Over the summer there has been a renewed focus on Russia and its attitudes towards LGBT rights in the media. This issue is not confined to Russia, there are many more examples out there, some of which have impacted on the Eurovision Song Contest. ESC Insight’s Dr Paul Jordan looks at the issues and the impact large scale events can have.

The World Reacts To Russian Laws

In June 2013 the Russian Duma passed a bill banning the distribution of “propaganda of non-traditional sexual relations” and since then the country has rarely been out of the headlines. Pride marches are banned, and there have also been allegations that same sex couples displaying affection can be arrested. It seems that Russia, which decriminalised homosexuality in 1993, isn’t really following the all-encompassing sentiment that Dina Garipova expressed on the Eurovision stage back in May.

Such developments have unsurprisingly alarmed international human rights organisations who have voiced concern over what they see as growing authoritarianism coming from Vladimir Putin’s Kremlin. Recent raids of several non-governmental organisations (NGOs) across the country under the guise of “unannounced audits”, increasing media controls, heavily managed protests (read supressed) appear to confirm the concern from some observers that Russia is slipping into a dictatorship.

We’re just missing Robbie Williams, right? (Indrek Galetin, EBU)

These are interesting times for Russia and its rulers. Next year Sochi will host the Winter Olympics, an event which Putin himself worked hard to secure, evening speaking (phonetic) English in a bid to woo the international committee. Similarly to how the Eurovision Song Contest was viewed in 2009, such an event is an opportunity for resurgent Russia to flex its muscles on the world stage. Since the passing of arguably homophobic laws, there have been calls from around the world for the international Olympic community to boycott the games in Sochi, stating that attendance gives legitimacy to Putin and his cronies as statesmen.

To Boycott, Or Not?

Russia is of course one of the regular front-runners in Eurovision, qualifying for every final since the semis were introduced in 2004 and many fans have since debated about attending the contest should Russia win and host again. It is clear that these are deeply troubling times but are calls for boycotts of the Sochi games and a potential return of Eurovision to Russia justified? Will they achieve anything? Aren’t these laws merely a Russian version of the United Kingdom’s Section 28 legistlation?

Are these debates anything new?

Firstly, this editorial isn’t an attempt to justify the Russian anti-gay laws, which I find perplexing and deeply troubling as an out gay man myself, but I can’t help thinking that such calls for boycotts are potentially counter-productive.

Throughout its lengthy history Eurovision has acted as a platform for the politics of protest, no more so than over the past decade. The contests in 2009 (Moscow) and 2012 (Baku) were arguably some of the most politically charged in the history of Eurovision. It could be argued that the sparkle and spin of these events provide a façade of legitimacy to governments which do not uphold basic human rights, freedoms that so many of us take for granted. I’d argue the opposite. Such events put the hosts in the spotlight like never before.

The Spotlight Exposes Everything

Take Azerbaijan’s hosting of the 2012 Eurovision Song Contest in Baku. Azerbaijan, like Russia, used the contest as a platform for promoting itself on the world stage. However with this came serious political questions and brought debates to the foreground concerning human rights, freedom of the press, as well as the on-going territorial disputes with Armenia.

The Crystal Hall’s spotlights

Just weeks after Azerbaijan’s Eurovision victory, President Aliyev pardoned journalist Eynulla Fatullayev and 89 other prisoners. Fatullayev was imprisoned in 2007 for articles he wrote concerning the Nagorno-Karabakh war between Armenia and Azerbaijan as well as alleged possession of illegal drugs. Amnesty International described the charges as fabricated and stated that his imprisonment was related to his critical stance of government policies (Amnesty International 2011). Furthermore allegations of forced evictions during the construction of the venue, the Baku Crystal Hall, as well as denial of freedom of assembly in the run-up to the contest surfaced.

Further controversy came during the voting procedure in the contest itself when the German spokesperson, Anke Engelke, appeared to make reference to the political situation in Azerbaijan: “Tonight nobody could vote for their own country. But it is good to be able to vote. And it is good to have a choice. Good luck on your journey, Azerbaijan. Europe is watching you” (BBC TV, 2012). Perhaps the biggest irony is that it was a German company that built the Crystal Hall.

These striking counter narratives meant that the 2012 event was the most contentious in Eurovision history.

Is Attending Enough To Lend Legitimacy

By attending the event in 2012 was I therefore not a pawn in Aliyev’s PR machine? Wasn’t it just a case of drinking the free booze, partying and ignoring what was going on?

No.

I was fortunate to meet political activists who stood up to be counted and who were desperately pleased that the Contest was being held in Azerbaijan to shine a spotlight on the situation in the country. Those who called for boycotts of the 2012 Contest ignore this one crucial fact; so many people in Azerbaijan wanted Eurovision and its accompanying delegates to go to Baku.

The Maiden Tower, Baku

The issues facing Azeri society are serious and the actions of the government alarming, I’m sure those who were forced out of their houses weren’t too happy, but the fact is that without the Eurovision Song Contest these wider debates would not have featured in the mainstream global media to the extent that they did. By hosting the Song Contest, Azerbaijan was opened up to mainstream scrutiny for the first time since independence. It got people talking, and more importantly it got people mobilising through NGOs such as Sing for Democracy. Interestingly Eynulla Fatullayev is now said to be a pro-government human rights campaigner, attracting criticism from local and international activists. The plot thickens…

Situations do not change through ignoring them, they change from actions from within as well as outside. It is also worth remembering that the Eurovision Song Contest is in fact a competition between national broadcasters rather than countries per se. Of course some broadcasters are more independent from the state than others, which is in itself a different debate.

Not Quite A One Nation Europe

Homophobic attacks are said to be on the increase in Russia, and similar laws to the Russian one are being drafted in Ukraine and Moldova. Developments in Georgia in May show that Europe is not one, as the Malmö 2013 slogan claimed. The discourses in the mainstream western European press appear to paint Russia as the big bad bear trampling all over human rights and ignore the fact that we too in the United Kingdom have, at times, had a dubious record on the same issue (deporting two gay Iranian asylum seekers and telling them to be “discreet” to avoid reprisals when they returned) and it was only in 2009 that a gay man was murdered in the middle of Trafalgar Square, arguably one of the most diverse cities on the planet.

It’s the one-sided nature of the current debates which I find troubling. Why isn’t there international outcry over the fact that it’s actually illegal to be gay in over 70 countries across the world, a good number of which have our dear Queen Elizabeth II as Head of State? Then there are those who shout the loudest about gay rights and how homophobic Russia is and yet think nothing of going off to Dubai for the weekend.

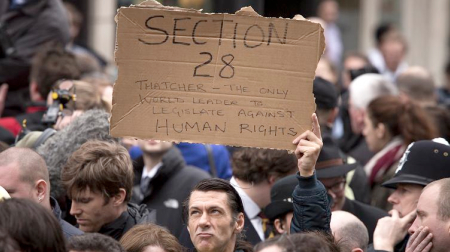

Section 28 Protestor (Unknown)

I deplore the new laws in Russia, inequality in all its forms should be challenged. On closer inspection though, they’re not too dissimilar to the laws introduced in the UK under Thatcher in the 1980s. Section 28 was repealed and the Conservative Party now repudiates too. The UK has changed, that took time and effort. Arguably homophobic laws still do remain on the UK statue books – take the blood donation ban which is flawed on so many levels. Interestingly, in Russia men who have sex with men are not banned from donating blood whilst in the UK they are.

The Personal Impact

On the surface, the situation in Russia looks bleak however gay friends of mine who live there tell a somewhat different story. Life goes on; yes things are worrying but never doubt the resilience of the human spirit. The gay scene in so many Russian towns and cities is vibrant. Russian gay brothers and sisters are negotiating their way through this, as the British did through Section 28. If they want our help then of course we should be there.

Developments in Russia are a reminder that the freedoms so many people take for granted can be taken away so easily. It’s telling though that the Russian situation and that of other countries sometimes doesn’t get a look-in at the various Pride festivals which have taken place this summer across the UK. The problem comes when “we” think we know best. As Milija Gluhovic argues, we “should remain wary of an uncritical acceptance of the language of freedom, including sexual freedom, considering the paradox that human rights and humanitarianism can be seen to operate as tools and strategies of contemporary imperialism” (Performing the New Europe, Gluhovic and Fricker 2013).

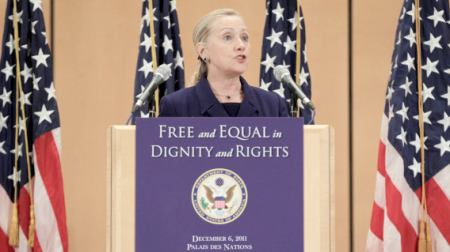

“It should never be a crime to be gay,” Hillary Clinton

This isn’t an attempt to gloss over what is a serious and developing situation, the point of this article to provoke some thought and debate. All too often we get stuck in our own bubbles, without thinking outside the box- I’m guilty of that too. Hilary Clinton was spot-on when she went on record to say that gay rights are human rights. She has also been spot-on (in my opinion) when she talks about gender and racial equality, these issues do not exist in isolation. Situations also change rapidly – look at the UK with Section 28, look at other EU members such as Estonia. Recently an article appeared in the mainstream Estonian tabloid, Õhtuleht, questioning the decision to send an openly gay athlete to Sochi. Although this could be dismissed as an opportunistic attack on Russia, the fact is that a national tabloid spoke out against homophobia. Times seem to be changing.

Potentially the situation in Russia might not be safe and Putin has already said protests will be banned whilst bizarrely the Russian authorities have provided assurances to the International Olympic Committee that gays and their supporters will be safe. What’s arguably even more perplexing is the Daily Mail’s stance on the entire Sochi debacle – criticising the Russian authorities, yet only a few weeks before carried articles concerning the “gay mafia”.

There Is No Simple Answer

It’s a truly interesting debate and one which I will continue to follow with great interest. I firmly believe that events like the Olympics, Eurovision, and athletics championships, are great causes for celebration, but with these events come responsibility. To us, the lay people, it’s a personal decision to visit countries and places which might be at odds with our values. Awareness is perhaps most important, it’s all too easy to see what we want to see, ignore what we want to ignore, and take for granted the basic freedoms and values that none of us were actually born with. The fact that we are free to have these debates makes me personally grateful since so many in our world are not.

Large-scale events afford countries the opportunity to shine, but they are also placed under a spotlight, as London was in 2012, which is a good thing. Let the Winter Olympics take place, attend and ask those serious and important questions, make the authorities accountable and even make them squirm! This slow burn approach is one of “normalisation”, to quote Michel Foucault, a complex process by which otherness might be eradicated. But then who is to say what is normal? It seems that Russia is just as perplexing twenty years on from the collapse of the USSR than it ever was. But that’s true of the world and indeed the Eurovision Song Contest!

Totally agree with your points about the one-sided nature about the debates (I’d call it hypocrisy actually). In fact, pretty much agree with everything that’s been said. Well thought out and written Dr E!

x

What an insightful and generously-perceived and written article. You’ve pointed out long-standing hypocrisies and outdated thinking that I had no idea still went on in countries that her Maj is still connected to. Your positive take on host nations having the spotlight on human rights issues pointed firmly at them is a point of view I hadn’t considered before either. Brilliantly written.

Russia or the Soviet Union has been persecuting (killing, deporting) minorities for decades (Jews, Balts, believers in God, politicals, etc, and now we want to exclude them from ESC? I believe this issue is only now on the radar because let’s face it, the majority of hardcore fans are gay men and somehow bashing or boycotting Russia makes them feel good about themselves.

A well written, well thought out article that I almost universally disagree with.

I support boycotting Russia, as I do with countries like UAE. Russia is not the worst, but It’s the one that everyone is talking about and we have to start somewhere.

I’m against boycotts – as a principe. And sometimes people think too much inside their own bubble 🙂