Why Would An Ad Break Be A Problem?

For anybody reading this, I imagine you are all the hardcore Eurovision fans. Those that come the magical week in May are glued to the screen for every last drop of excitement. You turn up the volume, flash up Twitter, and soak it every drop of rehearsal footage. Quite likely you already know the songs receiving your votes, and have done for many weeks prior.

Yet we simultaneously bemoan and rejoice that most Eurovision fans are not like us. It’s a once-a-year spectacular to wonder in how dazzling or dour the rest of the continent is. And whoever catches their attention, be it the Moldovan mad hatters or the half naked French dancers, a vote will be pop their way. And these are the ‘fans’, beneath them in the hierarchy are millions of casual viewers. People who stick to the national broadcaster because frankly there’s nothing better on the other side. These people are not so committed to the lengthy four-hour extravaganza the modern Song Contest has become.

Come one hour in and for all but the die-hard the need to stretch their legs becomes overbearing. The kettle goes on, the fridge explored for goodies and a line snakes outside the toilet door. Within a couple of minutes we’re back, live, and the next act is ready to rumble. It looks the same on screen, but behind the camera lens many of the audience has disappeared from view.

This is what Eurovision fans dread about the advert breaks. After them, some of the audience may not be back watching, and therefore give you a far less chance of scoring points.

We want to see if this theory actually is played out in Eurovision voting, to try and detect if there is any difference with the advert break. Here comes the maths.

Starting In The Semi Finals

For our analysis we are looking back on Eurovision Song Contest Semi Finals and Grand Finals from the introduction of Semi Finals. While we could look at the absolute success rate of songs performed after an advert break, such information is secondary to obvious factors of song and performance quality. Just in this small sample we have songs like ‘Leija’, ‘Undo’ or ‘Sound of Silence’ coming after the interval. Some examples of big hitters in the final scoreboard regardless of advert breaks.

The qualification rate is equally dismissive of this as a significant problem. There is a 51.2% chance of qualifying if you have performed after an advert break compared to a 54.3% average since 2004. Any swing away from success caused by an advert break is likely to be only a fractional difference.

However in competitions that are close, could this difference offer the tiniest of swings against a front-runner? This is why we start in 2004. With the introduction of Semi Finals we are able to compare the like-for-like rankings of songs in two different shows, to see if the chances of success go up or go down.

This is still flawed data in many ways. Tt doesn’t take into account the fact that there are more countries competing on the Saturday night, and thus lots of countries would score nil points from countries that voted for them in a Semi Final. Since 2008 too that also means more countries are voting on the Saturday night performance. Plus other known impacts, such as running order bias, can also impact on this data.

Nevertheless we found ten songs since 2004 which performed after advert breaks in the Grand Final that did not in the Semi Finals. There were also 22 songs that did performed after the Semi Final advert breaks, qualified, then did not have that ‘misfortune’ for the Grand Final.

Downward Trends

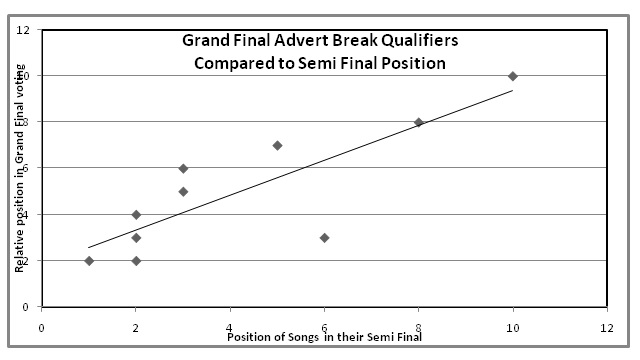

On those ten occasions songs performed after the Grand Final advert break the results suggest an overall downward trend in success. Six of the ten songs end up lower in rankings compared to their Semi Final position, and only one ‘Birds’ in 2013, relatively improving compared to the songs it qualified against on Tuesday night.

When using the line of best fit in the above graph, this suggests that for songs on the cusp of winning (placing in the first three in the Semi Final) there is an average drop of one position when compared to the other songs qualifying from their Semi Final.

However I would be cautious against suggesting this data was leading to a certain conclusion of a negative trend. Four of the six songs that we use here that did finish in the top three in their Semi Final had a markedly worse running order position in the Grand Final (‘Senhora Do Mar’ in 2008, drawn last in the Semi Final, is a good example). The above trend is far smaller for songs with a relatively similar running order position to their Semi Final placing, suggesting absolute running order is a more significant factor.

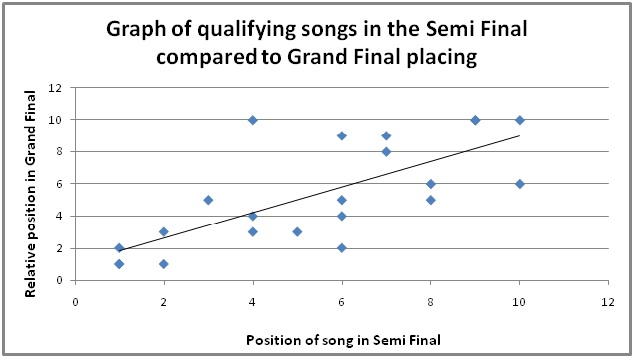

We can make the same comparison for songs that qualified in the Semi Final after an advert break, and see if they performed any differently in the Grand Final in the middle of the competition.

As one would expect there is less of a drag for the high placing positions, suggesting this way round is slightly more advantageous than before. However there are plenty of examples of improvers (‘Angel’ in 2011 moved from 6th in the Semi Final to 2nd) and losers (2008’s ‘Romanca’ dropping from 4th to 10th) to show plenty of other factors at play. It is somewhat noteworthy to mention that the last three winners of the Eurovision Song Contest performed after the advert break in the Semi Final (all in the second Semi Final as well).

If you take the total sum for all these song positions in the Semi Final, the total ranking combination is 119. In the Grand Final the number is 117, a tiny improvement in relative position but in reality insignificant over 22 different entrants.

The Conclusions Of The Advert Break Data

When looking through the qualifying percentages and the comparison graphs, it is possible to make a case for a small negative drag when performing after an advert break. However we would likely need many more years of data to make a stronger assertion. The trends measured are small and in many cases dominated by other factors.

The fact that any trend is small though is by itself a positive thing. It means that any impact from people not paying attention through the Song Contest is reduced. Perhaps those people who do disappear for long toilet breaks watching the show are not voting anyway, or perhaps they have already decided how to vote from preview videos, diaspora links…or from watching the Semi Final performances. This data here would help me lead to a conclusion that many fans watching Eurovision may have pre-determined their votes before Saturday night (and certainly proxy data like iTunes and YouTube views has been reasonably indicative of success previously).

Advert Breaks In The Producer-Led Era

Since 2013 the running order for Eurovision shows has been determined by the host broadcasters production team and then rubber stamped by the EBU. This means that no longer is the placing of songs after an advert break a random affair (and before you mention it, yes I know the advert break was moved in 2008 to account for Dima’s ice rink prop). The type of songs and performances that get placed around advert breaks is therefore now more predictable.

One of the reasons this may happen is to give the production team more time to set up for a technical show. Certainly that can be argued for Sweden in 2015, with ‘Heroes’ being a difficult song to set up due to the intricacy needed with the projection overlays. You can make similar arguments for other performances like ‘Rise Up’ in 2014 and ‘Slow Down’ in 2016. Just having an extra 30 seconds to arrange the stage here would make the production job a million times easier.

However by the Grand Final the production team have set up each show so many times they are supremely slick at any changeover that this appears to be less of a consideration. Since 2013 five songs have performed after Grand Final advert breaks; ‘Birds’, ‘Undo’, ‘One Last Breath’, ‘Sound of Silence’ and ‘Heartbeat’. All five are solos and offer performances that in their own way felt familiar with a dash of contempory flair.

That familiarity and normalism of each entry is key to why they are placed there. For those people coming back from their break at home, the theory of production is that they need a song and performance they can quickly engage with. Just like it is the current trend to start the show with an uptempo, fun, family number, it appears the returning song from the advert break is a performance that kick starts the competition once again.

What is slightly different for the 2017 Grand Final is that we have five breaks (some shorter, some full spots for commercials) in the running order. This is a clear production issue with the limitations of the Kyiv stage and getting big props like Robin’s treadmills and Lucie’s mirror petals off to the backstage prop area. The EBU’s release of a video showing the decision making of the running order shows that as much as flow of the show is an important consideration, so is the logistics of making the show work. Even with these issues classic up-tempo ‘back-to-reality’ songs appear after breaks, such as Moldova’s ‘Hey Mamma‘ and Azerbaijan’s ‘Skeletons‘.

Pause For The Conclusion

We have not found any significant data to suggest that being after an advert break is worse, and certainly the impact of a jury should negate some of this effect. However we’ve not completely disproven that a tiny impact could be felt. In competitions like 2016 where the margins were tight could we add advert breaks into the long list of reasons that resulted in Ukraine’s eventual 1st place. Did Australia miss out on a handful of televotes from a handful of people who just missed it, and did Latvia’s uplifting track settle the audience down ready for Jamala’s realism?

While I hope you all are critical of any impact an advert break has on the competitive side of Eurovision, the fact is that the perception of advert breaks being a factor will be very hard to shake. Songs after advert breaks are now deliberately placed to make the show either easier to produce or easier to watch at home. This sacrificial move may only have tiny impacts, but tiny impacts can change the world geopolitical world around us, as Kyiv has demonstrated all too clearly.