Introduction

If you have ever watched a rehearsal video from the Eurovision Song Contest or a National Final, you might have seen a box with a timer running and various numbers on screen.

That is CuePilot, and it has brought about some major changes to the look of our Song Contest.

What Is CuePilot?

CuePilot’s Eurovision debut was in 2013, and has been used in numerous National Finals. It lets Directors pre-program the camera work, allowing for more creative, advanced and appealing performances for those watching. The Director programs the shot list for each performance and synchronizes it with the other aspects of the performance, such as sound, lighting effects, pyrotechnics, and the video backdrops). This allows the visual show to be run ‘on automatic’. It reduces the potential for human error in a live show, which in turn allows for more advanced performances to be created with the help of quick cuts between cameras or the introduction of video-based special effects in a live performance.

The visual script is programmed into an online platform and shared with each of the camera operators who each get an individual script so they know when it is their turn to be live and what image they should be providing at that time. The usage of CuePilot enables the camera work of a performance to run multiple times under the same conditions, and helps delegations to alter and improve the visual look of the performances at the Song Contest.

Using CuePilot in Australia’s very first national selection, Eurovision: Australia Decides 2019.

CuePilot And Eurovision Rehearsals

During the rehearsal weeks of the Eurovision Song Contest, the journalists and bloggers in the press centre often try to analyze if the camera work helps a performance or going to harm its chances to qualify to the Grand Final, and in turn towards winning the Song Contest. Meanwhile, delegation members sit in the viewing room and negotiate with the production team over the same camera work as the press. Delegations are looking to have the best three minutes possible, while the production team are looking to make every performance in the show unique with little visual repetition.

Does the camera work really make a difference, and can the viewers even notice that a tool like CuePilot is in use?

Along with my colleague Alexander Åblad, I study Media Technology at KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, and we’ve tried to answer this question in our study ‘Spirit in the Screen: The effect of CuePilot on the viewer’s experience in live broadcasted music competitions.‘ I’ve spent ten years writing about the Song Contest, I’ve also been working with Swedish broadcaster SVT; and have been involved with the production of the Eurovision preview event ‘Israel Calling’ and Eurovision 2019 in Tel Aviv. Alexander has grown up watching the Contest and the National Selections, and also worked with lighting and camera production in church environments.

Alexander (l) and Gil (r) at work. (Photos: Emanuel Stenberg, Private)

Our hypothesis was that pre-programmed camera work will result in a more unified experience among the viewers. A unified experience means that in terms of emotions and their intensities, each individual among a group of viewers would feel the same as the other group members. This can be measured and later analyzed using statistical methods.

Method

Most Eurovision productions will start using CuePilot very early in the process to help plan the camera work with the staging concepts and initial designs, before taking to the actual stage and running rehearsals. It was therefore difficult to find material where the use of CuePilot is the only difference to allow for a comparison.

However, Latvia’s Supernova 2017 was different, CuePilot was only used in the televised Final. As the competition had three stages (2 heats, 1 Semi Final, and the Final), it meant that each of the four finalists had performed twice without CuePilot.

A side-by-side comparison of Triana Park’s “Line” performed during the second heat (without CuePilot) and the final (with CuePilot).

For the research, we used the Semi Final and Final performances of each entry. A total of six different combinations of the four entries were made. Each variant includes two entries with CuePilot and two entries without. The four entries were presented to the participants in the same running order in which they performed in the Supernova 2017 final:

- ‘Your Breath‘, by Santa Daņeļeviča.

- ‘I’m In Love With You‘, by The Ludvig.

- ‘All I Know‘, by My Radiant You.

- ‘Line’, by Triana Park.

Triana Park at Supernova (Latvia 2017)

A total of 30 Media Technology students aged 19 to 31 from KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, Sweden participated in the research. Out of them, 18 identified themselves as females, 11 as male and one as other. Each received a video file featuring one of the six variants and was asked to watch it using their own computers and monitors, with their own headphones, at a quiet location of their choice.

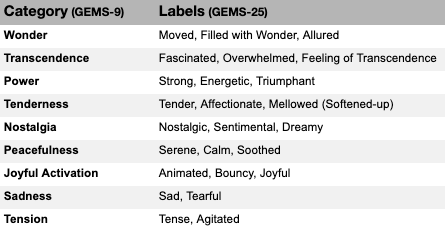

In order to measure the evoked emotions the Geneva Emotional Music Scale (GEMS) was used, a special instrument which was developed exactly for this kind of studies. GEMS includes a set of 45 labels that describe a wide range of emotions and states that can be evoked by listening to music. A shorter scale of 25 labels also exists and is preferred by most users due to the favorable balance between brevity and validity. The labels are grouped into nine different categories (GEMS-9).

GEMS Categories and Labels

After watching each of the four entries, the participants were asked to rate the intensity with which they felt each of the nine categories – not a description of what the entry should mediate but their pure personal feelings – on a five point Likert scale (1: not at all; 2: somewhat; 3: moderately; 4: quite a lot; 5: very much) and had an optional place for leaving short-text comments explaining their ratings.

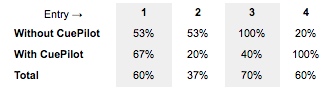

At the end, the participants were introduced to CuePilot and its purpose. The participants had then to determine which two of the four performances they watched had CuePilot in use and to explain their choices. This was asked in order to understand if the use of CuePilot is noticeable among viewers.

Results

GEMS

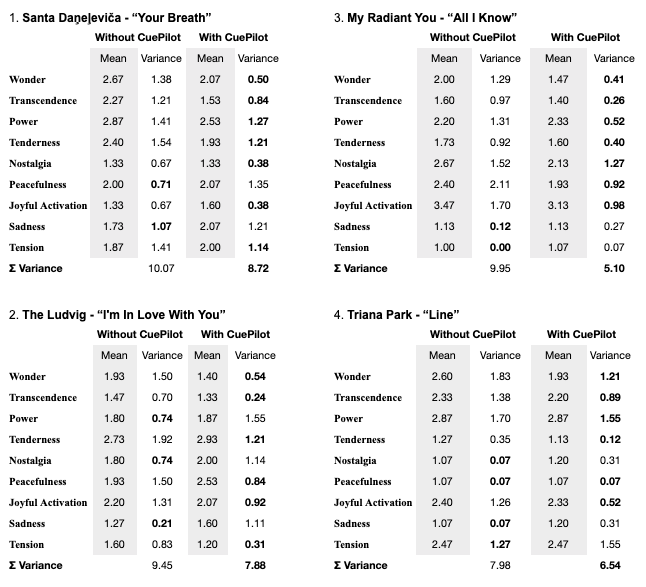

Each of the nine GEMS-categories in each performance was ranked on a scale from 1 to 5 for a total of 15 times each, as each performance was watched by half of the participants. The mean value and the variance were then calculated for each feeling, summed for each performance, and compared between the two variants of each entry (without CuePilot or with CuePilot). These are shown for each entry in the following tables. In each of these tables, the variance value in bold indicates the lowest variance for that specific category among the two versions of the entry, and thus a more unified experience among the group of viewers.

Manual vs CuePilot comparisons

Although the sum of the variances for all entries is smaller for the performance that was directed with CuePilot, a significance test was conducted in order to ensure that the outcome of the experiment did not happen by chance.

Using F-Test for equality of two variances, the question “Is the variance between the means of the two versions significantly different?” was answered for each feeling in each entry. Our null hypothesis assumes that the variances are equal and our alternate hypothesis is that the variances are unequal.

The output of the F-Test is a numerical value. Two equal variances would give us a value of 1.00, like the value of Peacefulness in “Line”. That value gets bigger as the variances are more unequal. In order to assume that the variances are significantly unequal, a desired outcome in our test was getting a result bigger than 2.48, with a sub-condition that the version with CuePilot has the smaller variance. The F-Value of Tension for “All I Know” could not be calculated as a division by zero occurs.

F Values for CuePilot Study

Categories in blue had the smallest variance in version with CuePilot, while the categories in red had the smallest variance without. Categories in bold have a value of more than 2.48 and thus passing the significant test, however in some cases it was the opposite result that was achieved.

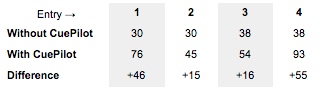

Amount of Shots and CuePilot identification

How many shots were added to each entry with the introduction of CuePilot? Going through the CuePilot scripts of the Final performances and comparing them to the Semi Final performances showed that Entry 4 saw the biggest increase in the number of shots followed by entries 1, 3 and 2 in that order.

Shot Count (CuePilot Study)

The two entries that saw the biggest increase in the number of shots were songs that had electronic music as a characteristic (‘Your Breath‘ and ‘Line‘). The same ranking applies to the successful identification rates of the version directed with CuePilot. A majority (80 percent) of the participants managed to guess only one entry correct. Apart from arbitrary explanations (“I’m not sure, but I felt like, they had a bit of ‘cooler’ camerawork, especially the last one”), more than half of the participants managed to explain their choices in technical terms:

“In ‘Your Breath‘ there are ‘special effects’ at some parts when turning from one camera/angle to another, for example the clouds that ‘blur’ out to another picture, which is most likely pre-programmed” (guessed ‘Your Breath‘ correctly but not ‘Line‘).

“They felt more staged. At one point in ‘Line‘, she was waiting for the camera, which I reacted to. Overall, those two entries felt more complex” (guessed ‘All I Know’ and ‘Line‘ correctly).

The overall identification rates per entry were as follows:

Identification Rates (Cue Pilot Study)

Conclusions

The conclusions drawn from the research is that pre-programmed camera work can result in a more unified experience compared to manual camera work. The ability to do that depends on the overall creativity value of the production, which in turn depends on various aspects such as the number of cameras and the available shooting angles, the production team’s proficiency in using tools as CuePilot, and in the time that the team got to spend on the production.

As seen in Australia Decides’ and Supernova, the use of CuePilot increases the expressive potential of the production while reducing the time needed for reaching a specific production level. Adding more cameras and having a skilled production team will increase the creativity value even more, thus allowing the creation of more unified experiences.

Though not enough significant results were received to conclude CuePilot’s effect on the viewer’s experience, there was a overall tendency of the usage of CuePilot resulting in a more unified experience, which is why further research is encouraged, for example testing two different CuePilot scripts for the same performance or having a bigger and varied test group which is not limited to Swedish university students.

Regarding the subproblem, whether pre-programmed camera work is distinguishable, the conclusion is that it is more noticeable if the performance has quick cuts, special video effects or explicit interaction of the artist with the camera. It is based on the participants’ explanations provided when they choose which two of the entries they watched were directed with CuePilot. These aspects are not unique to pre-programmed camera work but are easier to implement with such tools.

The most significant result in terms of difference between sum of variances, significance tests and overall identification of CuePilot was achieved with ‘All I Know‘ although not having the most radical changes in production. Just adding more shots, quick cuts and video effects will not directly lead to a significant more unified experience among the viewers.

So whether you’re watching the Eurovision Song Contest or making it happen from behind the scenes – know that the camera work can affect the way you feel about a specific performance. Interested in reading the full study? Find it here.

Citations

- Laufer, Gil & Åblad, Alexander. (2020). Spirit in the Screen: The effect of CuePilot on the viewer’s experience in live broadcasted music competitions. 10.13140/RG.2.2.19169.33121.