on, so there is clearly enough time to accommodate this. And the benefits to the integrity of the jury vote far outweigh the issues in delaying Digame’s collation of the jury result by an hour or two.

Give the jurors more time

Finally, jurors should have enough time to rewatch any song to refresh their memory, to compare two songs next to each other, and not have to rely on their memory to compare a song near the end of their running order to one that they listened to over ninety minutes ago to minimise any remaining serial order bias. Currently the final rankings need to be submitted via Digame to the EBU by 2300 CET. In previous years the deadline has been 0900 the following day, and it would make sense return to this schedule.

Final Thoughts

The 50/50 split between the public and the jury was introduced in 2009 following disquiet at the diaspora influence voting patterns under the 100% tele voting system.. The current system goes some way to reducing national and cultural bias, but introduces unnecessary human bias into the result. Thankfully there is a lot of scope to improve the process. Four small changes should be considered for the 2014 Song Contest, and beyond.

- The EBU should introduce training and evaluations for jurors to reduce bias, and provide clearly defined judging criteria and instructions.

- The number of jury members should be increased, potentially to thirteen members (half the number of songs in the final).

- Jury members should watch a personalised and edited version of the Contest to reduce the overall impact of the running order.

- The deadline should be extended to allow jury members an opportunity to re-watch performances.

The Eurovision Song Contest is the biggest competitive singing contests in the world. Yes it is a huge light entertainment show that can rival the Superbowl half time show in spectacle and viewership, but it is still an international contest, one of the largest in the world. With that status comes a responsibility to create a level playing field for every contestant and to have each song judged in a fair and equitable manner. With some small changes to the jury system procedures, we would have a fairer Contest.

And that is, surely, an ideal to strive for.

Perhaps figure skating isn’t the best comparison since the running order nowadays has little to do with outcome. Or at least that is what the ISU claims. The reason being no less than three socalled technical experts who guide the actual judges as to how much they can value a certain jump or move. That would be funny at Eurovision if a technical expert could put the kibosh on, say, Russian grannies who couldn’t sing worth a damn but instead bake cakes on stage; or tell a juror that he or she may only award Serbia 3 points considering that all three girls are off-key. Ironically, the old figure skating judging method, the socalled 6.0 system, demanded that the judges rank each skater in each part of the competition, which resulted in chaos in a field of 30 or so competitors. The new (2004) system did away with that, and in qualification rounds judges can sometimes be forced to sit through 40 programs. But I digress …

Good points, and 40 or so programs, compared to 39 Eurovision songs isn’t that bad. Perhaps we should send the ISU to the Maltese semi final?

The point on singing off-key is an interesting one though. In the ISU model there is a penalty, but in the current EBU model, it’s up to the jurors if they should penalise an off-key singing, or if holding a tray of cakes is a mitigating factor.

And of course Jon Ola Sand has stated that “there is indeed no significant statistical impact of the running order on the result.” So lots of commonality there.

Do the five jury members watch the contest together? Or do they watch it separately? I wonder if they’re swayed by each other, or if they vote in complete isolation.

A big difference with jury and televote will be that while people watching at home can go out to the kitchen and make tea, or go over to another channel is they find a song boring, juries are not, they actually have to sit and watch the whole thing through and pay attention.

They watch together, but I don;t think there is officially meant to be any conferring.

Some points I agree with and others I don’t. My main concern here is the efficiency and cost effectiveness of your ideal jury system, Ewan. The impression I got is that you would like jury members to have more clearly defined guidelines and criteria with which to cast their votes, which I definitely agree with. On the other hand, each jury member, especially with a number as high as 13 of them, watching a personalised edit of a dress rehearsal demands either 13 separate screenings of said dress rehearsal, or a number of rooms with a number of televisions, forcing each juror to vote in isolation. While I understand your point that the jurors have a job to do and do not need to be entertained, I fear that what you describe might be overstepping the line a bit, heading towards making the job overly scientific and even clinical.

While I agree that the Eurovision Song Contest is a production of some magnitude and great cultural importance, I believe it should primarily try to be an entertainment television show that should focus on improving its “pop” credentials while still standing up for quality music in contemporary, traditional and more artistic experimental senses and of course, cultural equality, free speech and unity across the continent. I don’t believe it should be considered as “high class”, for want of a better phrase, as the World Figure Skating Championships or the BBC Proms – and I’m also inferring it certainly should not be judged as such, both internally and in the media, either.

My point is, I don’t see any need for jurors to judge the contest in radically different ways than the public *could*. The emphasis being for the sake of pointing out that generally speaking, only fans go further than simply watching the shows once, but anyone could go further, since the songs are made publicly available well in advance. Hypothetically speaking, if everyone did, I’m sure the manner of the televote would be very different.

I think the jurors should simply be asked to familiarise themselves with all the songs before arriving for duty in May, and they can do this easily enough through YouTube. I would say guidelines should state that jurors should only begin to do this after the HoD meeting in March when final versions are handed in, but there should not be anything to stop them from getting ahead of the game and joining in national final season as the fans do, if they so wish. If they are familiar with the songs and have pre-conceived ideas about each one, then the psychological effect of the running order should, in theory, be drastically reduced without any need for individual isolation, personalised edits and extra time to re-watch performances. This would also help jurors to compare the quality of the compositions and the quality of the live vocal performance separately.

Broadcasting the exact same programme to each panel in each country at the same time, live from the host city is also much more efficient and reliable for the EBU, as some television stations may attempt to corrupt their juries when handed the discretion to show personalised edits. The best example being the Armenia-Azerbaijan voting scandal of 2009. Who knows? One television station might even have the balls to try getting away with broadcasting a personalised edit to the pubilc! Even developed countries such as Spain are not beyond failing to broadcast programmes to the public at all in favour of sports matches overrunning or heaven forbid, national tragedies occurring. We’ve already seen that some things are simply beyond the EBU’s control, and written regulations aren’t always enough to prevent that, therefore the EBU needs to retain as much discretion and freedom to complicate procedures and broadcasts as possible for the sake of both efficiency and fairness.

Every time I hear someone say the juries always go for the ballads, I think it’s mainly down to the vocal capacity.

However, I do think the ‘vocal capacity’ section is probably the most important of the 4 categories. After all, it IS a song contest we’re on about!

But in order to win the Eurovision Song Contest, they’ll need to have the complete package which meets those 4 categories from the juries AND hope the televoters agree.

Interesting article Ewan. I’m not sure though I agree that jurors are “affected by the running order and the presentation in exactly the same way as someone watching the show on their television at home”. I would expect that a lot of the jurors would already be more familiar with the songs than the televoters, and even if they aren’t, they’re surely taking notes throughout the show, so won’t be affected in “exactly the same way”. And as such, I think making them all watch a different running order would be a complete waste of time.

I agree it would be nice to have a few more jurors than five, though probably not as many as you think there needs to be.

And whilst I agree that it’s not just a TV show, I don’t think it’s necessary to go to such lengths just to make a few minor changes in the overall results, when really it’s all about the winner anyway.

BTW surely they will be voting 1-25, not 1-26 😉

Keep up the good work team and really looking forward to the return of the daily chats!

I agree about Jury size. I’ve been saying this for years. Small sample sizes tend to yield random results. When you consider the process of jury selection, and those en-tasked to pick people, all kinds of possibilities for eccentricity in a 5-person panel spring to mind.

What you don’t address is (IMO) a key “justification” for the juries: i.e. to mitigate the advantage of songs that look/sound great on one viewing, but quickly fade, as compared to those that those that have more durable appeal. The value of instant impact is already well represented by the televote. I wish there was a requirement that the juries were thoroughly familiar with the songs before finally judging their live performance (which is, I assume, already the case for many jury members – it would be if I was one of them).