Why Did The Orchestra Ever Leave?

The disappearance of the orchestra from the 1999 Eurovision Song Contest was easy to miss for a casual fan. The Song Contest in the 1990s evolved with grander stage shows, more camera tricks and high energy lighting effects that the visuals of brass solos and rousing strings were pushed further away from the visual identity of the Contest.

Officially, the EBU list three reasons why the orchestra left when it did. One was purely financial, that keeping an orchestra on site for all the preparation, rehearsals and live shows was something that could easily be cut from the expanding budget. The second was the increasing ‘limitations’ an orchestra gave musically. More music was being composed electronically, and trying to use a backing track alongside orchestral accompaniment was a frustration for many performers. It meant that artists and songwriters could finally get ‘absolute freedom’ and control over how their songs sounded, without the risks of conductors and soloists interpreting the black and white marks slightly differently.

As we approached the new millennium, Eurovision had once again found itself as a commercial platform for artists. The risk of Eurovision’s three minutes being somehow different and therefore ‘wrong’ to listeners at home was something to avoid. By the time the orchestra did leave, it had already been on death watch for many years.

Vienna, the spiritual home of classical music, hosted Eurovision last year, and naturally there were murmurings that if the orchestra could come back, it would be in 2015. After all, the EBU broadcasts the traditional Vienna Philharmonic’s New Year Concert each year across the globe. Relationships were already established. The Philharmonic did appear in the Grand Final, but only in supporting of the opening act. Publicly at least, there was never even a sniff of suggestion the orchestra would return. Seeing a modern Eurovision with the glitz, glamour and glorification of show, the traditional orchestra does feel a generation (if not two) away from the current Eurovision trends.

Orchestras In The Modern Eurovision Era

A desire for the orchestra is not merely a old-fashioned wish. Eurovision’s birth was influenced by Italy’s Sanremo, the stallion of the world’s song contests. Now in it’s sixty-sixth year, the orchestra is still going strong and is an immovable force from that contest’s image. It ditched the orchestra in the mid 1980s, only for it to swiftly return a few years later. For this great beast of Italian culture the grandeur created by the orchestra was simply impossible to replicate.

Yes, ‘Grande Amore’ was orchestral heaven in its production and structure, but still generated Il Volo commercial success locally and abroad. That classical sound still has a relevancy today. One does wonder if their runaway televote victory would have been complemented by a top jury score if the Vienna Philharmonic had crescendoed alongside the three gentlemen of Sanremo.

Across the Adriatic to Albania, Festivali i Këngës attempts to balance a blend of cultures old and new. During my time at the most recent FiK, artists speaking to me were mixed on the orchestra. Some complained of it taking away the sound they want to create on stage, and others loving the passion and energy only the live feeling can ever create. However the orchestra is a part of Albania’s tradition just as much if not as much as in Italy, and for better or worse it seems unlikely to change.

What was particularly interesting in the 2015 National Final season was the addition of another country using the orchestra. Norway did not have a tradition to uphold, but the eleven acts could choose whether or not to use the 54-piece Norwegian Radio Orchestra to provide backing. The choice here seems to be one of celebration, with the show being twenty years old, and taking place thirty years after Norway’s first two victories, which were both heavily orchestral themselves. The orchestra was used mainly it seemed for NRK’s show simply to ‘stand out’, but it also helped in contest as the top four were all songs fully using the orchestra.

There is little doubt that eventual Melodi Grand Prix winner ‘A Monster Like Me’ would have utilised an orchestra in Vienna if the option was there. Composer and performer Kjetil Mørland has stated how he couldn’t afford to pay the orchestra to record his backing track for Eurovision, doing the hard graft himself.

With the removal of the orchestra, Eurovision lost one of its great equalisers. We are now seeing an increasing technological race between those countries who can afford the top-notch modern productions that deliver the results, whilst the poorer half of Europe struggles to compete to match the rich tones and comforting soundscapes viewers expect. An orchestra, however traditional, can guarantee a high quality of sound that many new artists and smaller broadcasters can never justify paying for themselves.

Ironically a Eurovision orchestra might be expensive, but it would be likely the smaller nations of Europe who would want to put the extra into the pot to give them a better chance at the carrot of success.

Lessons From Albania: The Inner Workings Of Orchestras

While present at Festivali i Këngës I spoke to Elton Deda, the Artistic Director for the competition. This role involves managing the 60-strong orchestra, but also creating many of the arrangements for the competing acts and guest artists. We spoke about how much time it takes to put together such a show from his perspective… after all the orchestra did not come to each live show unprepared.

For each of the singers performing, they had rehearsal times on the days of their Semi Finals as well as the days prior. In total they got between six and eight attempts to perform their song together with the orchestra. This number is comparable to the amount of rehearsals Eurovision Song Contest acts get on the big stage before the jury performances. However the orchestra alone also perform the song before meeting the artist another half a dozen times. The orchestra runs through each song at least one dozen times before playing to the public.

Albania’s National Final orchestra, stage right (Photo: Ben Robertson)

In addition to this, there are also the interval acts for each show which were extensive. Not just for rehearsals, but also for arranging and writing the sheet music. Elton said the time varies; it can be really quick with some songs, but occasionally a few minutes of music can take ‘four to five days to match it all together’. It’s intense craftsmanship at play.

If Stockholm were to bring in an orchestra for the 2016 Eurovision Song Contest there would be 43 three-minute songs to prepare for. On this rehearsal schedule they would need to play for at least thirty hours before performing to the public. However they would likely be needed for far more time to hang around as artists enter and exit the stage and faff with camera angles. If each song used the orchestra today you would easily need the orchestra on the ground for one month to prepare, a wage bill easy to see as uncomfortably large and easily avoidable.

It’s also easy to spot that although Festivali i Këngës has increased the production value in recent years, it lags behind other National Finals for delivering impact. One feature of a live orchestra is that timings are live, and sometimes song tempo might be conducted just a beat faster or slower. That makes it far harder to prepare creative backdrops and lighting effects to match the music, and when watching the show up close you did notice the lighting effects lag behind when switching from verse to chorus and so on. This difference with pre-recorded backing tracks is of course reduced to zero and enhances the all-too-important visuals.

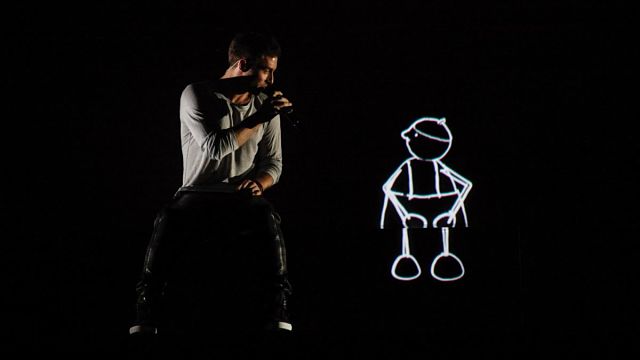

We all know how important the visual is to modern Eurovision (Photo: Thomas Hanses/EBU)

That loss is matched by a relic of Eurovisions from old, with the orchestra standing just to the side of the artists through each song. As the artists and songwriters are announced also tacked onto the list is the conductor, who received the polite applause with a equally respectful bow each time. I spoke to a few backstage, all repeating the same story to me. Only with the orchestra can they transmit the real, live emotions into the music. One conductor, who took to stage on Final night majestically dressed in a white three-piece suit, said music without an orchestra is ‘less beautiful, less interesting and less powerful.’

To conductors, the orchestra is priceless. How they manipulate the sounds around them from the country’s best singers must be amazing, and it certainly added to the atmosphere in the Pallati i Kongreseve. Yet much of that raw passion that is live music is lost in transmission to viewers at home. Can the costs ever be justified when the main impact is only on the thousands, rather than the millions?

If Not A Full Orchestra, Just A Little Bit Of Live Music?

I wanted to come away from Albania full of energy to passionately advocate that Eurovision needs that live buzz only an orchestra can bring, but no. The orchestra did add emotion, but not enough to be something Eurovision needs to crave. It would be a lovely thing for a broadcaster to include if they are passionate about it, and I would hope the EBU would support and encourage, but not a staple to bring in year-on-year and certainly not a requirement that all songs need to use.

That said, one off-camera moment seconds during Festivali i Kenges provided my eureka moment on this delicate balance. Between song 6 and song 7 of the show’s second Semi Final, on walked the operatic singer Genc Tukici. Walking out with him is a trumpet player, standing just behind his right shoulder, especially brought onto stage to play a solo. During the short postcard a couple of crew scurried around the trumpeter, attach a microphone, and off they run. He’s playing live, and it took seconds to set up before anybody at home noticed.

While bringing an orchestra might be unwieldy and costly, a few extra technical staff to hook up microphones, a guitar or two, or a few key instruments should be easily doable. It’s a choice Sweden’s selection process Melodifestivalen has allowed in recent years, where acts can play one instrument live over the backing track. ‘Heroes’ co-composer Anton Malmberg Hård af Segerstad played guitar for Le Kid in 2011 for example, as well as the live saxophone in ‘We’re Still Kids’ from two years later.

It’s a risk to play live for all involved, but a technical challenge broadcasters should step up to. Instrument sound levels can be pre-set from rehearsals just like vocals are, and any risk of bum notes are in the hands of those braver artists on stage. Some acts would jump at that chance to play for real, rather than have to mime down the camera. If we can offer those experiences to the artists, we should. Imagine the energy created from a Lordi or maNga all hooked up to amps ready to go and genuinely blast out the arena…rather than just pretend. With producer-led running orders to make the show smoother, there is no reason a well-rehearsed band and technical team can not walk on, hook up the cables and away they go.

Also some artists might just find this easier and far more natural. Playing piano or guitar live and singing for some can actually be easier than miming the piano to focus on the singing. That slight disconnect with timings and feedback can be jarring and makes the artist less comfortable. I know, I’ve tried.

It’s easy to see how Raphael Gualazzi may have wanted the live music option (Photo: Alain Douit, EBU)

In conclusion, when I look at the modern Eurovision of today and I think if you would include the orchestra, it’s impossible to argue that it’s essential. It’s honestly hard to argue even being desirable from a TV perspective, but it is easy to see how some artists want that live feeling, and that doesn’t necessarily need 60 talented musicians wasting weeks of their life.

Live TV like the Eurovision Song Contest should take risks and should push boundaries, and the show production is no different. Live music may not always be the correct answer for each song, but for those where it is we should do all we can to make it possible. The more we can encourage the there-and-now feel, the more this Contest becomes not just TV entertainment but the pinnacle of song and music as well.

Some interesting points there, but you also miss out on some important additional factors.

With regards to the orchestra, you didn’t take into account each nation’s individual Union laws. Most European countries have their own version of the MU, and have very strict daily hour’s worked limits. Any member of an orchestra who works above and beyond those hours is entitled to either down tools when their time is up, or claim considerable rates of overtime, which escalate incrementally on an hour by hour basis. In the old days where the singers just turned up on the day and the players merely sight-read the songs, this might have been OK, but with the ever-longer rehearsal periods these days, the organisers would either have to pay incredible rates of OT, or hire at least two orchestras to double up the hours – both of which would increase the overall budget by huge percentage points.

The other major issue you address is that of live instruments. As somebody who has stage managed some pretty significant festivals, I can assure you that it’s not simply a matter of ‘plug in and play’. Not only would you need significant extra monitoring equipment for all members of a band, and seperate and bespoke levels for each, but a mere 45 second line check would not be sufficient for even the best soundman to accurately assess the mix, taking into account the difference in atmosphere in the hall with a full, live, active crowd, and any difference in outdoor weather conditions, or the simple act of a ego-driven guitarist turning this amp up to eleven.

A simple mic’d up wind instrument or single drum may just about escape any need for a full on pre-performance soundcheck, but anything more major than that would risk some seriously performance-damaging sound issues – which is something that you don’t really want when you only have three short minutes to impress a continent.

And when you consider that the bulk of your multi-million audience will neither notice, or especially care how the musical sounds are delivered to them as long as they enjoy the song, then it’s an awful lot of time, effort and expense to go to just to deliver some semblance of authenticity where it’s not especially required.

All this just goes to demonstrate that there’s a lot more behind a simple performance than you could ever possibly imagine!

Broadly agree with Roy in that the orchestra is a “nice to have” but not really worth the amount of complications it’d entail. I don’t think any of the big award shows (MTV Awards, VMAs etc) use orchestra for their pop performances. Also we only need to look at disasters like Greece 1991 to see why the risk-averse EBU have expressed little interest in reviving the format.

I do feel for performers like Tinkara Kovac in 2014, for whom playing their instrument onstage is central to their performing style. It was clear in her case that being forced to unconvincingly mime playing her flute made her very uncomfortable and probably affected her whole performance. I always cringe when I see the guitar players waving their hands in front of their instruments too.

much like any fanfic or ship, haveing an orchestra or live music is nice in theory but would not work in modern eurovision.

if there’s any thing i want to change from eurovision is the over emphasis of (large) stadiums. one, it’s expensive. two, some drunk ogae fans ruins the moment by singing (see conchita and sana for 2014) and three, pandering to the audiance does not matter. the tv public and the jury (who are watching the show on a tv) are the only people that matter to win votes.

let’s get back to the more ecomonical and comfy theater shows or a stage like 2013

All rubbish. Its very simple: A Kraoke show can never replace live music