There’s been no big announcement, no flashy animation uploaded to the YouTube channel. Instead news of this voting change stumbled across eagle-eyed fans glancing through the FAQs on the official website.

The full text is as follows:

Eurovision.tv FAQ screencap

The voting system is still 50/50, with the juries voting first one by one followed by the combined televotes. However since this voting system was introduced in 2016 the televotes were read out in order from who had the lowest televotes first, and then up to the highest support from the public.

The change here means the country who scored last from the juries will know their televote score first. It doesn’t matter if that their televote score was 0, 20 or 400 points.

Still confused? Thankfully the ‘ESC Luxembourg‘ channel produced a example of how this presentation would look using this system for the 2018 voting with a mix of audio editing and scoreboard CGI:

There are some key advantages to this. Firstly the system is much simpler for the production to follow. The broadcast team know which country is getting points next, so it’s easy to find a camera to get in the face of the artist for an immediate reaction. Usually we miss out on the reactions from the lower order because they all get read out too quickly. However the production crew will have more time after the jury scores are available to plan their camerawork attack. This applies also to the script, which can be quickly updated and used on the autocue.

The second major benefit of this system is that it’s far more simple for the person at home to understand. If you are reading this article you probably know your Eurovision voting patterns to an encyclopedic level, and you’ve more than likely been brought up on a formula of Melodifestivalen since your fandom began. That’s not the same for the general public, who just see numbers bouncing around a screen in utter chaos and confusion. Starting from the bottom means you know which country is next and you know where to look on the screen. Just having one thing less to focus on makes this an improvement.

It also maximises the chance of that dramatic ending. Of the three editions since the 2016 voting change, it is the latter that ended on the biggest nailbiter of them all. Not just that it was Russia vs Ukraine, but also because we were waiting to see if the televote winner ’had enough points’ to leapfrog the leader.

With this system we will be asking that fateful question once more – will they have enough points? The only difference here is that rather than seeing if the televote winner can overhaul the leader, we are asking the same question about the jury winner. This does mean though we are guaranteed a head-to-head climax – what every producer wants to achieve.

This all being said, I strongly believe this presentation approach is the wrong approach. In making it simple and focusing towards that entertaining finish, we lose part of the joy that is the Eurovision Song Contest and what it stands for.

Positive Voting

One of the finest aspects of the Eurovision Song Contest is that it doesn’t get bogged down with negativity. We cut the camera to celebrate who received the 12 points from each jury, and the image we see is of flag-waving jubilation. It’s only the supernerds who trawl through the raw data to find out which Armenian juror didn’t place Azerbaijan last – these scores are rightly kept out of public’s immediate view.

With the televotes in recent years we rattle through all of the lower scores to focus in on the top ten. Then we pause, go through one at a time and take the voting of the top ten with the televote. Each one is happy that they scored well with the public, even if they don’t win, and there is a general feel good effect.

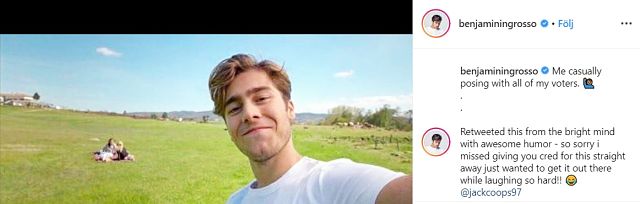

If we instead go in order of jury scores then we could have some real clangers. Last year’s show is great example of this. Much has been made of Benjamin Ingrosso’s low televote score, and I’m sure the ripples of laughter still echo around the boat in Stockholm where I watched last years final.

Benjamin Ingrosso / Instagram

However what we remember most in the aftermath is Benji’s social media reaction, and we remember him for being a good sport. Imagine the furore of being in the final three with a chance to win the contest, only for hopes to be dashed and ending up falling significantly short. It’s highly unlikely the immediate Swedish reaction would have been as humorous and courteous in the moment, it would be a big shock. The Eurovision Song Contest should not be about broadcasting such cruel situations across the continent’s TV screens.

Juries Are Not Like Televotes

Another premise of this system is that it makes it more exciting because you would expect the winners of the jury vote to be scoring high with the televote as well. We remember the Benjamin Ingrosso and Michal Szpak anomolies, but because they are exceptions to the norm we expect.

Running some maths on the last three Eurovision editions, I compare the correlation between the jury vote and the televote scores using Spearman’s Rank Coefficient. In the statistics presented below, a number of +1 means a perfectly positive correlation (i.e. they are the same as each other), 0 means there is no relationship and -1 means the relationship is perfectly negative (i.e. a high jury vote means a low televote).

By using the rank coefficient I take the placings of each country from 1-26 in each list (jury points and televotes) rather than the score they received. This is more relevant as the placing the song receives is what is key for the purposes of production.

| Year | Coefficient (to 2 decimal places) |

| 2016 | +0.08 |

| 2017 | +0.07 |

| 2018 | +0.24 |

| Average | +0.13 |

An average coefficient of +0.13 is, at best, only a very weak correlation. Jury votes therefore have little in common with televotes. I would argue that using the jury votes as the order to announce televotes is therefore a bad idea, as they are equally as likely to disagree with each other as they are to agree. It means that, like in 2018, you may have a script encouraginging suspense and drama but realistically the voting results are anything but.

Who Gets The Screentime?

As we get closer and closer to the end of the show, the voting should get more dramatic as we reach the final stages. This means that those still in contention are going to get far more airtime in those final few minutes. Unless their televote score was large enough to overhaul everybody, chances are a televote favourite lower down the pack has already been knocked out of contention. Out of contention means out of the competition, and means out of sight for the viewers at home.

This is the wrong way round – the people are home should see their champions in the spotlight when it is their points being announced, not the choices of 5 people in a stuffy back office of a TV station. The public have already suffered the jury favourites being ahead throughout a 40-plus country satellite link to gain that advantage. The televote should, if anything, be more exaggerated to celebrate those the public really love.

There is a secondary issue in giving more focus to those ahead with the jury. Our friends over at ESCNation pubilshed a great visual image of which countries do better with juries or better with televotes over the past week. There is a clear difference from east to west.

The western countries almost uniformly score higher with juries and the televote is stronger for those from the east. What our new presentation means is that the eastern countries lose out far more in terms of airtime, and the western countries linger ’in with a chance’ for more of the show. In recent years we’ve had Sweden, Denmark, Austria, Sweden, Ukraine, Portugal and finally Israel winning the Song Contest. We don’t need to do any more to make the West appear better than they are – they are already dominating.

There Must Be Another Way

I fully accept that the new presentation does make the voting easier to follow, and does make for a dramatic reveal of the winner, and that a change that does these aspects is worth pursuing. However I have explained above why I believe this system could actually make a voting presentation that is less engaging to the viewer – with less popular acts highlighted and climaxes to the voting sequence that offer little genuine suspense. It’s also a negative for many acts and delegations, who may be embarrassed by a low televote and laughing crowd… only for that also to be broadcast to the entire world.

There is an alternative way that can tackle both problems.

My model would work that we run the jury votes as we do now, and the televotes are still accumulated from each country. There is no difference. However instead of reading out the lowest score from the televote, I propose we start by revealing which country it was that finished 26th overall. And then 25th… And then 24th…

Take Lisbon 2018. We would reveal that Portugal was last place overall, but quickly move on to 25th, 24th, 23rd. We don’t linger on any of these final placings. It is easier to follow because the countries now align in order from the bottom right corner of the screen.

Sweden finished 7th overall. When we get to 7th place there is still shock that Sweden is announced, but there is still success – 7th is a perfectly respectable result. The Swedish team would shrug their shoulders and smile at the camera.

Austria finished 3rd overall. Cesar would smile, bow to the audience, and then we get stuck into the real business.

Who won the 2018 Eurovision Song Contest? There are only two left – Israel or Cyprus?

The winner is…..

For me this is a better system than what the EBU have now put forward. Successful acts get the airtime they deserve. Nobody in the final rundown is put on camera to look like a loser. We get a genuinely exciting ending between two songs that most likely got support from both juries and televotes. We create stories about success, not failure.

It is great that the EBU are trying to make the presenation of scores in the Eurovision Song Contest more exciting. However the ways we do that should promote celebration, not increase the risk for embarrassment.

Hi Ben,

I read your proposal in great detail. In the end I think the more generic TV viewers at home don’t care so much. But looking into the matter more deeply, I think the system used between 2013 and 2015, where both the 5-headed juries and the televote aggregate had to give their full TOP 26 result, was the best.

I think it’s best if we wipe out those hefty differences between the televote and the jury-vote altogether. Like with Sweden 2018 (high jury vote, low televote) or Denmark 2018 (high televote, low jury vote). Televoters at home and audiences alike don’t have the time for loud boo-ing then. And it also softly ‘unites’ the fans of televote entries (prone to certain….visual memes) and jury entries (prone to incredibly choreography, incredible hit-worthy songs, incredible vocals) too. Also, whereas the televoters only have to vote for their favourites, jurors really need to do their uttermost best. And their TOP 26 rankings matter more in the 2013-2015 system.

The biggest problem in this case, indeed is, the entertainment factor. You never get it exciting. Hence we have the current system.

But what about playing more with the order of when the spokespersons give the points from their nations? If I’m correct, that’s still being decided to create some suspense for certain countries near the end of the 100% jury voting. And it was also done in the pre 2013-era (50%/50%). An example is Italy 2011, who fairly late were awarded lots of points. Hence they came 2nd. I think this can be done if you use the 2013/2015-system, and split the votes from all 41 nations in two. Then you would get something like this:

Part 1 of the voting:

–> first 21 nations gathered together

–> these nations are chosen upon a certain outcome (countries A, B and C are doing well with Part 1, but less good in Part 2)

–> these countries get to present all their results with spokespersons

–> these points will be announced completely, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10 and finally 12 points

–> because only 21 nations announce, there’s also time to announce them in French

Part 2 of the voting:

–> last 20 nations gathered together

–> these nations are chosen upon another outcome (countries D, E, and F are doing better in Part 2, but less good in Part 1)

–> these countries will be presented by the presenters, and put straight away on the scoreboard from lowest 26th place to 1st place

–> spokespersons as backups, because beforehand you don’t know which of them will announce

–> here also announcement in both French and English could apply

Advantages:

–> Voting will be shorter

–> Harks back to some Eurovision traditions

–> People have no direct clue about which entries will be loved by either televoters or jurors and vice versa

–> Music will stay as diverse as ever, but every entry gets the attention it deserves in the 50%jury/50%televote aggregate

Disadvantages:

–> At this stage this is perhaps way too complicated, especially for the show’s producers

–> Perhaps it’s a bit too much about cheating the viewer into excitement

I suspect the current format of 50/50 split is here to stay, the TV is fantastic. 2012 to 2015 had some voting sequences that were tiresome to watch, even when we made the voting order more exciting. Competitively speaking I had huge issue with songs that could score nil points from a country because of a low jury ranking, so we would need to accommodate that (the new algorithm could arguably be a solution to that).

I am not completely sold on the new way of presenting the televote results.

It has the potential of being very exciting or we will know the winner before the end of the voting sequence. Like all new things we will have to wait and see how this works.

Your suggestion,Ben, sound more promising and should be at least considered by the EBU. If you have any connections there, where you can submit your suggestion, by all means😁

Regarding Ben’s profile, what exactly makes Chisinau, Ventspils or Tirana “bizarre”? Talk about western-centric patronisation…