The morning of Saturday May 8th was one of those rare occasions where sunshine, actual warm sunshine, broke out across the skies of Stockholm. Following what has been one of the coldest springs in recent memory, I took the chance to get out into the back garden, just in reach of the wifi, and logged onto my latest venture into the Eurovision press bubble.

Like the rest of the ESC Insight team, we have access to the online press centre for this year’s Contest. This means that for me, and for 1000 other people accredited with online access, we are all able to follow the action from Rotterdam from the comfort and quiet of our own homes, and away from the cacophony of a press centre.

It’s a beautifully swish set up that the team from Let’s Get Digital, based in Groningen in the Netherlands, have created. On logging in and completing your profile one lands at a home screen where you can easily find the schedule of the day, contact details for the delegations and news updates from the EBU all in one place. The ease of navigation across the platform is a joy.

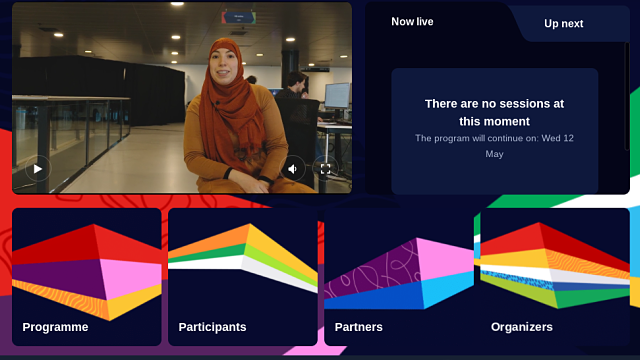

Samya Hafsaoui presenting the daily news update in the lobby of the online press centre

However, to find out about how it works as a platform I spoke to the person behind its implementation. Let me introduce to you Babet Verstappen, the Head of Communications at the Eurovision Song Contest this year, who squeezed in an interview with me just before guiding government ministers around the press centre in Rotterdam.

Making The Digital Experience Feel Live

From the very beginning the team behind the online press centre said they were looking to recreate the live event feel. The aim, according to the Eurovision Song Contest Head of Communications Babel Verstappen, is to “make sure the press want to stay on the platform for two weeks so they don’t miss a minute of what is happening at the Rotterdam Ahoy.” Even though this has been an aim from the start, actually seeing it burst into life as the online press centre launched was a huge surprise.

“Everybody jumped online and everybody was so happy to see each other and to be back at Eurovision. From Day 1 on the Saturday (the online media) were very active not only in rehearsals but also in the press conferences.

I feel now there are less people in the room, but online they are more active.”

The high levels of activity and engagement online has resulted in changes even in the first day of operations. The first few meet and greets were focused on the members of the press in the Rotterdam Ahoy. By the afternoon though, the decision was made to switch focus to the online chat, allowing “more than 70 percent” of the questions come from the journalists in the online chat.

Online chat itself is a double-edged sword, and all that interactivity comes at the cost of embedding a constant stream of chatter that is often overly opinionated and confrontational – to the point when one must question if it makes the online press centre a safe working environment with its lack of moderation and reporting tools. To this point, the EBU Communications Team have felt compelled to request that “when watching rehearsals, all journalists respect the values of the Eurovision Song Contest and treat artists with respect.”

The demand for streaming, and the online press centre in general, has been higher than expected. The follow-on issues from this is that many journalists have noted issues with buffering, due to the high quality the videos are streamed at. To cope with this, meet and greet videos and news updates are now stored outside on a separate platform, and viewers can now alter the quality on the web stream to try and allow for a smooth viewing experience.

At one point in these early days there were 550 journalists simultaneously using the platform. Combined with those already in Rotterdam, for these early days of rehearsals that is considerably more journalists than would be attending a conventional press centre at this point of time in a normal year, despite no increase in the number of accreditations. The rationale for this is that many journalists, fan community or otherwise, can’t commit two solid weeks to be located in the host city.

Victoria from Bulgaria performing on the Eurovision stage in rehearsal (Photo: Andres Putting, EBU)

This situation prompted Babet to think that this year’s pandemic influenced decision actually creates an environment that should live on beyond 2022.

“In the first few days it works to have this hybrid solution, where you can jump on to have this platform available before some of the press even arrive into the host city, as some arrive just for the show weeks for example. Now you can already start from home from the very first day. Now I’m not from the EBU but I feel for the future this has to stay, in the next few years people will wonder how they can join the meet and greet and follow rehearsals, wanting to engage like they do today.”

And I think I would agree with that. The sudden shift into working online throughout the last year means that the world of 2022 will not and should not replicate the world of 2019, and an online press centre is a part of that solution.

So, how can it get even better?

A Global Audience For A Global Contest

From Sweden, Slovenia and Switzerland journalists have been logging on to this online platform to follow what has been happening at the Rotterdam Ahoy live. But the Eurovision of today goes beyond those countries on Central Eurovision Summer Time trying to access the information. The obvious example is Australia, with journalists down under needing to stay up until the early hours of the morning in order to keep up with the rehearsals from the other side of the world.

This demand to be viewing the press centre as live was a surprise to many. It was a surprise to myself, having worked at Melodifestivalen in February and March where all features were kept on demand after viewing. Babet explained that the decision to only allow for people to watch rehearsals live was made “together with the EBU” and that the reasoning was to reduce the chance of rehearsals leaking into the public (which did happen during Melodifestivalen this year). Reducing this risk, Babet explains, would help make the delegations “feel comfortable” with the transition to the online platform.

Yet this decision is not without criticism on the other side. The American Alesia Michelle is one of the Eurovision world’s most well known commentators, but has chosen this year to stay stateside and use the online press centre to help cover the contest. The decision to stream rehearsals as live came as a shock and affected her ability to balance Eurovision alongside the rest of her life.

“When I found out that the rehearsals weren’t going to be available on demand that definitely shifted things for me. After covering Melodifestivalen from the States this year I assumed that process would be duplicated. As a single mother and full-time digital communications professional I didn’t know if I’d be able to make it work. Luckily with some supportive friends and boss – that knows how much I love the Eurovision Song Contest – I am hopping into these feet and living on CET time for the next few days.”

One of the great benefits of the digital revolution is the removal of the need to not just physically be in the same space, but also the need to consume information at the same time. The solution at the Eurovision Song Contest 2021 only addresses one of those pieces of the pie. There are technical solutions that can reduce the chance of leaking (individual watermarks comes to mind as an obvious one), and the benefit is that we have a system that is accessible not just continent wise but globally. In a world where big companies realise working at home is going to have to be a part of the future, whenever and wherever that may be, the Eurovision Song Contest must also follow suit.

Investing In The Future

The idea for the digital press centre began, Babet confirmed, during the preparations for the four alternative scenarios that the EBU put forward for this year’s show, depending on the nature of the pandemic. That process began last summer and eventually led to the wide shortlist of alternatives that resulted in the platform we are using today. The aim then was to find a solution that would fit the Eurovision Song Contest 2021, to survive the pandemic situation, and no more. Custom building a feature like this was an option considered, but, for just two weeks of usage, would be terribly expensive.

Remember that the Eurovision Village is also moving online for this year

Should this be a feature forevermore, then that could well be an option to do centrally and carry through from year to year. This would allow for more integration with the EBU’s own work – such as in-house photography, video to be incorporated into one universal space. There are two terrible situations that we could end up with – one, the idea that we just revert to the Eurovision press centre of the past and two, the reinvention of the online press centre wheel as we travel from host broadcaster to host broadcaster. And it’s not that we should be thinking of this long term as a hybrid model anyway, with a press centre online and physical, but an integrated press centre hub that is an asset to both those physically inside and outside.

And despite some of my criticisms above, this is fully the type of platform that we should have at the Song Contest and a great starting point for the future of the digital space at the Song Contest. According to Babet, delegations were “very positive”, and especially at the ability to follow, engage and interact from the first day. This can spread a delegation’s workload so that they don’t have all the media attention over the last week, and it is so much easier and inviting to interact with delegations through this platform, rather than scouring the media handbook for the list of Head of Press contacts, that the system design encourages for far more press/journalist interaction than you would otherwise have. I noted while writing this piece how the Israeli Head of Press popped into the chat room to say they were going to do some interviews in the afternoon, message me if you are interested.

And that was the point when I realised that this wasn’t, and shouldn’t be, an article about just improving our own media experience. We tell the stories, but the artists create the stories of the Song Contest. The online press centre allows for more opportunity to see what they deliver on stage, learn about their background and ultimately interact in a whole variety of ways. It makes the storytelling about the Song Contest easier, and has been a great edition to the behind-the-scenes of this year’s Contest for all.

See you all online again in 2022, wherever in the world the artists remain.