In the aftermath of the 2023 Eurovision Song Contest, many are reflecting on why their favourite entries did not end up performing as well on the night as they had hoped. 2023 was a year that several people described as having the strongest overall Big Five submissions, yet four of the five on the right-hand side of the scoreboard, including the UK and Germany in 25th and 26th (last) place respectively.

In order to score points at the Song Contest, you need to come in the top ten of a country’s televote or jury vote. Loreen’s triumph in the jury vote wasn’t only accomplished through topping the jury vote in 15 countries; it was also accomplished through the fact that every single country’s jury awarded at least four points to Sweden. Second-placed Israel received no points from six different juries.

This has led to soul-searching about whether the UK’s 25th place may have been a result of near misses. Maybe several countries ranked Mae Muller somewhere in the low teens, with her final score not reflecting her position in juries’ and televoters’ rankings.

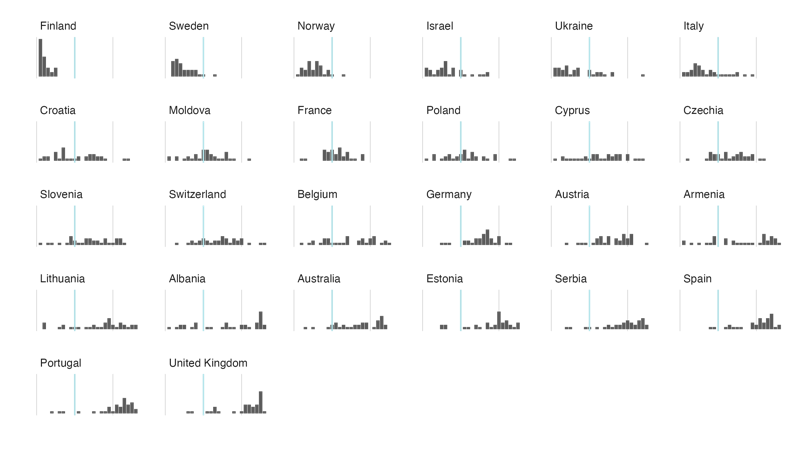

Distribution Of Votes

Our first graph shows the number of televoters awarding different numbers of points to different countries. A spike on the left-hand side means lots of first places; a relatively flat graph means an even distribution of rankings from 1 to 25 (or 1 to 26 for those televotes whose countries’ entries didn’t qualify for the Grand Final).

Eurovision 2023: Televote Distribution (Mark Taylor)

The UK has the worst overall average in these rankings. Not only did they receive ten last-place rankings, but another sixteen national televotes also put them in position 21 or lower. Whatever we might think of the song, this isn’t a set of results that looks mid-table. In contrast, Albania received nine last-place rankings but was in ten countries’ top tens, topping the table in Switzerland.

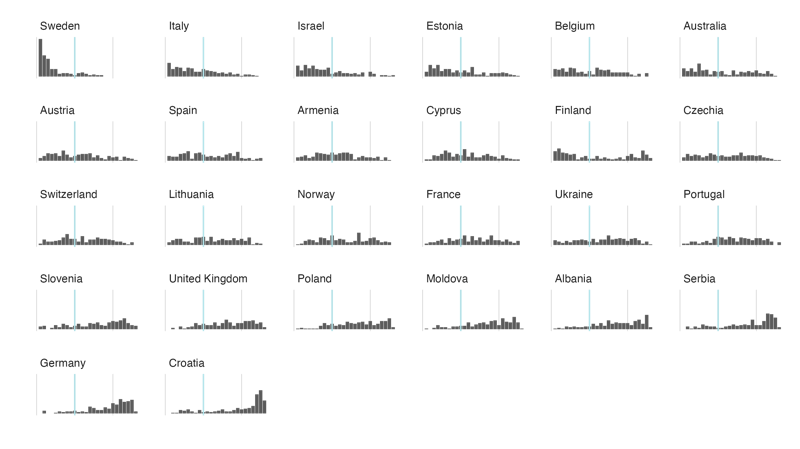

Among the juries, it’s a different story.

Eurovision 2023: Jury Distribution (Mark Taylor)

This graph shows the ranking for each song among every single juror. I Wrote A Song may have only received a few jury points, but several jurors had the song in the middle of the pack. This may not have meant points, but it’s also not the drubbing that people in the UK may have felt it was.

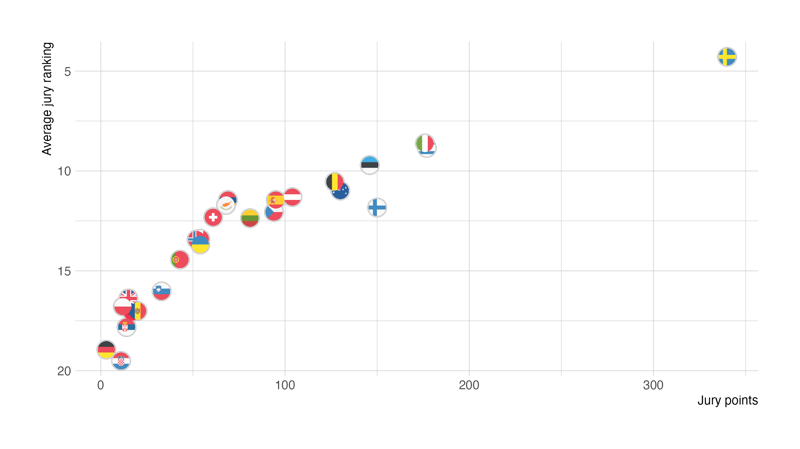

Comparing Rankings With Points Scored

We can see the effect of the points system by comparing how countries did in points with how they did in their overall jury rankings.

Eurovision 2023: Jury Points vs Ranking (Mark Taylor)

Among jurors, the relationship seems pretty close overall, but there are a few interesting areas to highlight. Finland (150) may have just edged Estonia (146) on jury points, but Estonia was fully two places ahead Finland in the average rankings: 9.7 and 11.8 respectively.

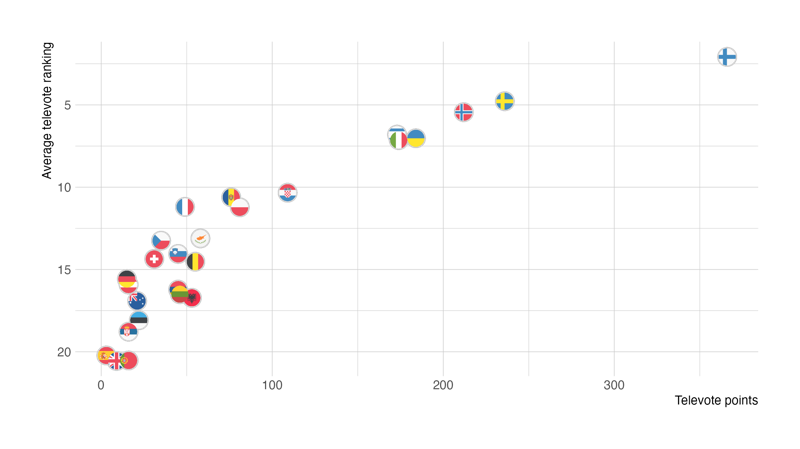

This is even more pronounced for the televote.

Eurovision 2023: Televote Points vs Ranking (Mark Taylor)

Six countries scored more than 170 points, meaning that, for everyone else, small differences in rankings could lead to big differences in points. On average, Germany did far better among televoters than Portugal, with an average position of 15.6 compared with 20.5. But the system means an act receives no points whether they came eleventh or 26th. This means that, despite an average gulf of five ranking positions, Portugal actually edged out Germany among televoters by a single point.

Finally…

What does this mean for the countries that were disappointed this year? One conclusion would be to send an entry that’s more divisive. An entry that everyone likes but nobody loves is likely to disappear into the middle of a country’s rankings, and that means no points. Then again, nobody would describe Lord of the Lost as a warm, fuzzy, and low-risk entry.

Maybe Germany and the UK had the right idea. It may not have paid off this time, but if they keep taking risks, they could be getting the high scores they need to win the competition.

Great analysis, great article.

thanks!