“We have experienced some problems with the online voting, but we are checking.”

With those words from the EBU’s Gert Kark, the popular story of the Junior Eurovision Song Contest 2017 was set. No matter the challenging nature of the Russian song, the return of Portugal after ten years, or the very first key-change in any Australian Eurovision entry, Tbilisi will forever be ‘the Contest where online voting failed.’

How Can It Be A Success If It Failed?

I’m not going to minimise the impact of the online voting issues, that’s a hefty weight on one side of the scales. But I want to look at the other side and propose that the EBU made the correct decision to implement an online voting system, that it was beneficial to Junior Eurovision, and it was perfectly in keeping with the ideals and aims of the Eurovision Song Contest brand.

That said, it probably needs at least another year of testing before it can even be considered for the Adult Contest.

Where Did We Start From

It’s worth looking at the conditions that the EBU faced in gathering a public vote for 2017’s Junior Eurovision Song Contest. Two countries were broadcasting the show on time delay (Ireland and Australia, although if you wanted to get up at oh-my-god-its-early Down Under then you could watch the clean feed being relayed on ABC.me) so the traditional phone/text window was not possible. Even if it was used by the rest of the entrants, the lower viewing figures in some countries meant that getting enough valid votes to protect the integrity of the results by passing the various thresholds was challenging at best. Junior Eurovision 2016’s experiment with three juries and no public component to the vote left a bad taste… this is a show that is meant to be inclusive. That includes being inclusive of those watching in coutnries which did not have an entry.

Given those limitations a move to the internet for an online vote was the best answer.

The challenge comes in deciding how you identify the voters and audit for multiple vote casting (either by accident, by experimentation, or with more forethought). This is a challenge for any online voting system. Some broadcasters use a social media login (typically via Facebook) to identify voters. Other ask for an account to be created with the broadcaster and users must sign in (The BBC has such as system to cast your votes on Strictly Come Dancing). These are more secure but demand more time and patience from the voter.

Although the EBU has access to its own social network (myeurovision.tv), and the Eurovision events have significant presence on Facebook, the voting system instead used other methods of tracking so that “only one vote was counted from a single device.” We understand that the time to process votes through this security system held up the vote during the show.

The High Wire Nature Of Live Broadcasting

Nothing ever works one hundred percent on a live show. Both Lisa-Jayne, Tony Currie, and I know where the mistakes, the flaws, the changed scripts, and missed opportunities were in our live radio broadcast of the show. No doubt the TV production of Junior Eurovision has a similar list. Voting is one of them.

But you practice for failure and you make sure you have many options. In the case of the online voting, the EBU could still count the votes that were successfully cast during the show. Depending on the number of connected sessions to the voting server compared to the votes cast you can have a good idea how many are uncounted. Given the number of votes cast its likely these will be in roughly the same proportions.

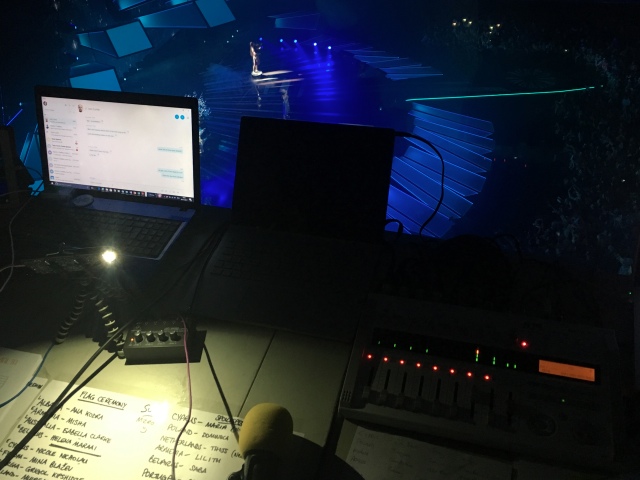

You never want a blank monitor during a broadcast, but you practice in case it happens (image: Ewan Spence)

Live broadcasts always have fallback positions for pretty much every system. They are discussed in advance because you ”plan for failure’. For example, with the vote starting on Friday and closing on Sunday as the show started there was a set of online votes already locked in and presumably printed out to be used if required. If the online voting system had went down completely during the show it would have been embarrassing but there would still have been a valid vote that had been running for 46 hours.

You hope not to use them, but they are there. The key phrase in Tbilisi was not ‘there was a problem’ but ‘we have a valid vote’.

What Did Work?

Engagement worked.

Rather than a fifteen minute window of voting, the 2017 Junior Eurovision Song Contest saw the delegations, performers, and the fans all start pushing hard for votes and recognition from Friday 6pm CET before the Contest. That offered two days of increased social media presence, a call to action to every fan of the Contest, and alerting the fanbase of every performer that they were taking to the international stage.

Junior Eurovision became a longer experience, even though the show was, curiously, one of the shortest Song Contests of the last decade. It remains to be seen just how much of an impact this had on viewing figures – although they are down would they have been down more without two days of online push – but there was an increase in awareness. That awareness was worldwide, which meant that voting and participation as not restricted to the sixteen countries in the Contest, but everyone who wanted to watch online (assuming the show wasn’t geo-blocked in their country for complicated musical licensing reasons).

Polina Bogusevich and the Junior Eurovision trophy (EBU/Thomas Hanses)

Media consumption habits are changing. Everyone tuning in at once for a single program is no longer the norm. While competitive events such as the Eurovision Song Contest remain as appointment viewing, opening up the voting window allowed people to consume part of the show on demand and according to their own schedule.

That does diminish the impact of the live show, as previously discussed here on ESC Insight, but is that loss balanced out against the online gains?

Eurovision is not just a four-hour show in May (or a two-hour show in November). The contest within the contest that is Eurovision already relies heavily on PR and marketing, there’s a need to have an efficient ‘get the vote out’ system, and its about leveraging a delegations limited resources to create the most buzz online to capture attention as the voting starts. This year’s online voting at Junior Eurovision has simply codified the long game into the rule book. It’s clear that some delegations had worked through the game theory of winning Junior Eurovision more than others.

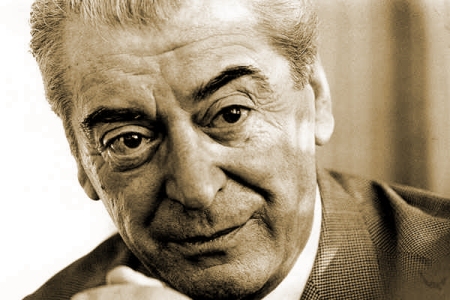

Marcel Bezençon Would Be Proud

One of the guiding principles given to the Eurovision Song Contest from its father, Marcel Bezençon, was its use as a test-bed of new technology (alongside bringing countries closer together and the ability to share cultures). There’s no doubt that this year’s Junior Eurovision accomplished all three, but the use of online voting is a clear nod towards using the Contest as a platform to test new technology for the benefit of all of the EBU’s members.

Marcel Bezençon

You have to remember that computer code is hard to write, and testing it before deployment is even harder. There was clearly an issue with part of the online voting system during Junior Eurovision 2017. Let’s acknowledge that a mistake was made, but let’s also acknowledge that the introduction of online voting addressed many concerns of Junior Eurovision fans, has given the EBU and its broadcasting members a significant amount of data regarding engagement and participation, and reminds everyone that the Junior Eurovision Song Contest sits at the cutting edge of live television.

I’d call that a success.

You know there is a big problem in predicting the number of enteries to this site.Also we are encountring problems in purchasing the tickets for the ESC events. I think due to poor evaluation in number of people who wants to vote or to buy the tickets for the events so the website of the Junioreurovision or the various official tuckets their websites crashed. I am sure there are some experts who can evaluate the volume of people who want to vote or to buy tickets and the moment the prediction of it will be coirrect so there won’t be any crashes of the various official websites

Of course they’re going to say ‘we have a valid result’. It’s a classic case of organisational backside covering. Large numbers of viewers being denied the chance to vote on the day can’t be called a success.

That said, the concept of online voting clearly has its merits but, especially if it is to be introduced at Adult Eurovision, a number of issues need to be addressed including minimising voting ‘fraud’, stopping people voting for the country they reside in and, if allowing votes in advance of the televised performance, preventing ESC from turning into the Eurovision Best Funded PR Machine Contest.

Eurojock, just to be clear, we don’t know how many viewers could not cast a vote so ‘large numbers’ is putting words in the mouth. And there was a valid result according to the voting rules (the mythical ‘Green Book’) of the Song Contest. That vote did not include votes which could not be validated.

But as you rightly say, there are clear merits in using online to gauge opinion.

Hi guys,

again thanks for your covergae of all things ESC – I do totally believe you know where the flaws/mistakes/missed opportunities are in a live show. I’m not sure the Jr ESC organizers do though – in my experience, the bigger an organization, the biggere its lack of self-awareness!

Also I love the nick Eurojock. POlease eitrher let me steal it or marry me!

4P