So you’re getting ready to produce the Eurovision Song Contest! Do you want to make a competition or do you want to make entertainment?

Most shows have an obvious bias one way or another —‘Match Of The Day’s’ FA Cup final coverage leans into showcasing a competitive product whilst ‘The Royal Variety Performance’ is geared towards pure entertainment. The dilemma for the show producers of Basel 2025 is that, at its essence, the Eurovision Song Contest needs to be both.

Is It A Contest Or A Show?

Find any definition of the Eurovision Song Contest, and the noun used to describe it will almost certainly be “contest” or “competition”. This is an essential aspect of Eurovision’s identity. No matter which edition of the Song Contest you watch, there are always points awarded, there is always a final ranking, and there is always a winner (plus a hard stare at 1969).

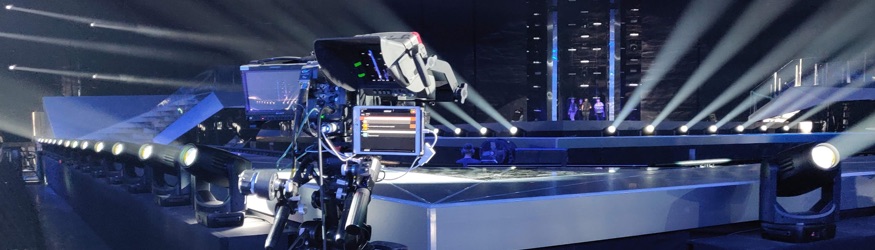

What isn’t always emphasised is that, fundamentally, the Eurovision Song Contest is a television show. Every Edition has been televised live internationally, and the show has represented a unique opportunity for host broadcasters across the continent to share best practices in TV production with the latest cutting-edge technology available to the production.

In 2024, Contest Producer Christer Bjorkman introduced a series of changes to the Song Contest aimed at crafting Eurovision as a better show. This brought the balances, contradictions and possibilities of these two diametrically opposed but equally important sides of Eurovision into sharp relief.

Entertainment And The Producers’ Choice

It would be remiss to start anywhere other than the running order when discussing producer influence on the Eurovision Song Contest result.

When it was announced that Eurovision 2013’s running order would be selected by producers, following a draw to determine if each act would be placed in the first or second half, it elicited mixed reactions.

Whilst the random draw aspect still gave a degree of chance to an artist’s running order slot, it meant that the show’s producers were now intentionally choosing which songs to boost by putting them in historically competitive positions versus which songs would be hampered by doing the opposite.

With the introduction of the Producers’ Choice category to Malmo 2024, the slips in the running order pot consisted of a quarter that represented the “first half”, a quarter for the “second half”, and everything else as “producer choice”. This gave the backstage team a significantly greater degree of influence over the show.

This meant that when televote favourites such as Ukraine and Israel (both of whom drew Producer’s Choice) were given early slots that followed visually bold energetic numbers (Sweden and the Netherlands) the production choices were leaning into the “as a TV show” rather than “as a Contest”.

In doing so, it also reduced the chance associated with the draw process, biasing certain songs over others.

Competition Disrupts The Spectacle

Few of us would argue that Malmö 2024 didn’t flow well as a show. The colours, genres, styles and energy levels were spliced perfectly between the songs to allow each of them a relative opportunity to contrast with the songs it was immediately around—a classic trope of Swedish-styled running orders).

It’s also true that previous shows (both before 2013 and 2024) have suffered from draws which left a number of similarly styled songs next to each other to congeal in a manner that was either too energetic (diluting the musical styles) or too slow (causing audience members to get bored). It’s undoubtedly clear that more significant producer influence means more likelihood of a smoother and better-balanced show. How can the competition be a level playing field when producers make decisions that bias certain songs over others?

Is it worth sacrificing competitive integrity for an entertainment programme which has the word “Contest” in its title?

For all the reasons that the producers’ influence has affected the competitive aspects of Eurovision, other production choices have been similarly impactful the other way.

A maximum of six performers on-stage creates significant limits on staging for upbeat songs as artists are asked to choose between dancers, backing vocalists and the visual spectacle associated with a busier stage. The limits around autotune have also defined Eurovision away from what is increasingly considered best practice in live music contexts.

And then there’s the points sequence, an iconic facet of the Eurovision Grand Final but aside from interval acts that are necessary to facilitate a period for televoting, is still arguably the least entertaining section of the entire show. In a world where a 4-hour TV show is undoubtedly long and Eurovision is increasingly pitched as a family show, could an amalgamated jury presentation (much like the one trialled at Junior Eurovision in Madrid) create a shorter and more attractive TV show?

On to Basel

Wherever your opinions lie on this spectrum, it’s clear that there are two very different extremes that the Eurovision Song Contest has to balance.

On one side is the argument that, by and large, a Eurovision Song Contest should feel like the same kind of product every year. That means the same rules, mutual understanding of the circumstances for artists, delegations, jurors and televoters and a focus on protecting Eurovision’s competitive integrity.

On the other side is the argument that as an internationally-renowned TV show hosted by different national broadcasters across Europe producers should be given artistic freedom to craft the TV show that best fits their channel’s style, audience and vision for what the Contest can and should be.

These are, as mentioned, the extremes. Much like any form of politics, it’s a choice that those with the power have to make based on what they think is best at the current moment. It is important, however, as we look forward to Basel 2025 that we recognise that the relationship between Eurovision as a competition vs. Eurovision as a TV show is a complicated one and that any choices made specifically to favour one side will almost certainly have a huge effect on the other.

Malmö 2024 threw up a huge number of questions about the values, priorities and identities of the Eurovision Song Contest. In May, the team behind producing Basel 2025 will have a fresh opportunity to address the balance between the competitive and entertainment sides of one of the world’s most popular TV shows.

With opening numbers and intervals, the producers can promulgate all the entertainment they desire. But the further the Contest moves from random assignment of draws, the more open it is to bias.