One thing distinguishing Melodifestivalen from the other selection shows around Europe is the nature of the multi-episode format. For six weeks, the show parades itself around Sweden, bringing the whole country together in arenas from its southern tip to its northernmost outpost to share in the country’s biggest TV spectacle.

Sweden’s public service broadcaster can not do this alone. The tour is a co-production between SVT and private companies All Things Live and Live Nation. Live Nation is the biggest organiser of events and concerts in Sweden, organising 2000 events that reach over one million Swedes annually. They are responsible for the commercial wing of the Melodifestivalen tour, promoting and selling thousands of tickets three times a week as we go around the show. All Things Live is responsible for much of the tour logistics, taking the flat-pack stage round the country and keeping the show on the road.

LIAMOO backstage at heat 2 of Melodifestivalen 2024 (Photo: Stina Stjernkvist, SVT)

To learn more about how the show manages to pull off the tour, I spoke to Tobias Åberg, SVT’s project manager for the Melodifestivalen production.

Tobias is one of the most experienced names in the world of the Eurovision Song Contest. With a career’s work in the live events industry at gigs and concerts around Northern Europe, he first set foot on the stage at Melodifestivalen in 2004, working with the staging team. Since then, he has worked on numerous editions of Melodifestivalen and first held his current role in 2014. However, he has also been part of the core production team at various Eurovision Song Contests, including Sweden’s last two hostings in 2013 and 2016, as well as contributing in 2017 and 2019 and working with the BBC on producing our most recent Contest in Liverpool.

Tobias will also be part of the core team for the 2024 Eurovision Song Contest, responsible for the technical structure and the implementation of the Contest.

Tobias Åberg (right) with other members of SVT’s leadership team for the 2024 Eurovision Song Contest (Photo: Anders Strömquist, SVT)

His work at Melodifestivalen is not by itself full-time but does operate beyond the six weeks of the year. For example, each spring, Tobias starts co-ordinating the tender contracts for next year’s show, and in the autumn, once the songs and artists start getting selected, the collaboration with the creative teams begins.

The job, of course, ramps up as we get into Melodifestivalen season. The week-by-week routine that Melodifestivalen falls into is one where, as soon as the broadcast is complete on a Saturday evening, the tech crew works to dismantle and pack away the stage. This tends to take four to five hours, meaning the crew, on average, depart each venue around three in the morning. Sunday is a travel day, where roughly ten trucks depart one arena and head to the next. Monday and Tuesday are dedicated to building the set in the arena before Wednesday, giving the team a chance to run dry rehearsals before the artists arrive on Thursday to perform in front of the camera.

Only a select few of the team follow the tour for the whole six-week stint, with Tobias explaining that the creative teams from SVT normally arrive on location on the Wednesday of each week.

The Challenges Of Different Locations

Tobias points out that while the flat-pack stage might be the same from week to week, that doesn’t mean that the set-up is identical as the tour navigates around the country, as Tobias Åberg explains.

“The big difference between a normal music tour compared to this is that [on a tour] we do more or less the same show each time. At Melodifestivalen the whole content is different, with different songs and different content.”

This means there is much more rehearsing time around Melodifestivalen than what you would get in the other parts of the music industry to ensure each number can work to perfection.

The other dilemma that the team have to deal with each week is that Melodifestivalen has to adapt to different arenas. For most of the weeks of the Melodifestivalen tour, the show is held in some of the various ice hockey arenas that Sweden has a plethora of, which all roughly have similar dimensions. However, the fourth heat of this year’s show came from Eskilstuna’s Volvo CE Arena, which is an international-class handball venue, a sport needing a 40 m x 20 m floorspace compared to ice hockey’s 60 m x 30 m.

The smaller dimensions in Eskilstuna mean minor adjustments to the studio setting on this leg of the tour. The smaller floor space means that the lighting team has been moved into the stands, so there is still space for the Green Room at the back of the arena. Look carefully at the LED ‘wings’ of the Melodifestivalen stage for this heat, which is tucked in behind the performance area here in Eskilstuna to get the stage to fit as seamlessly as possible.

The opposite problem occurs when the tour finale hits Friends Arena, that Sweden’s national football stadium hosts 30,000 people each year. Tobias recognises that, compared to the Eurovision Song Contest, it can be a “struggle to get atmosphere” in Friends Arena, with many fans much further from the stage and a wider range of fans ranging in age for the family entertainment extravaganza that Melodifestivalen is. However, SVT has been present at Friends Arena for this show since 2013 and has developed some “tricks” to improve the atmosphere there. One example Tobias gives is of how the team has spread out the audience microphones around the arena much further to pick up as much of that buzz as possible.

Twenty Years of Sustainability Progress

Tobias highlights that one of the biggest differences with Melodifestivalen now compared to when he started is that there is a much larger focus on sustainability in all aspects of the production. For example, there are increasing efforts in terms of stage design and equipment to ensure that less space and less weight is needed, reducing fuel costs as equipment is transported from year to year.

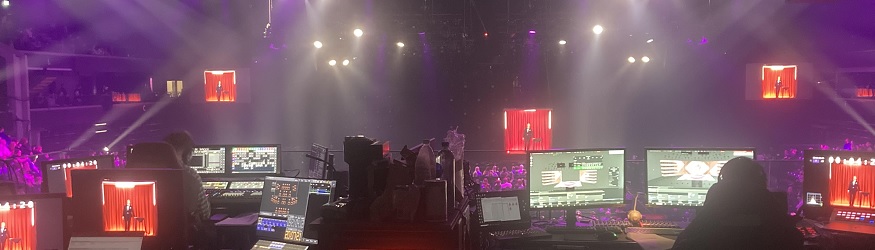

Tobias notes that this year, the show uses a smaller and lighter PA system that follows the tour, the L-Acoustics L2 system, which claims to reduce truck volume by 30% and weight by 25% compared to equivalent PA systems. Melodifestivalen is one of the first productions in the world to use this new piece of kit after trials last year, having before been employed at the BRIT Awards, Coachella and Helene Fischer’s tour, and it is also planned to be used at this year’s Eurovision Song Contest in Malmö.

Another new feature for this year is that the 2024 Melodifestivalen production only uses LED fixtures, rather than discharge lamps that were the industry mainstream but have considerably higher energy usage. In theory, this should be the sustainable option, but one danger with LED technology is that heavy usage can see the colours deteriorate, which is one reason why their use has been limited until this year. Tobias notes that even “if you go back three years, we could not do this show with just LED lights”, so far has the technology come recently.

Sustainability isn’t the only part of the technology that is different nowadays at modern Melodifestivalen. Tobias describes modern-day production as “more precise”, mainly in part to how the show works with LiveEdit. This production tool allows automated processes to be created for live events, allowing for far more accuracy to be obtained in each run-through and more rapid camera changes if requested. Choosing between LiveEdit and CuePilot, a program first used at Eurovision in 2013, was decided via the annual tender process based on a balance of cost and the tools provided.

Tobias also names Notch as another weapon in the production arsenal at SVT. Notch is a real-time graphics tool that adds effects to live pictures. An example of this being used came in during last year’s Melodifestivalen, where in Kiana’s ‘Where Did You Go?’ dancers moved LED light bars around, and they appeared to sparkle in slow motion across the screen thanks to the Notch effect. One aspect that the team learnt with Notch is that such effects had to be added after the filming and audio were synced together, as a small lag develops as the filter works on the live content, which otherwise would leave the two out of sync.

Because of the size and scale of Melodifestivalen, there is an increased chance for this production to push the boundaries, try out new equipment, and be at the forefront of modern live event production.

Advice For Other Delegations

Nowadays Sweden is on its own for holding a multi-week tour around numerous venues in the nation to select their Eurovision entry. Norway previously held a tour across different towns across the country from 2006 to 2013. Finnish broadcaster Yle has noted that despite UMK’s popularity, licensing issues restrict the public broadcaster in public-private partnerships like SVT, making the tour viable. Yes Estonia and Lithuania change the location of their shows from Semi Finals to Final, but a full tour rotating around towns across the country they are not.

Tobias Åberg outlines one word as key for any broadcaster wanting to follow the Melodifestivalen model. Prepare. “We copy the routine, more or less like Eurovision. All the routines help to stop things getting out of control, with dry rehearsals, viewing room sessions, in-ear rehearsals.”

“Sweden has succeeded with a bigger crowd and more viewers, and I hope more countries also are able to have a show like this one.”

The Swedish Melodifestivalen has for a long while been at the forefront of not just music but also for its production and its reach across the Swedish nation. There are no signs of that stopping any time soon.