Voting In Melodifestivalen Finals

Melodifestivalen’s voting system is one that is very comfortable to the modern Eurovision fan, after all it is the model that the Eurovision Song Contest uses nowadays.

It is a split of juries and televotes, with the number of points split between the two 50/50. Each of the juries presents their votes first, and the tension is kept high while we wait for the televotes to appear at the end of the broadcast.

A slight nuance between Melodifestivalen and the Eurovision Song Contest is that voting is open not just during the performances, but lines are also open for five minutes after the jury results have been revealed. Perfect for your last minute tactical vote.

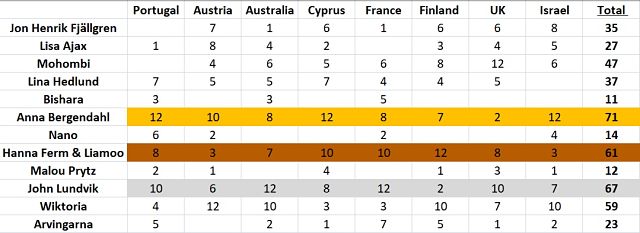

Each of those juries will vote just like in the Eurovision Song Contest. 12 points to their favourite, followed by 10, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1. This means only two songs will get zero points from each jury.

The televote has been in recent years a proportional system, the percentage of votes received was translated into a score so both juries and televoters gave our equal number of points. One major disadvantage of this system was that it led to very equal televote scores between the competing songs. This is especially true in Sweden as by using SVT’s app with free votes many viewers vote for more than one song. Nano won the 2017 public vote, but wasn’t close enough to challenge for victory then.

However that app this year has had a radical makeover, and that makeover has transformed the voting system. The people of Sweden will no longer be subordinate to those international juries – they will have the power to decide.

Power To The People

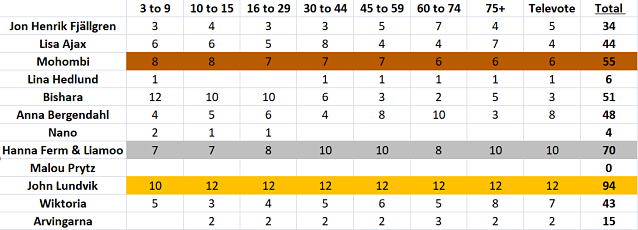

Melodifestivalen’s new app has the same interface as before, with viewers being able to cast up to 5 free votes per competiting song. What is different for 2019 is that on signing into the app you have to give your age. This puts you into one of seven different groups – with the youngest being from 3 to 9 years old and the oldest 75 and over. Members of each group cast their votes, but rather than a proportional result each group votes 12, 10, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1. There is also a phone vote option, which is worth the same as one of those seven juries.

According to SVT, if this system was in place for last year’s competition it would have resulted in the same 8 songs qualifying directly to the Friends Arena final. This means that we can assume the difference in song taste is marginal at best between those different age categories. A song scoring high points from the 3 to 9 year old block is likely to score high not just from the 10 to 15 year old group, but each and every group.

In 2018, the public voting spread from a low of 37 to a high of 67. This year I can predict a more ruthless public voting – perhaps multiple songs will have only single figures from the public while at the top end of the leaderboard many songs may comfortably score more than last year’s winner. The maximum number of points a song can score from the public voting is 96 (12’s from all eight groups), and a uniform favourite could hit the mark.

The voting sequence will feel more like that of older Melodifestivalen’s from before the App first existed in 2015. While Melodifestivalen Final voting has been mathematically 50/50 since the 6 week tour started in 2002, App voting gave significantly more than 50% of the power to the juries. Now the power of the 50/50 is almost certainly back in the hands of the televote. Miraculous escapes to victory, such as Malena Ernman’s comeback victory in 2009, are now back in the realms of possibility.

International Juries From Australia to the UK

To make it 50/50 voting – the eight public voting groups are matched up with eight international juries. They come from the following countries for 2019:

- Portugal, Austria, Australia, Cyprus, France, Finland, UK, Israel

- Many commentators have discussed how this spread of countries is very Western in background. This is a comment Christer Björkman, competition producer for Melodifestivalen, is well aware of, saying he hopes ’it will not make much impact.’

The issue is that the number of international juries has decreased from 11 to 8, so a geographical spread is harder to achieve. Personally, I don’t consider this to be a huge concern. Previous studies on jury groups has concluded it is who you watch the show with, rather than where you are from, which is a bigger factor in the overall result.

However, what is a concern in terms of finding the best quality winner is that we only have eight juries this year for Melodifestivalen. Jury voting is usually is far more random than it is uniform – which is not a surprise when juries are only made of the opinions of a handful of people compared to millions of Swedes. Christer Björkman is aware of this – and has described the increased statistical risk as ’scary’.

Putting both the juries and public voting together means there is an increased sense of the unknown when it comes to predicting this year’s Melodifestivalen winner. We have an incredibly strong odds-on favourite currently in John Lundvik, but with a jury vote and televote potentially harder to predict there are certainly no foregone conclusions at this point.

Trying To Model The Voting Sequence

To end this article, I’ve had some fun to try and create some ’fake’ voting using proxies to simulate both the jury voting and televoting.

First the jury voting. What I have done is found points from different fan forums across the internet. I have taken different 1-12’s from different websites, with different fans voting on them, and used that to create a jury score for that country. By searching for English language websites I hope to get an international opinion to the songs. I also used SVT’s Twitter poll as part of these pretend results – they had filtered for an international fan opinion and this gave Wiktoria the top ranking.

Model of the Melodifestivalen 2019 Jury Vote using data from international fan forums

For the public voting, I have combined different proxies in different amounts to create a suitable score. For younger audiences I have used YouTube views or Instagram followers, and as the voting group gets older I have used data from sources such as newspaper polls, Spotify streams or iTunes.

This would give a public vote as follows.

Model made by using different proxies to predict the public vote in Melodifestivalen 2019

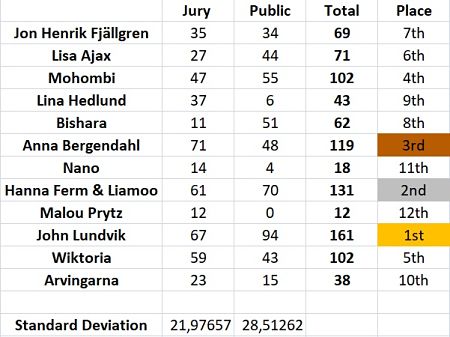

The combined result of this is therefore the jury result plus the public vote.

The result of this mock voting combining the jury and public vote scores

Now, you are probably looking at these numbers and wondering how X could be high and Y could be low – and I agree. However the numbers here look like what the Melodifestivalen vote will appear as – it is a great example for how spread the final result may be.

I included the standard deviation here to show just how spread the data is. The larger standard deviation for the public vote shows how the public 50% now is more powerful than the jury 50%. There is more chance of a climatic finish to Melodifestivalen 2019 than recent previous editions.

What is important for ESC Insight readers is to be aware of what the results will look like because of the voting system. For a start there is zero chance of a record score on Saturday night – the low number of juries means simply less points are on the table. However the chance of seeing a song come close to a full televote from all ages would make big headlines. That’s a headline Frans couldn’t achieve in 2016 – he scored 50% more votes than 2nd place that year but so many app votes were cast viewers such a whopping televote still only took 14.4% of the total. Frans’ huge landslide barely made a dent on the scoreboard. A landslide on Saturday night could catapult an artist all the way up the leaderboard.

With this voting system we are going to get unpredictability, we are going to see drama, and we are going to see a song popular across all of the Swedish population winning the trophy. Let the best song win.