Making A City Come Together

The City of Stockholm laid out great and grand plans to host Eurovision 2016. The iconic Globen Arena, as well as its neighbouring venues, provided perfect logistics for organising a show on the scale of the modern Song Contest. The arena was supplemented by two equally stunning locations in the heart of the city.

Eurovision fans of a certain ilk will be familiar with the EuroClub/Fan Cafe complex, the temporary structure with a near 5,000 capacity by the Palace. Within staggering distance was Eurovision Village in the city centre square Kungsträdgården, complete with live concerts and sponsor stalls galore for the general public. Extra events, such as Eurovision swim discos and samba football, were organised outside in the city suburbs.

The organised events were well attended, with Globen approaching capacity for all three live shows, and the Grand Final rapidly selling out as per tradition. EuroClub was able to offer over 2,000 accreditations to OGAE members meaning it was bouncing every night during the second week. Eurovision Village basked in glorious sunshine and tons of tourists and Stockholmers ventured under the cherry blossom.

However there has been a spiralling cost attached to all this. In September 2015 Stockholm City guaranteed a contribution of 60 million SEK (€7 million) to bring the Eurovision Song Contest to the capital city. This rose in the official budget, published October 2015, to 85 million SEK. Just prior to the start of rehearsals, Stockholm City projected a final cost was 100 million SEK. Post-Contest this was revised upwards to a final cost of 102 million SEK. This cost is over three times the 28 million SEK directly spent by Malmö City and the Skåne Region in 2013. Some of this money has been spent on infrastructure investment, including Globen and the surrounding area getting a well deserved spring clean, and for the singing tunnels which will haunt the capital until the New Year.

This is a considerable financial commitment for a local government to put towards hosting any major event, and it is an amount that needs to have achieved demonstratable success.

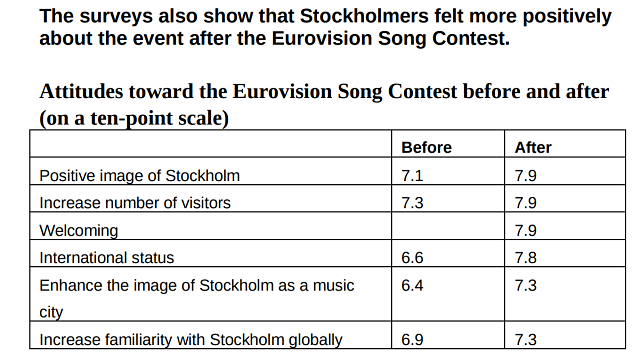

On September 21st Stockholm City sent out a press release proudly boasting 263 million SEK of revenue coming into the city (an average of over 2,000 SEK per visitor per day, nearly €210). Local events had 9′ out of 10′ approval rates, and the support for hosting the Song Contest in Stockholm rose from 58 percent at the start of the year to 70 percent post-Contest. 9 out of 10 visitors to Stockholm perceived the city as ‘open and welcoming’, 8 out of 10 gave Stockholm the top rating for a host city and 7 out of 10 ticket buyers would be interested in returning to Stockholm in the future. On those barometers, as Ann-Charlotte Jönsson, Communications Strategist for Stockholm City replied, “the result passed all our high expectations.”

Stockholm City managed to raise the city’s reputation with local residents through hosting the 2016 Eurovision Song Contest

There is some caution to be had with this everything-was-fabulous rhetoric. The revenue value from hosting is actually slightly less than Vienna projected the previous year and in all honesty it’s likely many ticket holding fans would be returning to Stockholm because of Melodifestivalen anyway regardless of their experience. While the Eurovision experience may appear to have been one big success, let’s review each part of Stockholm’s offering in closer detail.

Eurovision’s Most Spectacular EuroClub?

There is no doubting the statement Stockholm City and SVT wanted to make in establishing the EuroClub for this year, arguably the boldest practical example of 2016’s ‘Come Together’ motto. From the outset of planning, bringing all fan and celebratory activities under one roof was the mission. To build such an impressive temporary structure on the waterfront of the Royal Palace showed an incredible gesture and evidence that Stockholm was using the Eurovision Song Contest as a platform to impress. Stockholm proved it can co-ordinate incredible events and will continue to do so, EuroPride 2018 will come to Sweden after winning the bid in September 2015.

Fans were ecstatically happy with the venue choice. The location was wonderful and the fact so many fans have got access to the official EuroClub has kept fans together, and allowed them the chance to party with delegations and press. Some of the crowd reactions this concoction produced made for truly magical moments.

That being said the venue also at times felt very much like what it ultimately was… a tent without Mary Berry (…too soon?).

With Stockholm City’s costs escalating throughout the year, the price for the extra ‘OGAE’ accreditations for fans was eventually set at 500 SEK. Still relatively affordable for two weeks access to the premier venue in town, it was double the cost of Vienna’s €29 Euro Fan Cafe. In total a revenue of over 1 million SEK (just over €100,000) was raised through the fans, as well as the extra drinks income from some very thirsty individuals over the two weeks.

One would assume that the ambitious project would require more revenue from fans, but even so this increase was steep. Furthermore remember that there was only one venue being created this year with EuroClub sharing the building, rather than having to finance two different locations. Other than the venue and the booking of a handful of artists and hosts there is little evidence of what the money has gone towards other than the pockets of Stockholm City.

Most of the events on the schedule have been co-ordinated by hard-working volunteers from Melodifestivalklubben (OGAE Sweden) and OGAE International. All daytime events such as artist meet and greets, quizzes and the Fan Media activities were co-ordinated on a voluntary basis. The Swedish fan club utilised its own 150,000 SEK (€16,000) budget which made up prize contributions for quizzes and for inviting artists to attend, mainly for the OGAE night on Wednesday. Neither of those organisations saw any of the income from accreditations in their budgets, and yet have been essential to make sure Fan Cafe became more than just a late night disco adventure it may otherwise have been. We all know how important the fan community is to Eurovision, but here they have thanklessly put their hands in their pockets to make it possible. We should all thank the Swedish club tremendously for their generosity.

While the activities have trundled along well on the whole, the Fan Cafe experience had been fraught with issues throughout the two weeks, with some events being cancelled and moved at relatively short notice.

An important example is with rehearsal showing, which was a big feature mentioned in January by Mayor of Stockholm Karin Wenngård. While rehearsals were shown in Fan Cafe and garnered a cult following, this was only applicable to times when Fan Cafe would be open. Despite requests Fan Cafe wouldn’t open to match the rehearsal schedules. In the end both German rehearsals were shown at early times when Euro Fan Cafe was closed. It was a clear example of policy that squeezed the budget down further rather than providing the promised fan services.

Water was ‘not tested’ at the venue for the first few days, meaning staff couldn’t offer free water, a Swedish standard practice, without it being at visitors’ own risk from the toilet sinks. In the scorching weather the selection of cakes from the cafe were untouched at a time when everybody was craving for ice cream and BBQ’s. The venue itself was given the full scale security treatment that put off many casual visitors from popping inside and seeing what the fuss was about. A necessary precaution, one can argue, but not enough thought went into encouraging everyday locals and tourists from making it a daytime venture, one of Stockholm City’s objectives.

Delegations could lounge around on the sofa beds above the EuroClub main floor (Photo: Lina Åhman, SVT)

This year was that there are so many more people attending the Fan Cafe and the whole set-up was incredibly more integrated in the actual Contest than ever before. So much is a huge plus. But with this influx a greater need of professionalism is needed to make the events flow as smoothly as they can. To leave enthusiastic, hard-working, dedicated amateurs to the scheduling tasks left too many blank spaces in the shell Stockholm City provided. If such a big venue does translate into another Swedishism of 21st century Eurovision, it needs more support centrally about filling it with the extra trappings that make it ‘Eurovision’.

A Village In The Heart Of Stockholm

Eurovision Village was another beautifully arranged and iconic venue in Kungsträdgården, a stone’s throw across the water from EuroClub. The creation of a second stage area, covered roof and the City Skyliner made the place a natural hive of activity.

Certainly in terms of looking impressive there was little to complain about with the way Eurovision Village was presented this year. The walkways over Kungsträdgården’s water in particular were a cool touch. The inclusion of a diverse program of schools, local acts and tributes was on the whole appropriate, but so would more couplings to the Song Contest throughout the festivities. One can question the magician warm up to the Grand Final when some Melfest starlet would have got the crowd properly buzzing. The music around the village was more often than not away from a Song Contest playlist and the merchandise stalls didn’t come along with all the insignia and officialness it deserves.

Stockholm City appeared to have made this all work on their own, and there wasn’t any obvious nod to the official activities at the venue.

Another mention here could be some of the co-ordination with delegations. Part of the Eurovision Village highlights are to get some of this year’s acts performing for the general population. Fewer Eurovision songs were performed on stage in Kungsträdgården than previous years. Busy schedules and tight deadlines are one reason why, but also there is a whole communication train from the host city through SVT to delegations that has to exist, and many of these conversations happened too late this year. It little wonder the schedules for EuroClub, Fan Cafe and Eurovision Village were delayed until just three days Eurovision fortnight officially begun. ‘Time and money’ were cited by Ann-Charlotte Jönsson as reasons for the delays.

Even so, more information was being added in during the Eurovision fortnight, with no definitive schedule correctly including all of the events happening. Stockholm City put fifty of their communication officers in the press centre to deal with the media. However what was missing was one of them to be the definitive central body for co-ordinating each venue’s activities and distributing that information. The team from Stockholm City social media accounts tried to keep up with advertising the events, but this team weren’t given accreditations to follow anything inside EuroClub or anything in the arena. These knowledge gaps meant they missed out on capturing and sharing some of the best Eurovision moments that happened inside those iconic locations and meant fans didn’t get the clearest picture of what was going on when.

An Entire City That Came Together

Stockholm City wanted to make sure even the suburbs within this capital got a chance to be a part of the action. Five different locations got involved in its ‘In Your Neighbourhood’ initiative, offering creative activities like improvised comedy, quizzes and samba football. Not the most Eurovision of activities I agree, but for this the most important thing was using Eurovision as the excuse to come together and celebrate. Having visited the event in Husby just before the Grand Final, there seemed to be a missed opportunity to utilise the full connections of the Eurovision circus. For example in Vienna a great invention was to utilise the Stand-In rehearsal artists for Eurovision Village. Those students were not utilised this year after appearing on the Globen stage, which could have provided a value-for-money and very relevant connection for Stockholmers. Much more than the tasty but albeit out-of-place samosas I munched on.

My prize for winning the (factually inaccurate) Eurovision quiz should not have been a bright orange T-shirt with ‘Husby’ on the chest, but some memorabilia to show that the event was a part of this Eurovision bubble. Instead this was an separate side attraction thoughtlessly covered in Come Together posters.

Victorious I was (Photo: Alison Wren)

There was not enough Eurovision going out into the suburbs to do brand Eurovision justice. In the same vein, there was not enough interaction from the suburbs going in and enjoying the spectacle. I attended three shows in Globen, Monday night’s Jury Semi Final, Tuesday’s Family Show and Thursday’s Semi Final live broadcast. As you would expect, Globen was bouncing for the Thursday showing and there was an electric atmosphere around the entire arena. On Monday for the Jury Show, the first glimpse for many fans of the actual arena, there were certainly pockets of atmosphere but large swathes of the expensive seats lay empty. Certainly videos from that night, used as preview performances for the Big 5, don’t give the impression of a packed out spectacle – it felt like the rehearsal it was.

Tuesday’s Family Show was even more sad. Most of the floor was barren, much to the delight of toddlers with plenty of space for running around, and there were far more seats unfilled than taken. One fortnight running up to the show tickets were offered for free to local schools for this show, as well as the Jury Finals on Monday and Wednesday. That’s how I came in on the Tuesday, with 40 students who were already arranged to perform at Eurovision Village that afternoon. This offer though came far too late for any respectable educational establishment to turn around. We were offered up to 500 tickets, a staggering amount, but couldn’t turn the logistics around in time for that.

It was a wonderful gesture to offer those extra tickets to us and they were greatly appreciated by students who had, quote, ‘the best day ever’. However it was such a shame that this process was not a planned event way in advance. Local schools should have been invited in to fill Globen as a priority months before. Forget about trying to sell Family Final shows with a 15:00 start time for over €40 a piece, make sure the place is bouncing with people who will remember their time for long to come and take away the most incredible memories. That would have been a definitive Come Together gesture and could make thousands more Song Contest fans for life.

Stockholm knew it would sell out the Grand Final in seconds, and had prepared for it well by offering Tele2 Arena as by all accounts a well-prepared alternative, and an idea to pass on for future years. However the lust for midweek shows is always, no matter where, going to be lower. They need to be utilised as a way to bring new people in, especially young people and those from disadvantaged backgrounds, as a way to inspire a whole generation. Stockholm missed out on spreading that Eurovision love as far as it possibly could.

Stockholm’s Missing Legacy

For the City of Stockholm, the 100 million SEK, ever-escalating budget, for hosting the Eurovision Song Contest has made many Eurovision fans happy, but has left little direct legacy to the city. EuroClub was torn down the morning after, with the 2016 host city now lumbered with an excess of IKEA furniture stored somewhere in town. The singing tunnels probably annoy most residents by now too. However the statistics paint a successful story that perhaps prove to local residents again that Stockholm is capable of hosting world class events in the future.

Sweden’s Minister for Culture has offered expert help to Ukraine’s counterpart to help organise next year, and certainly Stockholm has proved itself to be an excellent events organiser. There is no doubt that the Stockholm Eurovision Song Contest was a pinnacle and an organisational highlight built up from a strong vision and creative solutions. Perhaps one beauty of hosting Eurovision will be to share more of that resource around the continent in the future. Ann-Charlotte Jönsson spoke highly in particular of the support Stockholm received from both Malmö and Vienna in the organisation of this year’s festivities. The same team who organised EuroClub and Eurovision Village in 2016 have already been to Kyiv to start that handover process again.

From a fan perspective, most Eurovision fans have been delighted with the EuroClub and Fan Cafe more for what it was, rather than its day-to-day organisation. The fact everybody could dance the night away together was the biggest win and something any host city must seriously consider in the future. It feels very much this factor meant the teething issues of an enormous tent were overlooked by many.

In conclusion there appears to be far less image building on show like Vienna last year, where a city was desperate to use Eurovision’s leverage to show itself as a more modern and liberal city. Stockholm’s approach has been calm, more ‘lågom’ as the Swedes would put it. Stockholm has shown it can deliver a beautiful Song Contest and the trappings around that, and that core is likely to be remembered positively for years to come.

However any finger of blame would be unfair to point solely on Stockholm’s shoulders for any missed opportunities, because the city can be proud of its achievements. What was clear this year was the lack of continuity that comes from a new city building a home for the Song Contest year after year. The Contest is probably the biggest worldwide event any city organises with such a short timeline ahead to prepare. Whichever city hosts has to make up things as they go along with little support from the European Broadcasting Union. It is after all brand Eurovision that has missed out most from the shortcomings, not the City of Stockholm.

Brand Eurovision And Spreading The Love

Now yes, the EBU shouldn’t be overly concerned with dressing a city in regalia, but lots of what happens in the host venue and beyond has a measureable impact. Eurovision has been growing rapidly in the last two decades and the extra deliverables can’t just be left to chance. That goes far beyond specifying how many hotel rooms they want to block out in May too. The EBU should actively require a set standard for host cities to deliver the goods that has more stringent requirements than today. Ann-Charlotte Jönsson said that ‘there is no manual on how to host’ the Contest. Maybe it is time for that to exist.

Take accreditation for example, did any eagle-eyed person spot that the thousands of OGAE accreditations were not included on the list of accreditations on the backside of the plastic? These may have been approved by the EBU, but were never written into the system despite the all-in-one idea coming from Stockholm City way back in the depths of 2015. It’s indicative of the hands-off approach shown to the activities outside of the arena bubble, and even though some host cities may have stumbled across failure (sorry Copenhagen), it’s a miracle no PR disaster hit a city during Eurovision week itself.

Furthermore the karaoke package at EuroClub was run by Stockholm City’s own team, who did so without any Eurovision playlists to refer back to. These should be gifted to each city as part of a handover set to make use of. The co-ordination of delegations within the city events should have EBU support that goes above and beyond passing over contact details of Head of Delegations but actually as a central problem-solving information point. The event that is hosting modern Eurovision now requires central strategic focus.

Eurovision Song Contests of the future are going to attract growing numbers of fans and media and that isn’t looking like stopping soon. As such, there needs to be a higher set standard for the events and facilities laid on by a host city in combination with the TV spectacle. The Eurovision Song Contest might want to take a closer look at the scale of operation performed at the European Football Championships this summer in France. There on page 16 for the world to see, is a split of responsibilities for host cities and UEFA for co-ordinating each of the Fan Zones, the equivalent of the Eurovision Village. There’s a lot to learn from how this works.

Now is the time for a step change in the city organisation. Host cities, even those with the confidence of Stockholm, need central assistance to make their big ideas reality. They also need the support from a core hospitality team who can deliver a world-class party that truly brings a city together, bringing the Contest out into every limit of the city and bringing the city residents into the Contest itself. An excuse for a party and some cake shouldn’t suffice any longer. Basic requirements for hosting a EuroClub, a Fan Cafe, a Eurovision Village, an Opening Ceremony, a Red Carpet Event and all of these little moments of wonder in the two weeks, need to be stepped up and supported more centrally. Currently there is a happy-go-lucky and make-it-up-as-you-go-along-ism to these extra tidbits to the Eurovision circus, and as a result brand Eurovision misses out on selling itself to its full potential.

The key takeaway is this. Stockholm has produced one brilliant show, an iconic EuroClub and deserves applause for the extra effort and vision it brought to the Song Contest. However the Contest is now too big and too much for a city alone in a fifty week turn-around. While Stockholm can be satisfied with its role the final few percent missed were those that would make the Contest shine as well. With Eurovision heading to Kyiv help and assistance are going to be essential, but they should be stepped up regardless. To continue the growth of Eurovision taking over a host city effectively the EBU need to step up and make hospitality a core part of their support package. Eurovision will get bigger, but it needs to get better as well.